Storia del progetto

Il Concorso della Regia Aeronautica del gennaio 1938 per un nuovo bombardiere medio si avviò alla conclusione, quasi un anno dopo, senza vincitori. Gli aerei presentati, anche se genericamente adatti allo scopo, si attirarono le aspre critiche dello Stato Maggiore, per la staticità dei criteri di progettazione e la scarsa attenzione prestata per la finezza aerodinamica e, conseguentemente, per le prestazioni delle macchine. In questa situazione decisero di inserirsi i Cantieri Riuniti dell'Adriatico. Questi, reduci dal successo riscontrato dal CANT Z.1007 (aereo che, realizzato a titolo privato dai CRDA, al di fuori di un concorso, si era subito imposto come superiore a tutti i bombardieri medi italiani contemporanei) presso lo Stato Maggiore, e ancora impegnati nella sua conversione alla motorizzazione radiale, continuarono a lavorare sulla stessa base per tirarne fuori modelli sempre più perfezionati.

La scelta cadde inizialmente sul CANT Z.1015B (versione militarizzata dell'aereo da record, direttamente derivato dallo Z.1007, CANT Z.1015, che volò per la prima volta nel gennaio del 1939). La fama del progettista e i precedenti successi bastarono a farne ordinare trentadue prima ancora che l'aereo avesse lasciato il tavolo da disegno, ma non senza che la Regia Aeronautica avesse richiesto, come condizione irrinunciabile, l'aumento del coefficiente di resistenza strutturale del velivolo. Proprio questo però mise in imbarazzo Zappata, infatti per ottenere l'aumento del coefficiente di resistenza c'erano solo due scelte, o si irrobustiva la struttura, appesantendola e pregiudicando le prestazioni, o si alleggeriva l'aereo di qualche componente non strutturale, ovvero si rinunciava ad uno dei tre motori, pregiudicando le prestazioni.

La quadratura del cerchio sembrò possibile grazie alla disponibilità, giudicata imminente, dei nuovi motori radiali Alfa Romeo 135 RC.34, della classe dei 1500 cv, che, unitamente agli alleggerimenti, riduzioni di superficie alare e affinamenti aerodinamici consentiti dalla formula bimotore, avrebbero potuto consentire al nuovo aereo, designato CANT Z.1018, di raggiungere le prestazioni prospettate dello Z.1015B, pur con un motore in meno (e realizzando oltretutto consistenti economie di costruzione). La Regia Aeronautica si lasciò convincere e, tra il febbraio e l'aprile 1939, sostituì l'ordine di trentadue Z.1015B con altrettanti Z.1018, a condizione che questo avesse le stesse prestazioni prospettate per il trimotore, e che un prototipo volasse entro cinque mesi da allora. Non era un compito facile portare in volo, in cinque mesi, un aereo completamente nuovo, ma i CRDA riuscirono a rispettare la strettissima tabella di marcia e, il 9 ottobre 1939, il prototipo, di costruzione lignea, veniva portato in volo dal comandante Mario Stoppani.

Da quel momento cominciarono i ritardi. I primi vennero causati dai motori Alfa Romeo 135 RC.34, che denunciarono problemi di surriscaldamento e vibrazioni. Il tentativo di farli funzionare a dovere, la decisione di sostituirli con un paio di più tranquilli (ma anche 100 kg l'uno più leggeri) Piaggio P.XII RC.35 Tornado da 1.350 CV, l'attesa dei motori (la cui fornitura era a carico della Regia Aeronautica) e il loro montaggio, richiesero altri 5 mesi, e il prototipo, con la nuova motorizzazione, tornò in volo solo il 9 marzo 1940 per poi essere portato a Guidonia per le prove del Centro Sperimentale della Regia Aeronautica che, per incomprensibili motivi, si protrassero per più di un anno, fino al 25 giugno 1941, dopodiché, per altri nove mesi, si tentarono di rimontare e far funzionare i motori Alfa Romeo pure se questi, nel complesso, davano risultati inferiori ai Piaggio.

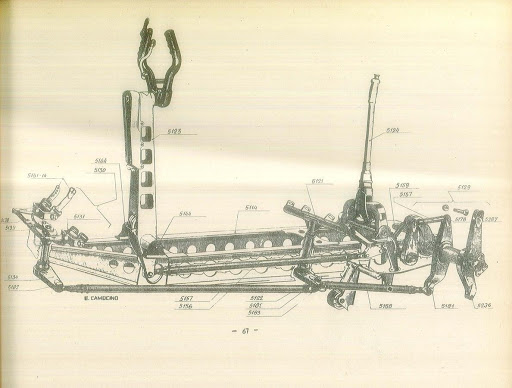

Nel frattempo, nell'ottobre 1940, la commessa per gli Z.1018 metallici era stata portata a 100 aerei, più altri 10 esemplari in legno, simili al prototipo, per consentire un avvio più rapido della produzione, ma da quel momento la Commissione di Allestimento della Regia Aeronautica, come sua consuetudine, sembrò essere più interessata alle modifiche che agli aerei. Un anno e mezzo venne perso per decidere il tipo di impennaggi. Venne richiesta, tra l'altro, la modifica degli armamenti di bordo, l'approntamento di freni aerodinamici per il bombardamento in picchiata, studi per motorizzare l'aereo con ogni sorta di motore aeronautico esistente o solo ipotizzato (tra cui i Daimler-Benz prodotti su licenza, la cui produzione era già insufficiente per i caccia, e l'Isotta Fraschini Sigma, del quale nemmeno un esemplare venne mai assemblato). Intanto i motori veri venivano forniti ai CRDA con il contagocce. Come risultato, il primo CANT Z.1018a (sigla della serie lignea), volò solo il 25 marzo 1942, e l'ultimo venne consegnato alla Regia Aeronautica solo nel giugno 1943. La serie lignea, più che operativamente, venne utilizzata dalla Regia Aeronautica per prove di siluramento, motorizzazione con i più potenti motori Piaggio P.XV RC.15/60 Uragano, da 1.500 CV, ed addestramento degli equipaggi alle nuove macchine.

Sorte non migliore toccò alla serie metallica. Come era da aspettarsi, dati i ritardi nelle decisioni della Commissione di Allestimento e la fornitura a singhiozzo dei motori, lungi dal velocizzare l'avvio della produzione, il fatto che CRDA dovessero lavorare contemporaneamente sugli aerei metallici e lignei contribuì a ritardare le consegne di entrambi. Il prototipo volò per la prima volta il 18 giugno 1942 e venne affidato alla Regia Aeronautica per le valutazioni sperimentali. La Regia Aeronautica aveva inoltre deciso che i primi esemplari di serie facessero da prototipi delle varie varianti previste, quindi i primi aerei consegnati vennero trasformati in: caccia notturno (dotato di un impianto radar Telefunken, e più tardi, accumulando ulteriore ritardo, il radar sperimentale italiano Argo che non entrò mai in produzione, quattro cannoni da 20 mm e quattro mitragliatrici da 12,7 mm in caccia. Era prevista la produzione in serie della versione III, con motori Piaggio P.XV e otto cannoni), silurante (anche con radar di ricerca sperimentale, mai entrato in produzione, Vespa, detto anche "Arghetto", per il siluramento notturno), prova motori con i Fiat A.83 Vortice e Piaggio P.XV R.C. 15/60 Uragano. Alla data dell'armistizio vennero tutti requisiti dai tedeschi, insieme a quattro esemplari completati e non ancora consegnati, a novantacinque esemplari a vari stadi di lavorazione presso gli stabilimenti CRDA e a cento presso quelli Breda (che aveva avuto, a sua volta, una commessa per cento esemplari nel luglio 1941). Il completamento di 28 esemplari venne autorizzato dai tedeschi, ma solo uno riuscì a volare prima che i bombardamenti alleati distruggessero gli impianti. Numerose altre varianti sperimentali (anticarro, caccia notturna, siluranti, bombardiere-ricognitore ad alta quota, assalto, bombardiere a carico e autonomia aumentati ecc.) furono progettate dall'ingegner Zappata, anche presso la Breda (e quindi ebbero denominazione Breda-Zappata BZ 301/304) senza mai volare ma causando ulteriori dispersioni d’energie.

Impiego operativo

Non molto si può dire dell'impiego operativo del CANT Z.1018. Benché alcuni esemplari di Z.1018a siano effettivamente stati consegnati ai reparti operativi prima dell'armistizio, non si è a conoscenza di azioni di guerra effettivamente compiute da questi, ed è più probabile che gli equipaggi si siano limitati a fare attività di addestramento sulle nuove macchine in previsione della distribuzione degli esemplari metallici. Dopo l'armistizio lo Z.1018, nonostante le ottime valutazioni dei collaudatori italiani, e nonostante il fatto che le linee di montaggio sembrassero finalmente essere state approntate, si scontrò con l'ostilità dei comandi tedeschi, che lo consideravano sostanzialmente equivalente allo Junkers Ju 88 e quindi, come questo, non più in grado di sopravvivere alla caccia alleata. La 262ª Squadriglia ricevette 3 esemplari di preserie nel luglio 1943, due dei quali incidentarono in atterraggio. In effetti in tutta la ridda di modifiche e migliorie richieste dalla Regia Aeronautica non si era minimamente pensato all'unico vero difetto del velivolo: la scarsa visibilità del pilota in atterraggio, pericolosa soprattutto per i piloti inesperti (che, dopo 3 anni di guerra, stavano sostituendo quelli ben addestrati degli anni '30). Un altro velivolo di preserie si schiantò, l'8 agosto 1943, in atterraggio, dopo essere stato consegnato ai gruppi di bombardamento radunati a Perugia per essere riarmati, uccidendo l'esperto pilota, Enzo Bravi.

Il più bel bombardiere italiano, quello su cui, secondo i Generali Francesco Pricolo e Rino Corso Fougier (che si successero nel ruolo di Capo di Stato Maggiore dell'Arma Aerea) la Regia Aeronautica aveva puntato tutte le sue speranze per il futuro della sua linea di bombardamento, non riuscì quindi ad avere nessun impatto sulla guerra. La particolare attenzione riservata al progetto sembrò piuttosto avere un effetto deleterio sul suo sviluppo. Tanto che l'aereo che, è da ricordare, aveva volato con quasi un anno di anticipo sui caccia della "serie intermedia", cominciò ad entrare in linea quando questi ne stavano già uscendo, per essere sostituiti dalla successiva generazione di macchine.

Rimane notevole anche perché fu una delle pochissime macchine della Regia Aeronautica su cui fu ipotizzato l'uso di radar, sia per la caccia notturna che per il siluramento e la ricerca navale. Su questo dettaglio era superiore al suo, altrettanto sfortunato, rivale, Caproni Ca.331 Raffica, con cui condivideva la scarsa capacità di far quota rapidamente, fondamentale per un intercettore, poco rilevante per un bombardiere (ed entrambi partivano dalla cellula di un bombardiere veloce).

ENGLISH

CANT Z.1018 Leone was an average Italian Bomber of the Second World War. The project was the work of Filippo Zappata, who conceived it as an improvement on his previous CANT Z.1007 and CANT Z.1015 from which, however, he did not take the three-engine formula. The aircraft, with its slender, clean lines, excellent performance and flight quality, could have been his masterpiece, as well as one of the best average bombers of the war, but, despite the fact that it had been set up well in advance of the outbreak of the war, a succession of delays in its development, due largely to the short-sightedness of the Regia Aeronautica, but also to the unpreparedness of the CANT Z.1007, still engaged in the construction of the CANT Z.1007, to undertake on a large scale the construction of metal structure planes, so that the first mass-produced aircraft reached the flight departments only a few weeks before the armistice.

Project history

The Competition of the Regia Aeronautica in January 1938 for a new medium bomber began to conclude, almost a year later, with no winners. The aircraft presented, although generally suitable for the purpose, attracted the harsh criticism of the General Staff, due to the static design criteria and the lack of attention paid to aerodynamic finesse and, consequently, to the performance of the machines. The Cantieri Riuniti dell'Adriatico decided to join this situation. After the success of the CANT Z.1007 (an aircraft that, privately built by CRDA, outside of a competition, had immediately established itself as superior to all contemporary average Italian bombers) at the General Staff, and still engaged in its conversion to radial engines, they continued to work on the same basis in order to bring out more and more refined models.

The choice fell initially on the CANT Z.1015B (militarised version of the record-breaking aircraft, directly derived from the Z.1007, CANT Z.1015, which flew for the first time in January 1939). The designer's fame and previous successes were enough to order thirty-two of them before the aircraft had even left the drawing board, but not without the Regia Aeronautica requesting, as an essential condition, an increase in the aircraft's structural strength coefficient. This, however, embarrassed Zappata; in fact, in order to obtain the increase in the resistance coefficient, there were only two choices: either the structure was strengthened, weighing it down and compromising performance, or the aircraft was lightened with some non-structural components, or one of the three engines was given up, compromising performance.

The squaring of the circle seemed possible thanks to the availability, considered imminent, of the new Alfa Romeo 135 RC.34 radial engines in the 1500 hp class, which, together with the lightening, reduction in wing area and aerodynamic refinements allowed by the twin-engine formula, could have allowed the new aircraft, designated CANT Z.1018, to achieve the expected performance of the Z.1015B, albeit with one engine less (and achieving substantial savings in construction). Regia Aeronautica was convinced and, between February and April 1939, replaced the order of thirty-two Z.1015Bs with the same number of Z.1018s, provided that this aircraft had the same performance as the three-engine one, and that a prototype would fly within five months from then. It was not an easy task to bring a completely new aircraft into the air in five months, but the CRDA managed to respect the very tight schedule and, on 9 October 1939, the prototype, of wooden construction, was brought into flight by Commander Mario Stoppani.

From that moment on, the delays began. The first delays were caused by Alfa Romeo 135 RC.34 engines, which reported overheating and vibration problems. The attempt to make them run properly, the decision to replace them with a couple of quieter (but also 100 kg each lighter) Piaggio P.XII RC.35 engines Tornado from 1. 350 hp, the wait for the engines (which were supplied by Regia Aeronautica) and their assembly took another 5 months, and the prototype, with the new engine, returned to the air only on 9 March 1940 and was then taken to Guidonia for testing at the Regia Aeronautica Experimental Centre, which was then moved to the new engine, for incomprehensible reasons, they lasted for more than a year, until 25 June 1941, after which, for another nine months, they tried to reassemble and run Alfa Romeo engines even though these, on the whole, were less successful than the Piaggio.

In the meantime, in October 1940, the order for the metallic Z.1018s had been increased to 100 aircraft, plus another 10 wooden ones, similar to the prototype, to allow for a faster start of production, but from that moment on, the Regia Aeronautica's Set-Up Commission, as was its custom, seemed to be more interested in modifications than in aircraft. A year and a half was lost to decide on the type of soaring. Among other things, it was requested the modification of the on-board equipment, the preparation of aerodynamic brakes for nosedive bombardment, studies to motorise the aircraft with all sorts of existing or only hypothetical aeronautical engines (including the Daimler-Benz aircraft produced under licence, whose production was already insufficient for fighters, and the Isotta Fraschini Sigma, of which not even one specimen was ever assembled). Meanwhile, the real engines were supplied to the CRDA with the dropper. As a result, the first CANT Z.1018a (abbreviation of the wooden series), flew only on 25 March 1942, and the last one was delivered to the Regia Aeronautica only in June 1943. The wooden series, more than operationally, was used by Regia Aeronautica for torpedoing tests, engines with the most powerful Piaggio P.XV RC.15/60 Uragano, 1,500 hp, and crew training for the new machines.

No better fate fell to the metal series. As was to be expected, given the delays in the decisions taken by the Set-Up Committee and the hiccup supply of the engines, far from speeding up production start-up, the fact that CRDA had to work simultaneously on the metal and wooden aircraft contributed to delaying deliveries of both. The prototype flew for the first time on 18 June 1942 and was entrusted to the Regia Aeronautica for experimental evaluations. The Regia Aeronautica had also decided that the first series-production aircraft would be prototypes of the various variants envisaged, so the first aircraft delivered were transformed into: night fighters (equipped with a Telefunken radar system, and later, with further delays, the Italian experimental radar Argo, which never entered production, four 20 mm cannons and four 12.7 mm machine guns in the fighter. Series production of the III version was planned, with Piaggio P.XV engines and eight guns), torpedo (also with experimental research radar, never entered production, Vespa, also known as "Arghetto", for night torpedoing), engine test with the Fiat A.83 Vortice and Piaggio P.XV R.C. 15/60 Hurricane. At the date of the armistice, all of them were requisitioned by the Germans, together with four units completed and not yet delivered, ninety-five units at various stages of production at the CRDA plants and one hundred units at the Breda plants (which, in turn, had been ordered one hundred units in July 1941).

The completion of 28 specimens was authorised by the Germans, but only one managed to fly before the Allied bombardments destroyed the plants. Numerous other experimental variants (anti-tank, night fighter, torpedoes, high-altitude bomber-researcher, assault, bombers with increased load and autonomy, etc.) were designed by engineer Zappata, also at Breda (and therefore were named Breda-Zappata BZ 301/304) without ever flying but causing further dispersion of energy.

Operational use

Not much can be said about the operational use of CANT Z.1018. Although some Z.1018a specimens were actually delivered to the operational departments before the armistice, we are not aware of any war actions actually carried out by them, and it is more likely that the crews simply trained on the new machines in anticipation of the distribution of the metal specimens. After the armistice, the Z.1018, in spite of the excellent evaluations of the Italian testers, and in spite of the fact that the assembly lines finally seemed to have been prepared, collided with the hostility of the German commands, which considered it substantially equivalent to the Junkers Ju 88 and therefore, like this one, no longer able to survive the Allied fighters. The 262nd Squadron received 3 pre-series in July 1943, two of which landed. In fact, in all the many modifications and improvements requested by the Regia Aeronautica, no thought had been given to the only real defect of the aircraft: the poor visibility of the pilot during landing, dangerous especially for inexperienced pilots (who, after 3 years of war, were replacing the well-trained pilots of the 1930s). Another pre-production aircraft crashed, on 8 August 1943, while landing, after being handed over to the bombing groups gathered in Perugia to be re-armed, killing the expert pilot, Enzo Bravi.

The most beautiful Italian bomber, the one on whom, according to Generals Francesco Pricolo and Rino Corso Fougier (who succeeded each other in the role of Chief of Staff of the Air Force), the Regia Aeronautica had pinned all its hopes for the future of its bombing line, was therefore unable to have any impact on the war. The special attention paid to the project seemed to have a detrimental effect on its development. So much so that the aircraft, which, it should be remembered, had flown almost a year ahead of the "intermediate series" fighters, began to enter the line when they were already leaving, to be replaced by the next generation of machines.

It remains remarkable also because it was one of the very few machines of the Regia Aeronautica on which the use of radar was hypothesized, both for night fighters and for torpedoing and naval research. On this detail it was superior to its equally unlucky rival, Caproni Ca.331 Raffica, with whom it shared the scarce ability to make altitude quickly, fundamental for an interceptor, not very relevant for a bomber (and both started from the cell of a fast bomber).

(Web, Google, Wikipedia, You Tube)