Come si evince da notizie del sito della Rivista Italiana Difesa, nel corso dell’ultima riunione del Consiglio franco-tedesco di Difesa e Sicurezza, la Cancelliera tedesca Angela Merkel ha ribadito alle controparti francese e spagnola una pressante richiesta degli industriali tedeschi che chiedono a gran voce un ruolo più assertivo all’interno del programma aeronautico SCAF/FCAS di sesta generazione. E' oramai chiaro che l'industria aeronautica tedesca non sopporta la supponenza di Dassault Aviation e chiede un maggior carico tecnologico per il gruppo Airbus.

I tedeschi, dopo l’esperienza nel progetto europeo Eurofighter, preferirebbero apportare e ricevere qualcosa dalle conoscenze sviluppate per il programma; gli industriali tedeschi vorrebbero un trattamento simile per il nuovo SCAF/FCAS. Da quanto è dato comprendere, la controparte francese vorrebbe conservare una posizione leader e mantenere l’esclusività su una parte delle riservatissime tecnologie di un velivolo di 6^ generazione.

Tale posizione non si concilia con la ripartizione a tre degli stanziamenti che, da qui al 2025-2026, ammontano a circa 6 miliardi di €. Il dibattito franco-tedesco riguarderebbe anche il futuro carro franco-tedesco. Il vero nodo gordiano di ambedue i programmi è il Bundestag tedesco, che deve dare il proprio consenso per l’erogazione dei fondi e che lo farà soltanto se riterrà che l’interesse tedesco sarà sufficientemente rispettato.

Future Combat Air System, o FCAS

Il “Future Combat Air System, abbreviato FCAS”, è un progetto tedesco-francese-spagnolo per lo sviluppo di un sistema di caccia multiruolo di VI generazione (New Generation Fighter), anche a pilotaggio remoto (Remote Carrier) e con nuovi sistema d'arma e di comunicazione. Per la parte tedesca, entrerà in servizio con la Luftwaffe nel 2040 sostituendo l'Eurofighter Typhoon, per la parte francese sostituirà nell'Armée de l'air il Dassault Rafale, per la parte spagnola nel Ejército del Aire, sostituirà il McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet oltre che il Typhoon. Le società coinvolte sono la francese Dassault Aviation e la tedesca Airbus Defence and Space. La prima ragione per lanciare il programma FCAS è quella di soddisfare il bisogno di capacità delle forze aeree francesi, tedesche e spagnole nel 2040.

I tre paesi condividono una necessità relativamente coincidente di rinnovare il loro equipaggiamento di aerei da combattimento:

per la Francia, la necessità di trovare un successore del Rafale, in servizio nella Marina dal 1998/99 e nell'Aeronautica dal 2006, e che dovrebbe essere ritirato intorno al 2060. Il FCAS sgraverà progressivamente il Rafale F3R,1 qualificato dalla DGA nel luglio 2018, poi il prossimo Rafale F4, che migliorerà la connettività dell'aereo, le capacità di guerra elettronica e l'efficacia del radar, costituendo un primo passo verso il FCAS. Il FCAS deve anche essere in grado di svolgere la missione di dissuasione nucleare.

per la Germania, la necessità di pianificare un successore dell'Eurofighter, in servizio nella Luftwaffe dal 2004 e che dovrebbe essere ritirato più o meno nello stesso periodo del Rafale, dopo essere stato migliorato nel frattempo. Il nuovo sistema dovrebbe permettere alla Germania di continuare a compiere le sue missioni nucleari per la NATO (bombe a gravità B61 trasportate da P200 Tornado).

per la Spagna, sostituire l'Eurofighter, che è stato ordinato nel 2010, 2014 e 2017. Si noti che l'F/A-18A Hornet dell'ALA 46 spagnolo, basato nelle Isole Canarie e preso dalle scorte statunitensi negli anni '80, scadrà nel 2025. Più tardi, sarà lo stesso per i sessanta aerei dello stesso tipo acquisiti dalla forza aerea spagnola. La marina spagnola utilizza anche una dozzina di AV-8 Harrier II sulla portaerei Juan Carlos I. Per soddisfare le sue esigenze di rinnovamento, la Spagna potrebbe essere tentata di acquisire alcuni F35B, l'unico aereo sul mercato che può decollare verticalmente dalla portaerei. Tuttavia, finora, questa soluzione non è stata adottata a causa della "preferenza europea" della Spagna da un lato e del costo molto elevato degli F35B dall'altro. Anche se si scegliesse l'F35B, non sarebbe senza dubbio una scelta che volge definitivamente la Spagna a favore del costruttore americano.

Il nuovo sistema di armi aeree che succederà al Rafale e all'Eurofighter deve essere un sistema con ruoli multipli2, adatto al contesto del 2040 e dei decenni successivi fino al suo ritiro, probabilmente intorno al 2080. L'opinione generale è che questo contesto sarà caratterizzato da una maggiore contestazione dello spazio aereo da parte degli avversari attraverso strategie "Anti-Access/Area Denial" (A2/AD) attuate con sistemi di rilevamento molto efficaci (radar a banda larga) e sistemi antimissile (come l'S400 russo e i suoi successori). Questo si tradurrà in un rischio di impossibilità di penetrazione nelle aree nemiche, anche se il controllo della terza dimensione rimane essenziale per qualsiasi azione militare, anche a terra.

Inoltre, il nuovo aereo da combattimento dovrà essere in grado di trasportare sia le armi nucleari francesi che quelle della NATO utilizzate dalla Germania, il che avrà un impatto sulle sue caratteristiche ancora da determinare.

Conseguenze per la futura portaerei francese

Le dimensioni e il peso del nuovo aereo da combattimento avranno conseguenze sulle dimensioni di qualsiasi futura portaerei francese e sulle dimensioni dei missili che potranno essere utilizzati e sviluppati in futuro.

Attualmente, il Rafale Marine ha un'apertura alare di 10,90 metri, una lunghezza di 15,27 metri, un peso a vuoto di 10 tonnellate e un peso massimo di 24 tonnellate con le armi. L'NGF sarà più pesante per almeno tre ragioni: deve poter trasportare più effettori, avere una maggiore autonomia di volo, e il suo stealth richiederà senza dubbio una stiva di una certa dimensione per i missili.

Per fare un confronto, il caccia stealth americano F22 Raptor ha un'apertura alare di 13,56 metri, è lungo 18,9 metri, pesa 20 tonnellate a vuoto e fino a 35 tonnellate con tutto il suo carico. Il modello NGF presentato a Le Bourget era lungo 18 metri. L'ammiraglio Christophe Prazuck, capo di stato maggiore della marina francese, ha anche parlato di un peso di circa 30 tonnellate per l'NGF e di dimensioni superiori al Rafale in un'audizione al Senato il 23 ottobre 2019, implicando una portaerei molto più grande e pesante della Charles de Gaulle. Quindi, l'ordine di grandezza considerato sarebbe di 70.000 tonnellate per una portaerei lunga da 280 a 300 metri, rispetto alle 42.000 tonnellate e ai 261 metri dell'attuale portaerei.

Mantenere un aereo "sovrano", mantenendo le competenze d’avanguardia

Se lo sviluppo dell'aereo non viene lanciato ora, Francia e Germania dovranno senza dubbio adottare una soluzione non sovrana nel 2040. Sarà probabilmente l'F35, che dovrebbe rimanere in attività fino al 2080 circa, o uno dei suoi successori americani.

La Francia rinuncerebbe allora alla sua autonomia strategica. Rinuncerebbe anche a una parte della sua base tecnologica e industriale di difesa. Ricordiamo che la Francia è uno dei tre paesi, insieme agli Stati Uniti e alla Russia, che può fabbricare un intero aereo da combattimento.

Sarebbe lo stesso per la Germania. Nonostante il suo atteggiamento tradizionalmente più favorevole nei confronti degli Stati Uniti in materia, la Germania ha deciso nell'aprile 2020 di acquistare 93 Eurofighter (BAE systems, Airbus e Leonardo) e 45 aerei da combattimento americani F-18 (Boeing) per rinnovare la sua flotta di Tornado in grado di trasportare la bomba nucleare americana e non gli F35 come gli americani incoraggiavano, sostenendo che solo un aereo Usa poteva portare questa bomba (anche se il Tornado, attuale vettore all'interno delle forze tedesche, è effettivamente un aereo europeo).

Inoltre, l'abbandono dell'autonomia strategica che deriverebbe dalla mancanza o dal ritardato lancio di un nuovo sistema di combattimento aereo sarebbe senza dubbio permanente. Sarebbe molto difficile per i produttori europei, in particolare i produttori di aerei e motori, saltare una generazione di aerei. Le competenze d'avanguardia necessarie in questo campo possono essere mantenute solo partecipando efficacemente ai programmi industriali. In particolare, per i due principali costruttori francesi che partecipano al progetto NGF3: Dassault e Safran; l'ultimo programma militare risale al Rafale negli anni '80.

Il costruttore francese di aerei non ha più sviluppato un nuovo aereo da combattimento da questo periodo, così come il costruttore di motori non ha più realizzato un motore completo (parti calde e fredde) dall'M88 del Rafale. Pertanto, è urgente che questi due produttori lavorino su un nuovo progetto di grande scala che mobiliti tutte le competenze necessarie per realizzare un aereo completo.

I rappresentanti di Safran e Dassault, considerano il FCAS, come un nuovo programma per un sistema di combattimento aereo e un progetto esistenziale. È questo carattere esistenziale per l'autonomia strategica dell'Europa che, in definitiva, giustifica pienamente il fatto di non soddisfare la necessità con un aereo acquistato "off-the-shelf".

Inoltre, bisogna notare che, in termini di aerei da combattimento, la tendenza internazionale è verso programmi sovrani.

Molte potenze regionali hanno deciso di sviluppare i propri aerei da combattimento, soprattutto in Asia, per sostenere la loro sovranità e sviluppare una rete di produzione locale:

- È il caso della Cina con il Chengdu J-20, un bimotore stealth,

- della Corea del Sud, che sviluppa un aereo da combattimento in collaborazione con l'Indonesia,

- il KF-X, dell'India, che sviluppa l'HAL AMCA tramite il produttore nazionale Hindustan Aeronautics,

- del Giappone, che sviluppa anch'esso l’aereo stealth F3 (non potendo acquisire gli F22 che gli americani hanno rifiutato di esportare),

- della Turchia

- e dell'Iran.

L'attaccamento dei paesi membri del FCAS alla loro autonomia strategica è quindi ampiamente condiviso.

L’APPARATO PROPULSIVO

Questo jet da combattimento di sesta generazione dovrà essere in grado di produrre una forte spinta supersonica e di navigare a bassa velocità per lunghi periodi. Il motore dovrà quindi essere versatile, più compatto e più leggero; la spinta molto più potente di quella del Rafale consentirà al FCAS di trasportare più armamenti.

Si prevede che la turbina possa raggiungere temperature di circa 2.100 K (1.825° C), il che non è attualmente possibile con i materiali e le tecnologie esistenti. Per superare questo problema, la Safran ha fornito una piattaforma di ricerca per sviluppare tecnologie e materiali sofisticati in grado di resistere a queste temperature.

Il FCAS europeo sarà spinto da due motori, sviluppati da Safran e da MTU Aero Engines. Il motore utilizzerà un ciclo variabile: in altre parole, dovrà essere in grado di regolare il rapporto tra i flussi d'aria primaria e secondaria utilizzando un ugello regolabile per rendere l'aereo più facile da manovrare.

Un'altra area di innovazione che verrà esplorata riguarda la creazione di un motore ibrido per gestire i problemi energetici a bordo e gli eventuali armamenti ad energia diretta (laser).

Coloro che sono coinvolti nel FCAS sperano di iniziare i test di volo entro il 2026. Tuttavia, la Safran afferma che il suo motore dimostrativo sarà pronto solo per il 2027 e i primi test di volo del FCAS dovranno utilizzare un motore derivato dall'M88, il propulsore del Dassault Rafale. La Safran è stata incaricata di condurre un programma di ricerca di cinque anni per aumentare la spinta del motore M88, migliorandone al contempo la durata; ciò andrà a beneficio anche del Rafale, utilizzato anche per sviluppare il futuro FCAS.

UN PROGETTO PER APPROFONDIRE LA COOPERAZIONE FRANCO-TEDESCA

Oltre al suo ruolo di progetto di capacità e operazioni, il FCAS è innanzitutto un progetto politico franco-tedesco voluto dal presidente francese e annunciato durante il Consiglio franco-tedesco di difesa e sicurezza del 13 luglio 2017. Esso è un'opportunità per rafforzare e alimentare il partenariato franco-tedesco nell'ambito della volontà di rivitalizzare questa relazione. Sebbene il progetto includa ora la Spagna e possa essere raggiunto da altri paesi, è stato prima il prodotto degli sforzi di Francia e Germania verso la cooperazione negli ultimi anni, in particolare in termini di difesa. Impegnando i due paesi in un partenariato destinato a durare più di 20 anni (e addirittura 50 anni se si aggiunge la durata probabile dei sistemi d'arma), il programma FCAS assicura discussioni molto fitte per tutto questo periodo a livello politico e industriale, così come il futuro progetto di carro armato da combattimento MGCS per i programmi terrestri.

Più di mezzo secolo dopo la firma del trattato dell'Eliseo in segno di riconciliazione (22 gennaio 1963), la firma del trattato di cooperazione e integrazione franco-tedesca da parte del presidente Emmanuel Macron e della cancelliera Angela Merkel il 22 gennaio 2019 ad Aquisgrana ha confermato la volontà dei due paesi di approfondire il partenariato franco-tedesco. In particolare, il capitolo 2 del trattato è intitolato "Pace, sicurezza e sviluppo" e afferma la necessità di rafforzare le relazioni bilaterali di difesa franco-tedesche al fine di creare un'Europa più forte alla luce delle nuove minacce e turbolenze internazionali (Brexit, terrorismo, l'ascesa del populismo, la messa in discussione dell'ordine multilaterale da parte delle potenze mondiali, ecc).

Questo capitolo comprende anche una clausola di assistenza reciproca che prevede anche lo sviluppo di una cultura strategica comune che mira a rafforzare la cooperazione operativa franco-tedesca attraverso schieramenti congiunti, che ricorda l'Iniziativa europea d'intervento e conferma la volontà della Germania di giocare un ruolo più importante sulla scena internazionale.

In termini di capacità e di cooperazione industriale, le due parti di questo trattato si impegnano a intensificare lo sviluppo di programmi comuni di difesa e la loro estensione ai partner e sviluppare un approccio comune anche in termini di esportazioni di armi per questi progetti.

Il trattato di Aquisgrana riafferma il ruolo del Consiglio franco-tedesco di difesa e di sicurezza come organo politico per guidare questi impegni reciproci. Copresieduto dal presidente francese e dal cancelliere tedesco, il CFADS riunisce i ministri degli esteri e della difesa dei due paesi.

Prospettive di rafforzamento della cooperazione operativa franco-tedesca

Il progetto FCAS è nato in un contesto di nuove prospettive di cooperazione operativa tra Francia e Germania. Il trattato di Aquisgrana conferma molti dei progressi visti negli ultimi anni in questo campo. La volontà di agire congiuntamente "ogni volta che sia possibile... in vista del mantenimento della pace e della sicurezza". Mostra la volontà di rafforzare la tendenza vista negli ultimi anni dei dispiegamenti tedeschi nelle zone d'interesse francesi (Sahel e Levante). Sembra anche essenziale lavorare per capitalizzare il maggiore impegno della Germania in questi teatri, in particolare nel Sahel, dove il sostegno tedesco potrebbe essere aumentato se venissero rimosse alcune o tutte le capacità degli Stati Uniti (rifornimento aria-aria, trasporto tattico e strategico, intelligence).

Storia

Nel 2014 iniziò il progetto Future Combat Air System ad opera della Francia e della Gran Bretagna. Più tardi con la presentazione del progetto Tempest della Royal Air Force al Farnborough Air Show il 16 luglio 2018, la parte britannica si ritirò.

Il 13 luglio 2017 la cancelliera Angela Merkel e il presidente Emmanuel Macron siglarono un accordo per lo sviluppo di un caccia in comune. Durante la Mostra internazionale dell'aeronautica e dello spazio di Berlino 2018, il 25 aprile la Dassault Aviation e la Airbus Defence and Space firmano un accordo. Il 26 aprile 2018 il Generalleutnant Erhard Bühler e il Général d'armée aérienne André Lanata presentano all'ILA lo High Level Common Operational Requirements Document. La Francia dovrebbe guidare lo sviluppo del progetto. Anche il Belgio partecipa al programma con 369 milioni di €.

Il ministro della difesa tedesco Ursula von der Leyen e il francese Florence Parly il 6 febbraio 2019 a Gennevilliers dotarono di 65 milioni di € la Dassault Aviation e Airbus per uno studio di due anni. Venne poi posta in essere la collaborazione tra Safran Aircraft Engines e la MTU Aero Engines per lo sviluppo di motori a reazione con cui equipaggiare il nuovo velivolo.

Il nuovo sistema di combattimento, noto in Francia come Système de Combat Aérien Futur (SCAF) e in inglese come Future Combat Air System (FCAS), ed è stato assegnato dall'agenzia di approvvigionamento della difesa francese, DGA, che agisce su per conto di entrambi i governi, ad Airbus e Dassault come co-appaltatori. Il suo costo di 65 milioni di € era suddiviso inizialmente tra i due paesi su base 50-50: la Francia guiderà il progetto New-Generation Fighter così come il Next-Generation Weapon System di cui è un componente, con Dassault come leader industriale e Airbus come partner.

Airbus è responsabile del Future Combat Air System, che integrerà l'NGWS con altre risorse aeronautiche e spaziali interconnesse.

In cambio, la Germania guiderà il progetto del drone europeo MALE e il Maritime Patrol Systems 2030 (entrambi con Airbus come leader del settore) e il Future Ground Combat System bilaterale, con Rheinmetall o KNDS come leader del settore, che alla fine sostituirà sia il Leopard 2 della Germania che

Architettura generale dello SCAF / FCAS

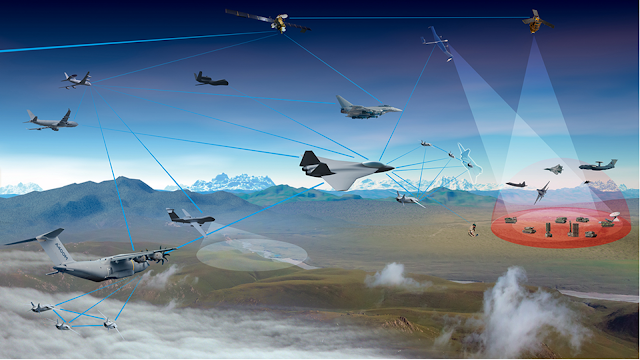

Da quando il programma è stato confermato, l'architettura generale non è cambiata molto: Dassault, con Airbus D&S come suo partner minore, guiderà il programma Next Generation Weapon System e il suo componente principale, il caccia di nuova generazione (NGF) che svilupperà, insieme al suo ambiente di supporto immediato comprendente gregari senza pilota, caccia tradizionali come Rafale ed Eurofighter, aerei rifornitori, AEW etc.…

Come noto, la Francia guida anche lo sviluppo dei motori del caccia di nuova generazione con Safran Military Engines e con la tedesca MTU Aero Engines come partner minore.

Airbus DS, d'altra parte, assumerà la guida per la rete di sensori e sistemi in cui sarà integrato NGWS - il Future Combat Air System - e che è immaginato come rete integrata di risorse spaziali, velivoli con e senza pilota, missili e altre risorse ISR ed EW gestiscono la guerra aerospaziale.

Resta ancora molto da decidere in merito a quali attività verranno combinate nello SCAF / FCAS: la definizione delle loro missioni e quindi i loro requisiti tecnici, nonché chi li progetterà e produrrà. Questi sistemi spaziano dai missili ai satelliti, ai radar terrestri ad altri sensori, all'elaborazione di ordini di battaglia tattici e strategici e alla loro fusione in un quadro operativo comune. Anche questo aspetto del lavoro di sviluppo sarà guidato da Airbus. Il 14 febbraio 2019 anche la Spagna è entrata nel programma.

Obiettivi dell’ambizioso progetto di aerei e sistemi

Il sistema è concepito per integrare droni, aerei da caccia, satelliti artificiali e sistemi di comando e controllo.

Il Système de Combat Aérien du Futur (SCAF)/Future Combat Air System (FCAS) ha cominciato il suo lungo percorso di gestazione con la firma del contratto iniziale da 155 milioni di € che coprirà 18 mesi di studio, per la prima fase del programma di dimostrazione. Ma l’industria francese, la Direction Générale de l’Armement (DGA) e le Forze Armate hanno ben chiaro il percorso evolutivo che porterà dall’attuale RAFALE al futuro SCAF/FCAS. Parigi ha salutato con sollievo il via libera del comitato del bilancio del Bundestag per lo SCAF/FCAS.

L’ambizioso progetto prevede la sostituzione, all’orizzonte del 2040, del Dassault RAFALE francese e degli Eurofighter TYPHOON tedeschi e spagnoli.

Parigi e Berlino avevano subito concordato un equilibrio per evitare litigi di governance:

- la Francia sarebbe stata Paese guida per lo sviluppo del caccia pilotato, elemento centrale dello SCAF/FCAS,

- la Germania per il nuovo carro (MGCS).

La Francia ha dimostrato più volte impazienza sulle tempistiche, sia per ragioni tecniche che politiche. Le ragioni tecniche sono evidenti. L’Europa non ha sviluppato alcun caccia di quinta generazione mentre gli Stati Uniti finanziano già, con investimenti considerevoli, la sesta generazione.

I Governi dei principali Paesi europei continuano a dimostrare scarso interesse per gli investimenti nel settore militare: oggi pressoché tutti i Paesi europei sono ripiegati su se stessi anche a causa della pandemia da COVID-19.

La Francia di questi anni, tra gilet gialli, riforma del sistema pensionistico e liberalizzazione del settore trasporti, con un debito pubblico che non smette di crescere, non fa certo eccezione. Ciononostante, la DGA e gli industriali francesi hanno trovato il Presidente Emmanuel Macron e il suo esecutivo piuttosto ricettivi alle richieste delle FF.AA. francesi e ben consci delle loro necessità di modernizzazione, cui si aggiungono i temi tecnologici e industriali. Angela Merkel si è dimostrata una convinta sostenitrice del binomio franco-tedesco alla guida dell’Europa, così come della volontà di approfondire i legami industriali nel settore militare. La Germania ha posto non pochi problemi, soprattutto per la necessità continua di far passare tutte le decisioni per il Bundestag, cosa che allunga di molto i tempi e che rischia di affossare interi programmi, tenendo presente anche pudori e ritrosie da parte di ampie fette della politica tedesca. La finestra di opportunità per lanciare i programmi terminerà tra il 2021 e il 2022, ovvero le rispettive date di scadenza dei mandati di Macron e Merkel: la grande sfida del programma binazionale è di poter finanziare la costruzione del dimostratore entro il 2022, per poterlo avere in volo nel 2026.

Come velivolo di sesta generazione sarà dotato di tecnologia stealth, un sistema adattivo (ADVENT), rete di computer, capacità di guerra cibernetica e possibilità di uso di armi ad energia diretta.

ENGLISH

According to news from the Rivista Italiana Difesa website, during the last meeting of the Franco-German Defence and Security Council, German Chancellor Angela Merkel informed her French and Spanish counterparts of the demands of German industrialists: they are clamouring for a more technologically significant role in the SCAF/FCAS programme; the Germans cannot stand the arrogance of Dassault Aviation and are asking for a greater technological load for the Airbus group.

The main issue would be the ownership of the know-how acquired through participation in the Franco-German-Spanish programme.

The Germans, with the experience of the European Eurofighter project, would prefer to contribute and receive something from the knowledge developed for the programme. It is certain that German industrialists would like similar treatment for the new SCAF/FCAS; from what we can understand, the French side would like to retain a leading position and keep exclusivity on part of the highly confidential technologies of a 6th generation aircraft.

This position cannot be reconciled with the three-way division of budgets, which amount to some €6 billion between now and 2025-2026.

The Franco-German debate would also concern the future Franco-German wagon.

As we understand it, the real Gordian knot in both programmes is the German Bundestag, which must give its consent for the funds to be disbursed and will only do so if it believes that the German interest is sufficiently respected.

Future Combat Air System, or FCAS

The Future Combat Air System, or FCAS for short, is a German-French-Spanish project to develop a 6th generation multi-role fighter system (New Generation Fighter), including a Remote Carrier and new weapon and communication systems. On the German side, it will enter into service with the Luftwaffe in 2040, replacing the Eurofighter Typhoon; on the French side, it will replace the Dassault Rafale in the Armée de l'Air; and on the Spanish side, in the Ejército del Aire, it will replace the McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornet as well as the Typhoon. The companies involved are France's Dassault Aviation and Germany's Airbus Defence and Space. The primary reason for launching the FCAS programme is to meet the capability needs of the French, German and Spanish air forces in 2040.

The three countries share a relatively coincidental need to renew their combat aircraft equipment:

for France, the need to find a successor to the Rafale, which has been in service in the Navy since 1998/99 and in the Air Force since 2006, and which should be retired around 2060. FCAS will progressively relieve the Rafale F3R,1 qualified by the DGA in July 2018, then the next Rafale F4, which will improve the aircraft's connectivity, electronic warfare capabilities and radar effectiveness, constituting a first step towards FCAS. FCAS must also be capable of carrying out the nuclear deterrence mission.

for Germany, the need to plan a successor to the Eurofighter, which has been in service with the Luftwaffe since 2004 and is due to be retired around the same time as the Rafale, having been upgraded in the meantime. The new system should allow Germany to continue carrying out its nuclear missions for NATO (B61 gravity bombs carried by P200 Tornados).

for Spain, replace the Eurofighter, which was ordered in 2010, 2014 and 2017. Note that the Spanish ALA 46's F/A-18A Hornet, based in the Canary Islands and taken from US stocks in the 1980s, will expire in 2025. Later, it will be the same for the sixty aircraft of the same type acquired by the Spanish air force. The Spanish navy also uses a dozen AV-8 Harrier IIs on the Juan Carlos I aircraft carrier. To meet its renewal needs, Spain might be tempted to acquire some F35Bs, the only aircraft on the market that can take off vertically from the aircraft carrier. However, so far this solution has not been adopted because of Spain's 'European preference' on the one hand and the very high cost of the F35Bs on the other. Even if the F35B were chosen, it would undoubtedly not be a choice that would definitively turn Spain in favour of the American manufacturer.

The new air weapon system that will succeed the Rafale and Eurofighter must be a system with multiple roles2, suitable for the context of the 2040s and subsequent decades until its retirement, probably around 2080. The general view is that this context will be characterised by increased contestation of airspace by adversaries through "Anti-Access/Area Denial" (A2/AD) strategies implemented with highly effective detection systems (wideband radar) and anti-missile systems (such as the Russian S400 and its successors). This will result in a risk of impossibility of penetration into enemy areas, even though control of the third dimension remains essential for any military action, including on the ground.

In addition, the new fighter aircraft will have to be able to carry both French and NATO nuclear weapons used by Germany, which will have an impact on its characteristics yet to be determined.

Consequences for the future aircraft carrier

The size and weight of the new combat aircraft will have consequences for the size of any future French aircraft carrier and the size of the missiles that can be used and developed in the future.

Currently, the Rafale Marine has a wingspan of 10.90 metres, a length of 15.27 metres, an empty weight of 10 tonnes and a maximum weight of 24 tonnes with weapons. The NGF will be heavier for at least three reasons: it must be able to carry more effectors, have a longer flight range, and its stealth will undoubtedly require a missile hold of some size.

By way of comparison, the American F22 Raptor stealth fighter has a wingspan of 13.56 metres, is 18.9 metres long, weighs 20 tonnes empty and up to 35 tonnes fully loaded. The NGF model presented at Le Bourget was 18 metres long. Admiral Christophe Prazuck, chief of staff of the French Navy, also spoke of a weight of around 30 tonnes for the NGF and a larger size than the Rafale in a Senate hearing on 23 October 2019, implying a much larger and heavier aircraft carrier than the Charles de Gaulle. Thus, the order of magnitude considered would be 70,000 tonnes for a 280 to 300 metre long aircraft carrier, compared to 42,000 tonnes and 261 metres for the current aircraft carrier.

Maintaining a 'sovereign' aircraft while retaining cutting-edge expertise

If aircraft development is not launched now, France and Germany will undoubtedly have to adopt a non-sovereign solution in 2040. This will probably be the F35, which is expected to remain in operation until around 2080, or one of its American successors.

France would then give up its strategic autonomy. It would also give up part of its defence technological and industrial base. Remember that France is one of the three countries, along with the United States and Russia, that can manufacture an entire fighter aircraft.

It would be the same for Germany. Despite its traditionally more favourable attitude towards the United States in this matter, Germany decided in April 2020 to buy 93 Eurofighters (BAE systems, Airbus and Leonardo) and 45 American F-18 fighter planes (Boeing) to renew its fleet of Tornados capable of carrying the American nuclear bomb and not F35s as the Americans encouraged, claiming that only a US plane could carry this bomb (even though the Tornado, the current carrier within the German forces, is indeed a European plane).

Moreover, the loss of strategic autonomy that would result from the lack or delayed launch of a new air combat system would undoubtedly be permanent. It would be very difficult for European manufacturers, particularly aircraft and engine manufacturers, to skip a generation of aircraft. The necessary cutting-edge expertise in this field can only be maintained by participating effectively in industrial programmes. In particular, for the two main French manufacturers involved in the NGF3 project: Dassault and Safran; the last military programme dates back to the Rafale in the 1980s.

The French aircraft manufacturer has not developed a new combat aircraft since this period, just as the engine manufacturer has not produced a complete engine (hot and cold parts) since the Rafale M88. Therefore, there is an urgent need for these two manufacturers to work on a new large-scale project that will mobilise all the expertise needed to make a complete aircraft.

The representatives of Safran and Dassault consider FCAS to be a new programme for an air combat system and an existential project. It is this existential character for Europe's strategic autonomy that ultimately fully justifies not meeting the need with an aircraft purchased 'off-the-shelf'.

Moreover, it should be noted that, in terms of combat aircraft, the international trend is towards sovereign programmes.

Many regional powers have decided to develop their own fighter aircraft, especially in Asia, to support their sovereignty and develop a local production network:

- This is the case of China with the Chengdu J-20, a twin-engine stealth aircraft,

- South Korea, which is developing a fighter aircraft in collaboration with Indonesia,

- the KF-X, of India, which is developing the HAL AMCA through the national manufacturer Hindustan Aeronautics,

- Japan, which is also developing the F3 stealth aircraft (since it cannot acquire the F22s that the Americans have refused to export),

- Turkey

- and Iran.

The FCAS member countries' attachment to their strategic autonomy is thus widely shared.

A PROJECT TO DEEPEN FRANCO-GERMAN COOPERATION

Beyond its role as a capabilities and operations project, the FCAS is first and foremost a Franco-German political project desired by the French President and announced during the Franco-German Defence and Security Council of 13 July 2017. It is an opportunity to strengthen and nurture the Franco-German partnership as part of the desire to revitalise this relationship. Although the project now includes Spain and can be joined by other countries, it was first the product of France and Germany's efforts towards cooperation in recent years, particularly in terms of defence. By committing the two countries to a partnership that is set to last more than 20 years (and even 50 years if the likely lifetime of the weapon systems is added), the FCAS programme ensures very close discussions throughout this period at political and industrial level, as does the future MGCS battle tank project for the land programmes.

More than half a century after the Elysée Treaty was signed as a sign of reconciliation (22 January 1963), the signing of the Franco-German cooperation and integration treaty by President Emmanuel Macron and Chancellor Angela Merkel on 22 January 2019 in Aachen confirmed the two countries' desire to deepen the Franco-German partnership. In particular, chapter 2 of the treaty is entitled "Peace, security and development" and states the need to strengthen bilateral Franco-German defence relations in order to create a stronger Europe in light of new international threats and turbulence (Brexit, terrorism, the rise of populism, the questioning of the multilateral order by world powers, etc.).

This chapter also includes a mutual assistance clause that provides for the development of a common strategic culture aimed at strengthening Franco-German operational cooperation through joint deployments, which is reminiscent of the European Intervention Initiative and confirms Germany's desire to play a more important role on the international stage.

In terms of capabilities and industrial cooperation, the two parties to this treaty undertake to intensify the development of joint defence programmes and their extension to partners, and to develop a common approach also in terms of arms exports for these projects.

The Aachen Treaty reaffirms the role of the Franco-German Defence and Security Council as the political body to guide these mutual commitments. Co-chaired by the French President and the German Chancellor, the CFADS brings together the foreign and defence ministers of the two countries.

Prospects for strengthening Franco-German operational cooperation

The FCAS project was born against a background of new prospects for operational cooperation between France and Germany. The Aachen Treaty confirms much of the progress seen in recent years in this field. The willingness to act jointly 'whenever possible ... with a view to the maintenance of peace and security'. It shows a willingness to reinforce the trend seen in recent years of German deployments in French areas of interest (Sahel and Levant). It also seems essential to work to capitalise on Germany's increased commitment in these theatres, particularly in the Sahel, where German support could be increased if some or all US capabilities (air-to-air refuelling, tactical and strategic transport, intelligence) were removed.

History

In 2014, the Future Combat Air System project by France and Great Britain began. Later with the presentation of the Royal Air Force's Tempest project at the Farnborough Air Show on 16 July 2018, the British side withdrew.

On 13 July 2017, Chancellor Angela Merkel and President Emmanuel Macron signed an agreement to jointly develop a fighter jet. During the 2018 Berlin International Aeronautics and Space Exhibition, Dassault Aviation and Airbus Defence and Space sign an agreement on 25 April. On 26 April 2018, Generalleutnant Erhard Bühler and Général d'armée aérienne André Lanata present the High Level Common Operational Requirements Document to the ILA. France should lead the development of the project. Belgium is also participating in the programme with €369 million.

The German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen and the French Florence Parly on 6 February 2019 in Gennevilliers endowed Dassault Aviation and Airbus with €65 million for a two-year study. A collaboration was then put in place between Safran Aircraft Engines and MTU Aero Engines to develop jet engines with which to equip the new aircraft.

The new combat system, known in France as Système de Combat Aérien Futur (SCAF) and in English as Future Combat Air System (FCAS), and was awarded by the French defence procurement agency, DGA, acting on behalf of both governments, to Airbus and Dassault as co-contractors. Its €65 million cost was initially split between the two countries on a 50-50 basis: France will lead the New-Generation Fighter project as well as the Next-Generation Weapon System of which it is a component, with Dassault as industrial leader and Airbus as partner.

Airbus is responsible for the Future Combat Air System, which will integrate the NGWS with other interconnected aeronautical and space assets.

In return, Germany will lead the European MALE drone project and the Maritime Patrol Systems 2030 (both with Airbus as industry leader) and the bilateral Future Ground Combat System, with Rheinmetall or KNDS as industry leader, which will eventually replace both Germany's Leopard 2 and

Overall architecture of the SCAF / FCAS

Since the programme was confirmed, the overall architecture has not changed much: Dassault, with Airbus D&S as its junior partner, will lead the Next Generation Weapon System programme and its main component, the Next Generation Fighter (NGF) which it will develop, together with its immediate support environment including unmanned wingmen, traditional fighters such as Rafale and Eurofighter, refuelling aircraft, AEW etc....

As is well known, France also leads the development of the engines of the new generation fighter with Safran Military Engines and Germany's MTU Aero Engines as a minor partner.

Airbus DS, on the other hand, will take the lead for the network of sensors and systems in which NGWS - the Future Combat Air System - will be integrated and which is envisioned as an integrated network of space assets, manned and unmanned aircraft, missiles and other ISR and EW assets manage aerospace warfare.

Much remains to be decided about what assets will be combined in SCAF / FCAS: the definition of their missions and thus their technical requirements, as well as who will design and produce them. These systems range from missiles to satellites, ground radars and other sensors, to the processing of tactical and strategic battle orders and their fusion into a common operational framework. This aspect of the development work will also be led by Airbus. On 14 February 2019, Spain also joined the programme.

Objectives of the ambitious aircraft and systems project

The system is designed to integrate drones, fighter aircraft, artificial satellites and command and control systems.

The Système de Combat Aérien du Futur (SCAF)/Future Combat Air System (FCAS) has begun its long gestation period with the signing of the initial €155 million contract that will cover 18 months of study, for the first phase of the demonstration programme. But French industry, the Direction Générale de l'Armement (DGA) and the Armed Forces are clear about the evolutionary path from the current RAFALE to the future SCAF/FCAS. Paris welcomed with relief the green light of the Bundestag Budget Committee for the SCAF/FCAS.

The ambitious project will replace the French Dassault RAFALE and the German and Spanish TYPHOON Eurofighters by 2040.

Paris and Berlin had immediately agreed on a balance to avoid governance disputes:

- France would be the lead country for the development of the piloted fighter, a central element of SCAF/FCAS,

- Germany for the new tank (MGCS).

France has repeatedly shown impatience with the timetable, for both technical and political reasons. The technical reasons are obvious. Europe has not developed any fifth-generation fighters, while the United States is already financing the sixth generation with considerable investment.

The governments of the main European countries continue to show little interest in investing in the military sector: today, almost all European countries are turning in on themselves, partly because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

France in recent years, with its yellow waistcoats, reform of the pension system and liberalisation of the transport sector, and its ever-increasing public debt, is no exception. Nonetheless, the DGA and French industrialists have found President Emmanuel Macron and his executive rather receptive to the demands of the French Armed Forces and well aware of their modernisation needs, to which technological and industrial issues must be added. Angela Merkel has shown herself to be a convinced supporter of the Franco-German duo at the helm of Europe, as well as of the desire to deepen industrial links in the military sector. Germany has posed quite a few problems, especially because of the constant need to pass all decisions through the Bundestag, which takes a long time and risks scuttling entire programmes, bearing in mind the modesty and reluctance of large sections of German politicians. The window of opportunity to launch the programmes will end between 2021 and 2022, i.e. the respective expiry dates of Macron and Merkel's mandates: the great challenge for the bi-national programme is to be able to finance the construction of the demonstrator by 2022, in order to have it in the air in 2026.

As a sixth-generation aircraft, it will be equipped with stealth technology, an adaptive system (ADVENT), a computer network, cyber warfare capabilities and the possibility of using directed energy weapons.

(Web, Google, RID, Wikipedia, You Tube)