DAL MISSILE NUCLEARE ITALIANO “ALFA” (1957-1976) AL “VEGA” (1998-2021): una base iniziale per un missile strategico europeo?

Il programma Alfa, lanciato negli anni settanta dall'Italia, verteva su di un Medium-Range Ballistic Missile prodotto dall'Aeritalia e simile al Polaris A-3. Se fosse diventato operativo avrebbe avuto una gittata di oltre 1600 km, armato con una singola testata nucleare da 1 megatone.

Il 28 novembre 1957 i governi francese, italiano e tedesco firmarono un accordo segreto per dotarsi di un deterrente nucleare comune. Tale accordo fu rigettato dal presidente francese Charles de Gaulledopo la sua elezione, in quanto egli decise di dotare la Francia di un proprio arsenale nucleare indipendente. Nei primi anni sessanta l'Italia si trovò circondata da nazioni che stavano perseguendo la costruzione di armi nucleari. La Jugoslavia e Romania avevano iniziato a sviluppare indipendentemente proprie armi atomiche, e collaboravano nella progettazione e nello sviluppo del nuovo cacciabombardiere Soko-IAR J-22 Orao destinato al loro utilizzo. Anche il governo della neutrale Svizzera aveva deciso, in data 23 dicembre 1958, di dotare le proprie forze armate di armi nucleari.

Nel 1957 la Marina Militare aveva iniziato i lavori di trasformazione dell'incrociatore leggero Giuseppe Garibaldi in nave lanciamissili. Durante i lavori di trasformazione eseguiti presso l'Arsenale di La Spezia venne deciso di installare, in una apposita tuga poppiera, quattro pozzi di lancio per missili balistici Polaris dotati di testata nucleare. Tale installazione di armi nucleari su nave di superficie rientrava in concetto operativo NATO di nuova concezione. L'incrociatore lanciamissili Garibaldi rientrò in squadra nel corso del 1961, iniziando le prove di collaudo dei pozzi cui seguirono lanci di collaudo di simulacri inerti e di simulacri autopropulsi, sia con nave ferma che in navigazione. Il primo lancio di un simulacro di missile balistico fu eseguito il 31 agosto 1963 nel golfo di La Spezia. Anche se le prove eseguite diedero tutte esito positivo, i missili non vennero mai forniti dal governo americano, poiché motivi politici ne impedirono la prevista acquisizione. Il 5 gennaio 1963 il governo americano, in base agli accordi successivi alla Crisi dei missili di Cuba raggiunti con l'Unione Sovietica, decise di ritirare i missili balistici a medio raggio PGM-19 Jupiter dal territorio italiano e turco. Tale decisione venne successivamente approvata dal governo italiano, e la 36ª Aerobrigata Interdizione Strategica fu disattivata il 1º aprile 1963 e sciolta ufficialmente il 21 giugno dello stesso anno. In alternativa il governo italiano decise di sviluppare un proprio programma nucleare. Nel dicembre 1964 il generale Paolo Moci decise di chiedere l'autorizzazione all'allora Capo di Stato Maggiore della Difesa, generale Aldo Rossi, per l'avvio della realizzazione di un deterrente nucleare nazionale. Il generale Rossi diede la sua autorizzazione di massima, raccomandando che su tale iniziativa fosse mantenuto il più rigoroso segreto. Il generale Moci ebbe numerosi colloqui con il massimo esperto missilistico italiano dell'epoca, il professor Luigi Broglio, che aveva lanciato numerosi satelliti equatoriali dalla base di Mombasa. Da tali colloqui scaturì, considerate le possibilità economiche della nazione, l'idea di costruire un missile con una gittata di 3000 km, avente quindi la possibilità di colpire tutta l'Europa e l'Africa del nord, armato con una testata nucleare di 2,5 kg di plutonio. La prevista realizzazione di 100 missili avrebbe avuto un costo pari a quello della messa in linea dei nuovi cacciabombardieri Lockheed F-104G Starfighter.

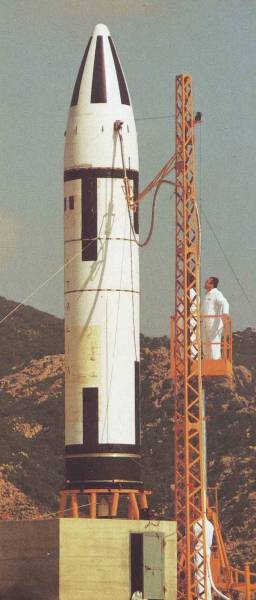

In quel momento il governo statunitense stava dando un'alta priorità alla non proliferazione nucleare, e spingeva per arrivare alla firma di un trattato internazionale. L'Unione Sovietica fece dell'eliminazione della Multilateral Force nucleare NATO una delle condizioni preliminari alla sua adesione al Trattato di non proliferazione nucleare, che fu firmato il 1º luglio 1968 da USA, Regno Unito e Unione Sovietica. Né la Svizzera, né i paesi dei Balcani, né l'Italia lo ratificarono immediatamente. Il governo svizzero aderì al trattato nel 1969, mentre quelli jugoslavo e rumeno lo ratificarono entro il marzo del1970. I servizi di intelligence occidentali indicarono che, anche dopo la firma del trattato, la Jugoslavia stava ancora sviluppando armi nucleari presso l'istituto di Vinca, situato nelle vicinanze di Belgrado. In base a questi rapporti il governo italiano decise di adottare le opportune misure per lo sviluppo di un deterrente nucleare indipendente. Nel 1971 la Marina Militare iniziò lo studio, sotto l'egida del G.R.S. (Gruppo di Realizzazione Speciale Interforze) del C.T.S.D., di un missile balistico a medio raggio di produzione nazionale. Tale missile doveva essere imbarcato su sottomarini e grandi unità di superficie. Il progetto dell'Alfa prevedeva un missile a due stadi a combustibile solido. Per l'impiego imbarcato era previsto il sistema del lancio a freddo, in cui veniva utilizzata la pressione del gas per espellere il missile dal contenitore di lancio. Il primo stadio si accendeva solamente quando il missile era completamente fuori dal contenitore di lancio.

Il primo stadio era lungo 3,845 m, pesava 6 959 kg e utilizzava 6 050 kg di combustibile solido in grani a stella a cinque punte HTPB (composto dal 12% di alluminio, 15% di legante (Binder) e il 73% di perclorato di ammonio) su licenza Rocketdyne. Il motore BPD del primo stadio disponeva di quattro ugelli in fibra di carbonio dotati di giunto cardanico e rivestiti in grafite. Il motore garantiva una spinta al decollo di circa 25 tonnellate (250.00 kN) per 57 secondi. Il secondo stadio pesava 950 kg. Il missile pesava al lancio 10 695 kg, era lungo 6,50 m, ed era dotato di un'autonomia di circa 1 600 chilometri, che scendeva a 1 000 km con l'installazione di una testata bellica del peso di 1 000 kg. La testata comprendeva un singolo veicolo di rientro dotato di testata termonucleare della potenza di 1 megaton. Il sistema di guida inerziale era fornito dalla francese Sagem, e disponeva di una centrale Type E 38 a giroscopi flottanti. Alla realizzazione del programma Alfa contribuirono le principali aziende aerospaziali italiane. Capofila era l'Aeritalia (strutture e scudo termico), mentre la SNIA-BPD Spazio forniva il motore, la Sistel l'elettronica di bordo e la Selenia il sistema di controllo e guida da terra. Altre ditte minori incluse nel programma furono la SNIA-Viscosa Laben-Montedel (centrale di tiro),Mupes (rampa di lancio), e la Motofides/Whitehead. Tra il dicembre 1971 e il luglio 1973 vennero effettuate diverse prove su modelli in scala del propulsore presso lo stabilimento BPD Spazio di Colleferro. Il motore del primo stadio venne collaudato undici volte in prove statiche, tra il dicembre 1973 e il gennaio 1975, preso il balipendio Cottrau della Marina Militare, sito a La Spezia. Il primo lancio sperimentale del missile, dotato del secondo stadio inerte, avvenne dal poligono di Salto di Quirra (Sardegna) alle 17:00 dell'8 settembre 1975. Il missile raggiunse i 25 km in un minuto, arrivando a 110 km di quota, e ricadendo ad una sessantina di chilometri dal Poligono. Ulteriori due missili di prova furono lanciati da Salto di Quirra, il secondo il 23 ottobre 1975, mentre il terzo e ultimo lancio avvenne il 6 aprile 1976. Tutti i lanci furono coronati da successo. Lo sviluppo del sistema d'arma Alfa, costato ormai la cifra di sei miliardi di lire, fu fermato in questa fase, quando il programma nucleare jugoslavo era ormai in fase di abbandono. Sotto la pressione degli Stati Uniti l'Italia firmò il Trattato di non proliferazione nucleare il 2 maggio 1975, mentre la Svizzera ratificò il trattato e concluse definitivamente il suo programma nucleare nel 1977. Il missile Alfa sarebbe stato in grado di trasportare una testata nucleare da una tonnellata ad una distanza di 1600 km, sufficiente a colpire Mosca e altri obiettivi nella Russia europea con lancio dal Mare Adriatico. Il patrimonio tecnologico del programma confluì nei successivi lanciatori spaziali italiani a propellente solido, tra cui l'Advanced Scout e il progetto Vega.

IL MISSILE Vega

Vega, acronimo di Vettore Europeo di Generazione Avanzata, è un vettore operativo in uso dalla Arianespace, sviluppato in collaborazione dall'Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (ASI) e l'Agenzia Spaziale Europea (ESA) per il lancio in orbita di piccoli satelliti (300 – 1500 kg).

Il Vega, che prende il nome dall'omonima stella della costellazione Lyra, è un vettore a corpo unico, senza booster laterali, con tre stadi a propellente solido P80, Zefiro 23, Zefiro 9 e uno stadio per le manovre orbitali a propellente liquido, l'AVUM.

Lo sviluppo tecnico è stato affidato all'italiana ELV, una società partecipata al 70% dall'Avio e al 30% dall'ASI. Il concetto iniziale di partenza del progetto del lanciatore, conosciuto in un primo tempo semplicemente come "Zefiro" dal nome del modello unico di propulsore previsto nella configurazione originaria, era stato presentato dall'allora BPD Difesa Spazio all'ASI, nel 1988, quale successore del vettore Scout (utilizzato dal programma "Progetto San Marco") di cui si prospettava, ormai, una prossima cessazione della produzione. Il progetto definitivo Vega è stato avviato nel 1998 con l'approvazione finale da parte dell'Agenzia Spaziale Europea. L'Italia è il maggior finanziatore e sviluppatore del programma con una quota del 65%, seguono la Francia (12,43%), il Belgio (5,63%), la Spagna (5%), i Paesi Bassi (3,5%) e infine con quote marginali la Svizzera (1,34%) e la Svezia (0,8%).

Il razzo è progettato per il trasporto in orbita di piccoli carichi, tra i 300 e i 1500 kg, in orbite basse o polari, in particolar modo eliosincrone. Una caratteristica particolare e molto apprezzata è la possibilità di trasportare due o tre piccoli carichi contemporaneamente e posizionarli correttamente su orbite diverse, capacità non comune nei lanciatori di così piccole dimensioni.

Il lanciatore è formato da un corpo singolo a quattro stadi, alto circa 30 metri, con un diametro massimo di circa 3 metri e con un peso al decollo di 137 tonnellate. A differenza di molti altri vettori, il Vega è stato costruito in fibra di carbonio.

I 4 STATDI DEL LANCIATORE:

- P80 - Il primo stadio di Vega in ordine di accensione, detto P80 è il più grande e più potente propulsore a propellente solido monoblocco del mondo. Questo programma è stato guidato dal Centre national d'études spatiales (CNES) di Évry ed è stato finanziato da Francia (66%), Belgio, Paesi Bassi e Italia. Oltre a realizzare il primo stadio di Vega, il progetto P80 puntava anche a sviluppare nuove tecnologie utili per i futuri sviluppi della serie Ariane. La progettazione dello stadio è stata affidata all'italiana Avio (motore) e alla italo-francese Europropulsion (integrazione), oltre a commesse minori alla belga SABCA (sistema di controllo), alla francese Snecma (ugello di scarico) e all'olandese Stork B.V. (sistema di accensione). Lo stadio è alto 11,20 metri, ha un diametro di 3 metri e un peso di 96,263 tonnellate, di cui 87,710 di propellente. La spinta prodotta dal motore, equivalente a 3 015 kN, viene fornita per 109,9 secondi. Il P80 è stato sottoposto a due test di accensione, il primo si è svolto a Kourou il 30 novembre 2006 e si è concluso con successo: il motore ha fornito un comportamento molto simile alle previsioni. Lo sviluppo del progetto si è quindi concluso con una seconda prova di accensione a Kourou il 4 dicembre 2007, durante la quale è stato utilizzato un nuovo ugello orientabile. Il motore ha generato una spinta in linea con le aspettative, permettendo allo stadio di essere dichiarato pronto per i voli.

- Zefiro 23 e Zefiro 9 - ZEFIRO = ZEro FIrst stage ROcket motor deriva dalla configurazione originaria del VEGA che prevedeva due Zefiro uguali per i primi due stadi del Lanciatore detti stadio zero e primo stadio. Lo Zefiro 23 e lo Zefiro 9, dove il numero rappresenta il peso in tonnellate previsto all'inizio della progettazione, sono rispettivamente il secondo e il terzo stadio di Vega. Sono stati sviluppati, costruiti e testati da Avio, con la collaborazione della SABCA per il sistema di controllo. Lo Zefiro 23 è stato sottoposto a due prove di accensione presso il poligono del Salto di Quirra, la prima il 26 giugno 2006, la seconda il 27 marzo 2008. Entrambe si sono svolte con successo e lo Zefiro 23 è stato dichiarato abilitato al volo. Anche lo Zefiro 9 è stato sottoposto a due prove di accensione al Salto di Quirra. La prima, svoltasi il 20 dicembre 2005 si è risolta in un pieno successo; al contrario durante la seconda, del 27 marzo 2008, che seguiva un lavoro di revisione sulla base dei dati del primo test, il motore ha mostrato un calo anomalo della pressione interna. L'insuccesso ha provocato un ritardo nello sviluppo del lanciatore, tuttavia il 23 ottobre 2008, in occasione di un nuovo test, il motore ha mostrato prestazioni soddisfacenti, anche grazie ad un nuovo ugello e una maggiore quantità di propellente.

- AVUM - Il quarto stadio, denominato Attitude and Vernier Upper Module, ospita il motore responsabile dell'inserimento finale in orbita del carico. Al contrario degli stadi precedenti, che utilizzano propellente solido, il quarto stadio utilizza un propellente liquido, costituito da dimetilidrazina asimmetrica (UDMH) e tetraossido di diazoto come comburente. La regolazione dell'orientamento del modulo è attuata tramite un sistema che fa uso di idrazina. Al di sopra del sistema propulsivo si trova un modulo che ospita i componenti principali dell'avionica del lanciatore. Lo stadio è alto 2,04 metri, ha un diametro di 2,18 metri e un peso di 1265 chilogrammi, di cui fino a 577 di propellente. La spinta fornita dal motore per 667 secondi equivale a 2,45 kN. Il modulo è di tecnologia e produzione ucraina e spagnola: il motore è sviluppato dall'azienda Yuzhnoye mentre una controllata spagnola di EADS è responsabile della struttura e della scocca. In passato si è discusso riguardo alla possibilità di sostituire il motore ucraino con uno tedesco in modo da rendere il modulo una produzione totale europea.

Copertura del carico

La copertura del carico, il cosiddetto payload fairing, è stato progettato e prodotto dalla svizzera RUAG Space. Ha un diametro di 2,6 metri, un'altezza di 7,88 metri e una massa di 540 kg.

Lanci e test di qualifica

Il 26 giugno 2006 è stata portata a termine, presso il Poligono Sperimentale e di Addestramento Interforze di Quirra (Sardegna), la prova di accensione dei motori del secondo stadio Zefiro 23, che ha permesso di raccogliere fondamentali informazioni sulle caratteristiche dello stadio: variazioni di pressione, temperatura e velocità di combustione, profilo di spinta, controllo dell'orientamento della spinta tramite gli attuatori elettromeccanici che azionano l'ugello. I parametri raccolti hanno decretato il pieno successo della prova. Il 30 novembre 2006 si è svolta con successo presso il centro spaziale della Guyana francese la prova di accensione dei motori del primo stadio P80 del lanciatore. Il 5 dicembre 2007 la versione definitiva del motore P80 è stata collaudata con successo nel centro spaziale di Kourou nella Guiana Francese.

Primo lancio

Il primo volo di Vega, codice volo VV01, inizialmente previsto per il novembre del 2010, è avvenuto il 13 febbraio 2012 dal Centre spatial guyanais di Kourou, portando in orbita nove satelliti, fra cui gli italiani LARES acronimo di LAser Relativity Satellite (satellite ideato per misurare, con una precisione dell'1%, l'effetto Lense-Thirring della relatività generale), costruito con la collaborazione dell'Università La Sapienza, e ALMASat-1, costruito nel polo ingegneristico di Forlì dell'Università di Bologna.

Programma VERTA

Dopo il primo volo l'Agenzia Spaziale Europea aveva previsto cinque lanci, come parte del programma VERTA (VEga Research and Technology Accompaniment) volto a convincere i potenziali utenti della validità del vettore. Durante questi voli, VEGA ha portato in orbita quattro satelliti dell'Agenzia Spaziale Europea: Proba-V (osservazione della Terra), ADM-Aeolus (studio dell'atmosfera), LISA Pathfinder (studio delle onde gravitazionali) e l'Intermediate Experimental Vehicle (IXV). Insieme ai carichi principali sono stati lanciati anche nanosatelliti a scopi didattici come e-st@r del Politecnico di Torino. Il programma VERTA prevedeva una frequenza minima di due lanci per anno, con l'obiettivo di dimostrare le potenzialità di VEGA per lo sfruttamento commerciale e si è concluso con il lancio del dimostratore LISA Pathfinder.

Secondo lancio

Il secondo lancio (primo lancio del programma VERTA), codice volo VV02, è stato effettuato alle 4 (ora italiana) del 7 maggio 2013, trasportando in orbita il satellite Proba-V dell'ESA, in grado di eseguire un rilievo globale della vegetazione, il primo satellite estone, l'ESTCube-1, e un satellite vietnamita il VNREDSAT.

Terzo lancio

Il 30 aprile 2014 alle ore 3.35 (ora italiana) è avvenuto il terzo lancio del vettore, il primo lancio esclusivamente commerciale. Il lancio è avvenuto dalla piattaforma numero 1 del Centre spatial guyanais a Kourou nella Guyana Francese, la stessa usata per i razzi Ariane 1. Con questo lancio si è messo in orbita un satellite, il KazEOSat-1, del peso complessivo di 900 kg che fornirà immagini multispettrali ed in pancromia ad alta risoluzione dell'intero pianeta, che verranno utilizzate per il monitoraggio e la mappatura del pianeta, il supporto alla gestione delle catastrofi naturali e la pura sorveglianza del territorio.

Quarto lancio

Il quarto lancio è avvenuto regolarmente l'11 febbraio 2015 e ha portato in una traiettoria sub-orbitale il veicolo sperimentale europeo IXV. Durante il volo, il quarto stadio AVUM è entrato brevemente in orbita e poi ha eseguito una manovra di de-orbiting come pianificato.

Quinto lancio

Il quinto lancio (il primo del lotto della fornitura Arianespace-ELV) è avvenuto il 23 giugno 2015 alle 3:51 ora italiana dalla base di Kourou per mettere in orbita il satellite Sentinel 2A facente parte del programma europeo Copernicus (messa in orbita di una decina di satelliti). Compito di questo satellite è svelare, per i prossimi 7 anni, i "colori" della terra controllando così lo stato di salute del nostro pianeta, con particolare attenzione alle aree agricole e alle foreste. Il satellite Sentinel 1A è stato lanciato in orbita il 3 aprile 2014 tramite il razzo Soyuz.

Sesto lancio

Il sesto lancio (il quinto ed ultimo del programma VERTA) è avvenuto sempre a Kourou il 3 dicembre 2015 alle 04;04;00 UTC, per mettere in orbita il satellite della Airbus LISA Pathfinder per il quale era stata inizialmente prevista una vita operativa di un anno, in seguito estesa fino al giugno del 2017.

Fornitura Arianespace-ELV

A novembre 2013 è stato firmato un contratto tra Arianespace ed ELV per la fornitura di dieci vettori VEGA, che saranno lanciati nell'arco di tre anni dopo la fine del programma VERTA.

Settimo lancio

Il settimo lancio, avvenuto alle 01:43 UTC del 16 settembre 2016, ha permesso l'immissione in orbita di 4 satelliti della piattaforma di rilevamento della superficie terrestre "Terra Bella" e del satellite di osservazione PeruSAT-1.

Ottavo lancio

Con l'ottavo lancio avvenuto alle ore 13.51 UTC del 5 dicembre 2016 è stato messo in orbita il satellite turco per l’osservazione della terra Gokturk-1.

Nono lancio

Il 7 marzo 2017 alle 01:49 UTC è stato lanciato con successo il satellite Sentinel 2B nell'ambito del progetto europeo Copernicus per il monitoraggio delle terre emerse e delle acque costiere del pianeta.

Decimo lancio

Con il lancio del 2 agosto 2017 sono stati messi in orbita due satelliti per l'osservazione terrestre, l'OPTSAT-3000 per conto del Ministero della difesa italiano e il satellite franco-israeliano VENµS.

Undicesimo lancio

Con la missione VV11 è stato lanciato l'8 novembre del 2017 il satellite Mohammed VI-A per conto del Marocco. Inizialmente era previsto che il carico pagante della missione VV11 fosse il satellite dell'ESA ADM-Aeolus, ma nel corso del 2017 fu deciso di far slittare al 2018 il lancio dell'Aeolus e di assegnare al satellite marocchino l'ultimo lancio del Vega del 2017.

Dodicesimo lancio

Il primo lancio del 2018 del Vega ha visto la messa in orbita del satellite meteorologico ESA ADM-Aeolus per la rilevazione accurata del profilo dei venti. Inizialmente previsto per il 21 agosto, il lancio fu posticipato di un giorno a causa delle avverse condizioni meteo in quota.

Tredicesimo lancio

Il 21 novembre 2018, con la missione VV13, è avvenuto il lancio del secondo satellite Mohammed VI per conto del Marocco. Come l'anno precedente, la natura del carico pagante è rimasta riservata fino a poche settimane prima del lancio. Al suo posto era infatti previsto il satellite PRISMA, poi slittato al marzo 2019.

Quattordicesimo lancio

Nella notte tra il 21 ed il 22 marzo 2019, è stata lanciata la missione PRISMA dell'Agenzia Spaziale Italiana, il primo satellite sviluppato in Europa per l'osservazione iperspettrale della Terra. Grazie ai suoi sensori in grado di rilevare separatamente più di 200 bande nello spettro ultravioletto, visibile ed infrarosso, è possibile acquisire immagini della superficie terrestre contenenti informazioni anche sulla composizione chimico-fisica degli oggetti osservati.

Quindicesimo lancio - Fallimento missione VV15

L'11 luglio 2019 la missione VV15 ha segnato il primo fallimento del lanciatore Vega. A due minuti dal decollo, poco dopo l'accensione del secondo stadio, si è verificata un'anomalia che ha portato alla deviazione dalla traiettoria prevista. La missione si è quindi conclusa con la perdita del carico utile, il satellite militare Falcon Eye 1.

Il rapporto preliminare della Commissione indipendente che ha indagato sulle cause del fallimento della missione, ha stabilito che a 130 secondi dal decollo (T+130), 14 secondi dopo l'accensione del secondo stadio, si è verificato un rapido e violento cedimento strutturale della parte anteriore del motore Zefiro 23 che ha provocato la rottura del lanciatore in due parti. A T+135 la traiettoria ha iniziato a discostarsi da quella nominale e a T+213 è stata comandata da terra l'autodistruzione del vettore. L'ultimo segnale della telemetria è stato ricevuto a T+314. La Commissione ha proposto un piano di verifiche e azioni correttive da completare prima della ripresa della campagna di lanci del Vega, prevista per il primo trimestre 2020.

Successive analisi e test su modelli in scala e a grandezza naturale hanno identificato, riprodotto e confermato che il cedimento strutturale è stato causato da un difetto nell'isolamento termico nella parte superiore del Zefiro 23 che, provocando una fuga di gas ad alta temperatura, ne ha determinato il malfunzionamento.

Sedicesimo lancio - Ritorno in servizio

A più di un anno di distanza dal fallimento della missione VV15, il 3 settembre 2020 è stato completato con successo il sedicesimo lancio del vettore Vega. Con un carico di 53 satelliti di 21 clienti provenienti da 13 diverse nazioni, ha dimostrato la capacità del sistema Ssms (Small Spacecraft Mission Service) di rilasciare micro e nano satelliti in differenti orbite in un'unica missione.

La missione, inizialmente prevista a settembre del 2019, è stata prima rimandata a marzo 2020 in seguito alle verifiche di qualità sul sistema di produzione dettate dall'inchiesta sulla missione precedente e poi, a causa della pandemia di Covid-19, ad agosto 2020. I venti periodici presenti alle latitudini equatoriali, incompatibili con il profilo di missione, hanno però provocato una serie di ritardi nel lancio che è stato riprogrammato per il due settembre. Dopo un ennesimo ritardo dovuto ad un tifone che si stava abbattendo sulla stazione di controllo della telemetria in Corea del Sud, il Vega è stato finalmente lanciato nella notte tra il 2 ed il 3 settembre 2020.

Diciassettesimo lancio - Fallimento missione VV17

Il 17 novembre 2020 si verifica una nuova anomalia durante la missione VV17 che si conclude a soli 8 minuti dal lancio. Dopo un corretto funzionamento del primo, secondo e terzo stadio, si è verificata un’anomalia del quarto stadio che ha provocato una deviazione della traiettoria del lanciatore.

Sviluppi futuri:

- Vega C - Lo sviluppo della versione Vega C è stato formalmente approvato il 12 agosto 2015 e prevede l'impiego di un P120C per il primo stadio (una versione maggiorata del P80, usata anche come booster di Ariane 6), un Z40 al secondo stadio, uno Z9 per il terzo e l'AVUM+ (che ha il 20% di propellente in più rispetto all'AVUM standard) per il quarto stadio. Questa versione è in grado di immettere fino a 2200 kg di carico utile in orbita polare a 700 km o 1800 kg in orbita elio sincrona a 800 km. Le prove di tenuta alla pressione di esercizio ed ai carichi strutturali di progetto sul primo prototipo di P120C si sono concluse il 17 giugno 2017 nello stabilimento Avio di Colleferro. A marzo del 2018 è stato provato al banco presso il poligono di Salto Quirra il primo modello di Z40. Il 16 luglio 2018 è stato provato con successo il primo dei tre motori P120C necessari alla certificazione propedeutica al primo lancio del Vega C previsto nel corso del 2021.

- Space Rider - In seguito all'esperienza acquisita con l'Intermediate eXperimental Vehicle, l'ESA decise, nel dicembre 2016, di procedere con lo sviluppo di un sistema riutilizzabile di accesso all'orbita bassa. Dopo una prima verifica di fattibilità conclusa a dicembre 2017, il 25 gennaio 2018 iniziò la definizione del progetto preliminare. Per ridurre al minimo i costi di sviluppo e massimizzare il carico utile, lo Space Rider sfrutta elementi derivati dal progetto IXV fondendoli con il progetto del Vega C. Il risultato è uno spazioplano composto di un modulo di servizio orbitale (lo stadio superiore del Vega C modificato con un impianto fotovoltaico da 16 Kw e un sistema di controllo di assetto potenziato) e un modulo di rientro con un volume utile di 1,2 m3 in grado di rientrare a terra e volare di nuovo dopo una leggera manutenzione.

- VEnUS - Il VEnUS (VEGA Electrical nudge Upper Stage) è una evoluzione del modulo orbitale studiato per lo Space Rider con l'obiettivo di permettere al Vega C una maggiore flessibilità nel collocamento di satelliti fino a 1000 kg in particolari orbite fortemente ellittiche o di fuga, nel trasferimento da orbite di parcheggio ad orbite geostazionarie. Si compone di un modulo contenente il sistema di controllo di assetto, quattro serbatoi contenti il gas xeno usato come propellente nei motori elettrici e un modulo per la produzione di energia elettrica mediante pannelli fotovoltaici ripiegabili, computer di navigazione e assetto con sensori stellari, ruote di reazione coadiuvate da sistemi di controllo d'assetto a momento magnetico.

- Vega E - Già a partire dal 2004 fu proposto con il programma "LYRA" lo sviluppo di una versione evoluta del lanciatore che prevedeva un terzo stadio a propellenti liquidi (ossigeno-metano) in sostituzione del terzo e quarto stadio della configurazione iniziale con l'obiettivo di incrementare del 30% le prestazioni del vettore senza impatti significativi sul prezzo del lancio. Una volta definita la versione "consolidata" (Vega C), fu proposta una successiva "evoluzione" (Vega E) con l'obbiettivo di sfruttare al meglio le esperienze ottenute durante il programma di sviluppo Vega utilizzando motori già disponibili o in via di sviluppo, come l'inedito stadio superiore a metano ed ossigeno liquido (denominato VUS, Vega Upper Stage). Il 30 novembre 2017 ne è stato firmato a Parigi un contratto da 53 milioni di euro per la realizzazione dopo il 2024. Saranno introdotte nuove metodologie produttive quali la stampa 3D e sarà aggiornato il sistema di controllo di assetto (con nuovi motori a perossido di idrogeno) e l'avionica. Il 13 novembre 2018 è stata completata con successo la prima prova al banco del prototipo in scala del motore M10 del VUS presso gli stabilimenti Avio di Colleferro. Durante la fase di valutazione preliminare del sistema di lancio (il cui completamento è previsto a fine 2018), sono emerse due configurazioni principali. La prima (VEGA–E light, chiamato anche VEGA–L) è un lanciatore bi-stadio con un carico utile di 400 kg verso l'orbita bassa ed è costituito dal Z40 (attuale secondo stadio del Vega C) e dal VUS. L'altra (VEGA-E heavy) ha prestazioni simili al Vega C ed è composta dal P120C al primo stadio, lo Z40 al secondo ed il VUS come stadio superiore. Il 22 maggio 2019 è stato istituito in Francia un gruppo di lavoro congiunto delle commissioni Affari economici, Affari esteri, Difesa e forze armate francesi che, il 19 novembre 2019, ha redatto un rapporto in cui emergerebbe la raccomandazione per l'Europa, da parte del governo francese, di concentrarsi sullo sviluppo di Ariane 6 limitando conseguentemente lo sviluppo del Vega E al fine di ottenere al massimo solo la riduzione dei costi di lancio di quest'ultimo senza aumentarne le prestazioni. Questa raccomandazione punta ad evitare di aumentare la sovrapposizione tra l’area delle prestazioni di Ariane 6 e quella del Vega E, cioè le orbite ed i carichi servibili da entrambi i vettori, dove i due lanciatori sarebbero quindi in competizione. Nonostante le raccomandazioni del governo francese, sia per la configurazione VEGA-E sia per la VEGA–L sono stati sottoscritti e finanziati i programmi di sviluppo in occasione della conferenza ministeriale europea di Siviglia.

UN’EUROPA FEDERALE?

In conclusione, è chiaro che l’Europa è già in possesso delle necessarie competenze tecnologiche per la messa a punto di un vettore strategico che possa consolidare la propria presenza militare nel consesso militare mondiale.

A questo punto manca una cosa fondamentale:

- una vera federazione di Stati,

- una politica estera comune

- ed un vero presidente in grado di decidere.

Ai posteri l’ardua sentenza!

ENGLISH

FROM THE "ALFA" NUCLEAR MISSILE (1957-1976) TO "VEGA" (1998-2021): an initial basis for a European strategic missile?

The Alfa programme, launched in the 1970s by Italy, focused on a Medium-Range Ballistic Missile produced by Aeritalia and similar to the Polaris A-3. Had it become operational, it would have had a range of over 1600 km, armed with a single 1-megaton nuclear warhead.

On 28 November 1957, the French, Italian and German governments signed a secret agreement for a joint nuclear deterrent. This agreement was rejected by French President Charles de Gaull after his election, as he decided to give France its own independent nuclear arsenal. In the early 1960s Italy found itself surrounded by nations that were pursuing the construction of nuclear weapons. Yugoslavia and Romania had begun to independently develop their own atomic weapons, and were collaborating in the design and development of the new Soko-IAR J-22 Orao fighter-bomber for their use. The government of neutral Switzerland had also decided on 23 December 1958 to equip its armed forces with nuclear weapons.

In 1957, the Navy began work on the conversion of the light cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi into a missile launcher. During the conversion work carried out at the La Spezia Arsenal, it was decided to install, in a special aft deckhouse, four launch shafts for Polaris ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads. This installation of nuclear weapons on a surface ship was part of a newly developed NATO operational concept. The Garibaldi missile launcher rejoined the squadron during 1961, beginning test firings of the wells, followed by test launches of inert and self-propelled simulacra, both with the ship stationary and underway. The first launch of a ballistic missile simulacrum was carried out on 31 August 1963 in the Gulf of La Spezia. Although the tests were all successful, the missiles were never supplied by the US government, as political reasons prevented their planned acquisition. On 5 January 1963, the US government decided to withdraw the PGM-19 Jupiter medium-range ballistic missiles from Italian and Turkish territory, based on post-Cuba Missile Crisis agreements with the Soviet Union. This decision was later approved by the Italian government, and the 36th Strategic Interdiction Aerobrigade was decommissioned on 1 April 1963 and officially disbanded on 21 June of the same year. As an alternative, the Italian government decided to develop its own nuclear programme.

In December 1964, General Paolo Moci decided to seek authorisation from the then Chief of Defence Staff, General Aldo Rossi, to begin the development of a national nuclear deterrent. General Rossi gave his approval in principle, recommending that the initiative be kept under the strictest secrecy. General Moci had numerous discussions with the leading Italian missile expert at the time, Professor Luigi Broglio, who had launched several equatorial satellites from the Mombasa base. In view of the nation's economic possibilities, these discussions led to the idea of building a missile with a range of 3,000 km, which could strike the whole of Europe and North Africa, armed with a 2.5 kg plutonium warhead. The planned production of 100 missiles would have cost as much as bringing the new Lockheed F-104G Starfighter bombers on line.

At the time, the US government was giving high priority to nuclear non-proliferation and pushing for the signing of an international treaty. The Soviet Union made the elimination of the NATO Nuclear Multilateral Force one of the preconditions for its accession to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which was signed on 1 July 1968 by the US, the UK and the Soviet Union. Neither Switzerland, the Balkan countries nor Italy immediately ratified it. The Swiss government acceded to the treaty in 1969, while the Yugoslav and Romanian governments ratified it by March 1970. Western intelligence services indicated that, even after the treaty was signed, Yugoslavia was still developing nuclear weapons at the Vinca Institute, located near Belgrade.

Based on these reports, the Italian government decided to take the appropriate steps to develop an independent nuclear deterrent.

In 1971, the Italian Navy began the study, under the aegis of C.T.S.D.'s G.R.S. (Gruppo di Realizzazione Speciale Interforze), of a domestically produced medium-range ballistic missile. This missile was to be embarked on submarines and large surface units.

Alfa's design envisaged a two-stage solid-fuel missile. For embarked use, the cold launch system was envisaged, in which gas pressure was used to eject the missile from the launch container. The first stage only ignited when the missile was completely out of the launch container.

The first stage was 3.845 m long, weighed 6 959 kg and used 6 050 kg of HTPB five-point star solid grain fuel (composed of 12% aluminium, 15% binder and 73% ammonium perchlorate) licensed from Rocketdyne. The first-stage BPD engine had four carbon-fibre nozzles fitted with a gimbal and coated in graphite. The engine provided a take-off thrust of approximately 25 tonnes (250.00 kN) for 57 seconds. The second stage weighed 950 kg.

The missile weighed 10 695 kg at launch, was 6.50 m long, and had a range of about 1 600 km, which was reduced to 1 000 km with the installation of a warhead weighing 1 000 kg. The warhead comprised a single re-entry vehicle equipped with a 1-megaton thermonuclear warhead. The inertial guidance system was supplied by the French company Sagem, and featured a Type E 38 floating gyroscope control unit.

The main Italian aerospace companies contributed to the Alfa programme. The lead company was Aeritalia (structures and heat shield), while SNIA-BPD Spazio supplied the engine, Sistel the on-board electronics and Selenia the ground control and guidance system. Other minor companies included in the programme were SNIA-Viscosa Laben-Montedel (firing station), Mupes (launch pad), and Motofides/Whitehead.

Between December 1971 and July 1973, several tests were carried out on scale models of the engine at the BPD Spazio plant in Colleferro. The first-stage engine was tested eleven times in static tests, between December 1973 and January 1975, at the Navy's Cottrau balipendio in La Spezia. The first experimental launch of the missile, equipped with an inert second stage, took place from the Salto di Quirra range (Sardinia) at 17:00 on 8 September 1975. The missile reached a range of 25 km in one minute, reaching an altitude of 110 km and falling some 60 km from the range. Two further test missiles were launched from Salto di Quirra, the second on 23 October 1975, while the third and final launch took place on 6 April 1976. All launches were successful.

The development of the Alfa weapon system, which had already cost six billion lire, was stopped at this stage, when the Yugoslav nuclear programme was being abandoned. Under pressure from the United States, Italy signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty on 2 May 1975, while Switzerland ratified the treaty and definitively ended its nuclear programme in 1977. The Alfa missile would have been capable of delivering a one-tonne nuclear warhead to a range of 1600 km, enough to strike Moscow and other targets in European Russia from the Adriatic Sea. The programme's technological legacy flowed into subsequent Italian solid-propellant space launchers, including the Advanced Scout and the Vega project.

THE Vega MISSILE

Vega, an acronym for Vettore Europeo di Generazione Avanzata (European Advanced Generation Carrier), is an operational launcher used by Arianespace, developed in collaboration with the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and the European Space Agency (ESA) to launch small satellites (300 - 1500 kg) into orbit.

The Vega, which takes its name from the star of the same name in the Lyra constellation, is a single-body launcher, without side boosters, with three solid-propellant stages P80, Zefiro 23, Zefiro 9 and a liquid-propellant orbital manoeuvring stage, the AVUM.

Technical development was entrusted to the Italian ELV, a company owned 70% by Avio and 30% by ASI. The initial concept of the launcher project, initially known simply as "Zefiro" from the name of the single model of propeller foreseen in the original configuration, was presented by the then BPD Difesa Spazio to the ASI in 1988, as the successor to the Scout launcher (used by the "Progetto San Marco" programme), which was expected to cease production soon. The final Vega project was launched in 1998 with final approval by the European Space Agency. Italy is the major funder and developer of the programme with a 65% share, followed by France (12.43%), Belgium (5.63%), Spain (5%), the Netherlands (3.5%) and finally, with marginal shares, Switzerland (1.34%) and Sweden (0.8%).

The rocket is designed to carry small payloads, between 300 and 1500 kg, into low or polar orbits, particularly heliosynchronous ones. A special and much appreciated feature is the ability to carry two or three small payloads at the same time and position them correctly on different orbits, an uncommon capability in launchers of such small size.

The launcher consists of a single four-stage body, about 30 metres high, with a maximum diameter of about 3 metres and a take-off weight of 137 tonnes. Unlike many other launchers, the Vega was built in carbon fibre.

THE 4 STAGES OF THE LAUNCHER:

- P80 - Vega's first stage in order of ignition, known as the P80, is the world's largest and most powerful one-piece solid propellant thruster. This programme was led by the Centre national d'études spatiales (CNES) in Évry and was funded by France (66%), Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy. In addition to building the first Vega stage, the P80 project also aimed to develop new technologies useful for future developments of the Ariane series. The design of the stage was entrusted to the Italian company Avio (engine) and the French-Italian company Europropulsion (integration), as well as minor orders to the Belgian company SABCA (control system), the French company Snecma (exhaust nozzle) and the Dutch company Stork B.V. (ignition system). The stage is 11.20 metres high, has a diameter of 3 metres and weighs 96.263 tonnes, of which 87.710 tonnes is propellant. The thrust produced by the engine, equivalent to 3 015 kN, is delivered for 109.9 seconds. The P80 underwent two ignition tests, the first of which took place in Kourou on 30 November 2006 and was successfully completed: the engine performed very similarly to expectations. The development of the project was then concluded with a second ignition test in Kourou on 4 December 2007, during which a new steerable nozzle was used. The engine generated thrust in line with expectations, allowing the stage to be declared ready for flights.

- Zefiro 23 and Zefiro 9 - ZEFIRO = ZEro FIrst stage ROcket motor derives from the original configuration of VEGA, which foresaw two equal Zefiros for the first two stages of the Launcher, called zero stage and first stage. Zefiro 23 and Zefiro 9, where the number represents the weight in tonnes foreseen at the beginning of the design, are respectively the second and third stages of Vega. They were developed, built and tested by Avio, with the collaboration of SABCA for the control system. The Zefiro 23 underwent two firing tests at the Salto di Quirra firing range, the first on 26 June 2006, the second on 27 March 2008. Both tests were successful and the Zefiro 23 was declared airworthy. Zefiro 9 also underwent two firing tests at Salto di Quirra. The first, on 20 December 2005, was a complete success; however, during the second, on 27 March 2008, which followed an overhaul on the basis of data from the first test, the engine showed an anomalous drop in internal pressure. The failure caused a delay in the development of the launcher, but on 23 October 2008, during a new test, the engine showed satisfactory performance, also thanks to a new nozzle and a greater quantity of propellant.

- AVUM - The fourth stage, called the Attitude and Vernier Upper Module, houses the engine responsible for the final insertion of the payload into orbit. Unlike the previous stages, which use solid propellant, the fourth stage uses a liquid propellant, consisting of asymmetric dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) and nitrogen tetraoxide as an oxidiser. The orientation of the module is adjusted by means of a system using hydrazine. Above the propulsion system is a module that houses the main components of the launcher's avionics.

- The stage is 2.04 metres high, has a diameter of 2.18 metres and weighs 1265 kilograms, of which up to 577 kg is propellant. The thrust provided by the engine for 667 seconds is equivalent to 2.45 kN. The module is of Ukrainian and Spanish technology and production: the engine is developed by the Yuzhnoye company while a Spanish subsidiary of EADS is responsible for the structure and body. There have been discussions in the past about the possibility of replacing the Ukrainian engine with a German one to make the module a total European production.

Load coverage

The payload cover, the so-called payload fairing, was designed and manufactured by Swiss company RUAG Space. It has a diameter of 2.6 metres, a height of 7.88 metres and a mass of 540 kg.

Launch and qualification tests

On 26 June 2006, the Zefiro 23 second-stage engine firing test was completed at the Interforce Experimental and Training Range in Quirra (Sardinia). The test allowed fundamental information to be gathered on the characteristics of the stage: variations in pressure, temperature and combustion speed, thrust profile, control of thrust orientation through the electromechanical actuators that drive the nozzle. The parameters collected made the test a complete success. On 30 November 2006, the ignition test of the motors of the first stage P80 of the launcher was successfully carried out at the space centre of French Guyana. On 5 December 2007, the final version of the P80 engine was successfully tested at the Kourou Space Centre in French Guyana.

First launch

Vega's first flight, flight code VV01, initially scheduled for November 2010, took place on 13 February 2012 from the Centre spatial guyanais in Kourou, putting nine satellites into orbit, including the Italian LARES, which stands for LAser Relativity Satellite (a satellite designed to measure, with an accuracy of 1%, the Lense-Thirring effect of general relativity), built with the collaboration of La Sapienza University, and ALMASat-1, built at the Forlì engineering centre of the University of Bologna.

VERTA Programme

After the first flight, the European Space Agency planned five launches as part of the VERTA (VEga Research and Technology Accompaniment) programme, aimed at convincing potential users of the validity of the launcher. During these flights, VEGA carried four European Space Agency satellites into orbit: Proba-V (Earth observation), ADM-Aeolus (study of the atmosphere), LISA Pathfinder (study of gravitational waves) and the Intermediate Experimental Vehicle (IXV). Alongside the main payloads, nanosatellites were also launched for educational purposes, such as e-st@r from the Politecnico di Torino. The VERTA programme envisaged a minimum frequency of two launches per year, with the aim of demonstrating VEGA's potential for commercial exploitation, and ended with the launch of the LISA Pathfinder demonstrator.

Second launch

The second launch (first launch of the VERTA programme), flight code VV02, took place at 4 a.m. (Italian time) on 7 May 2013, carrying into orbit ESA's Proba-V satellite, capable of performing a global survey of vegetation, Estonia's first satellite, ESTCube-1, and a Vietnamese satellite, VNREDSAT.

Third launch

On 30 April 2014 at 3.35 a.m. (Italian time), the third launch of the launcher took place, the first exclusively commercial launch. The launch took place from platform number 1 of the Centre spatial guyanais in Kourou, French Guiana, the same platform used for the Ariane 1 rockets. This launch put into orbit a satellite, the KazEOSat-1, weighing a total of 900 kg, which will provide multispectral and high-resolution panchromatic images of the entire planet, to be used for monitoring and mapping the planet, supporting the management of natural disasters and pure surveillance of the territory.

Fourth launch

The fourth launch took place regularly on 11 February 2015 and brought the European experimental vehicle IXV into a sub-orbital trajectory. During the flight, the AVUM fourth stage briefly entered orbit and then performed a de-orbiting manoeuvre as planned.

Fifth launch

The fifth launch (the first of the Arianespace-ELV supply batch) took place on 23 June 2015 at 3:51 a.m. Italian time from the Kourou base to put the Sentinel 2A satellite in orbit as part of the European Copernicus programme (putting into orbit a dozen satellites). The task of this satellite is to reveal, for the next seven years, the "colours" of the earth, thus monitoring the state of health of our planet, with particular attention to agricultural areas and forests. The Sentinel 1A satellite was launched into orbit on 3 April 2014 by a Soyuz rocket.

Sixth launch

The sixth launch (the fifth and last of the VERTA programme) took place again in Kourou on 3 December 2015 at 04:04:00 UTC, to put into orbit the Airbus LISA Pathfinder satellite for which an operational life of one year was initially planned, later extended until June 2017.

Arianespace-ELV supply

In November 2013, a contract was signed between Arianespace and ELV for the supply of ten VEGA launchers, which will be launched within three years after the end of the VERTA programme.

Seventh launch

The seventh launch, which took place at 01:43 UTC on 16 September 2016, allowed the placing into orbit of four satellites of the "Terra Bella" Earth surface sensing platform and the PeruSAT-1 observation satellite.

Eighth launch

With the eighth launch at 13:51 UTC on 5 December 2016, the Turkish earth observation satellite Gokturk-1 was put into orbit.

Ninth launch

On 7 March 2017 at 01:49 UTC, the Sentinel 2B satellite was successfully launched as part of the European Copernicus project to monitor the Earth's landmass and coastal waters.

Tenth launch

With the launch on 2 August 2017, two Earth observation satellites were put into orbit, the OPTSAT-3000 on behalf of the Italian Ministry of Defence and the French-Israeli VENµS satellite.

Eleventh launch

With the VV11 mission, the Mohammed VI-A satellite was launched on 8 November 2017 on behalf of Morocco. Initially it was planned that the payload of the VV11 mission would be ESA's ADM-Aeolus satellite, but during 2017 it was decided to postpone the Aeolus launch to 2018 and to assign the Moroccan satellite the last Vega launch of 2017.

Twelfth launch

Vega's first launch of 2018 saw ESA's ADM-Aeolus meteorological satellite for accurate wind profiling put into orbit. Initially scheduled for 21 August, the launch was postponed by one day due to adverse weather conditions at altitude.

Thirteenth launch

The launch of the second Mohammed VI satellite on behalf of Morocco took place on 21 November 2018, with the VV13 mission. As in the previous year, the nature of the payload remained confidential until a few weeks before the launch. In its place, the PRISMA satellite was in fact planned, which was later postponed to March 2019.

Fourteenth launch

On the night of 21-22 March 2019, the Italian Space Agency's PRISMA mission was launched, the first satellite developed in Europe for hyperspectral Earth observation. Thanks to its sensors capable of separately detecting more than 200 bands in the ultraviolet, visible and infrared spectrum, it is possible to acquire images of the Earth's surface that also contain information on the chemical and physical composition of the objects observed.

Fifteenth launch - VV15 mission failure

On 11 July 2019, the VV15 mission marked the first failure of the Vega launcher. Two minutes after liftoff, shortly after the second stage was ignited, an anomaly occurred that led to the deviation from the planned trajectory. The mission therefore ended with the loss of the payload, the Falcon Eye 1 military satellite.

The preliminary report of the Independent Commission that investigated the causes of the mission failure, established that at 130 seconds after liftoff (T+130), 14 seconds after second-stage ignition, there was a rapid and violent structural failure of the front part of the Zefiro 23 engine that caused the launcher to break into two parts. At T+135 the trajectory started to deviate from the nominal one and at T+213 the self-destruction of the launcher was commanded from the ground. The last telemetry signal was received at T+314. The Commission proposed a verification and corrective action plan to be completed before the resumption of the Vega launch campaign, scheduled for Q1 2020.

Subsequent analysis and tests on full-scale and full-scale models identified, reproduced and confirmed that the structural failure was caused by a defect in the thermal insulation in the upper part of Zefiro 23 which, by causing a leak of high-temperature gas, led to its malfunction.

Sixteenth launch - Return to service

More than a year after the failure of the VV15 mission, the 16th launch of the Vega launcher was successfully completed on 3 September 2020. With a payload of 53 satellites from 21 customers from 13 different countries, it demonstrated the capability of the Ssms (Small Spacecraft Mission Service) system to release micro and nano satellites into different orbits in a single mission.

The mission, initially scheduled for September 2019, was first postponed to March 2020 following quality checks on the production system dictated by the investigation into the previous mission and then, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, to August 2020. However, periodic winds at equatorial latitudes, incompatible with the mission profile, caused a series of delays to the launch, which was rescheduled for 2 September. After yet another delay due to a typhoon hitting the telemetry control station in South Korea, the Vega was finally launched on the night of 2 to 3 September 2020.

Seventeenth launch - VV17 mission failure

On 17 November 2020, a new anomaly occurred during the VV17 mission, which ended just eight minutes after launch. After proper operation of the first, second and third stages, a fourth stage anomaly occurred causing the launcher's trajectory to deviate.

Future developments:

- Vega C - The development of the Vega C version was formally approved on 12 August 2015 and envisages the use of a P120C for the first stage (an enlarged version of the P80, also used as an Ariane 6 booster), a Z40 at the second stage, a Z9 for the third and the AVUM+ (which has 20% more propellant than the standard AVUM) for the fourth stage. This version is capable of delivering up to 2200 kg of payload in polar orbit at 700 km or 1800 kg in helium-synchronous orbit at 800 km. Tests to withstand operating pressure and design structural loads on the first P120C prototype were completed on 17 June 2017 at Avio's Colleferro plant. In March 2018, the first Z40 model was bench tested at the Salto Quirra range. On 16 July 2018, the first of the three P120C engines necessary for the certification preparatory to the first launch of the Vega C, scheduled for 2021, was successfully tested.

- Space Rider - Following the experience gained with the Intermediate eXperimental Vehicle, ESA decided in December 2016 to proceed with the development of a reusable low orbit access system. After an initial feasibility check concluded in December 2017, the definition of the preliminary design began on 25 January 2018. To minimise development costs and maximise payload, the Space Rider takes advantage of elements derived from the IXV project by merging them with the Vega C design. The result is a spaceplane consisting of an orbital service module (the upper stage of the Vega C modified with a 16 kW photovoltaic system and an upgraded attitude control system) and a re-entry module with a useful volume of 1.2 m3 capable of re-entering the ground and flying again after light maintenance.

- VEnUS - The VEnUS (VEGA Electrical nudge Upper Stage) is an evolution of the orbital module designed for the Space Rider with the aim of allowing the Vega C greater flexibility in placing satellites of up to 1000 kg in particular highly elliptical orbits or escape orbits, in transferring from parking orbits to geostationary orbits. It consists of a module containing the attitude control system, four tanks containing the xenon gas used as a propellant in the electric motors and a module for the production of electrical energy through foldable photovoltaic panels, navigation and attitude computers with star sensors, reaction wheels assisted by magnetic moment attitude control systems.

- Vega E - As early as 2004, with the "LYRA" programme, the development of an advanced version of the launcher was proposed, which envisaged a third stage using liquid propellants (oxygen-methane) to replace the third and fourth stages of the initial configuration, with the objective of increasing the launcher's performance by 30% without significant impact on the launch price. Once the "consolidated" version (Vega C) had been defined, a subsequent "evolution" (Vega E) was proposed with the aim of making the most of the experience gained during the Vega development programme using engines already available or under development, such as the unprecedented methane and liquid oxygen upper stage (called VUS, Vega Upper Stage). On 30 November 2017, a €53 million contract was signed in Paris for implementation after 2024. New production methods such as 3D printing will be introduced and the attitude control system (with new hydrogen peroxide engines) and avionics will be upgraded. On 13 November 2018, the first bench test of the M10 engine scale prototype of the VUS was successfully completed at Avio's Colleferro facilities. During the preliminary evaluation phase of the launch system (scheduled for completion at the end of 2018), two main configurations emerged. The first (VEGA-E light, also called VEGA-L) is a two-stage launcher with a payload of 400 kg towards low orbit and consists of the Z40 (current second stage of the Vega C) and the VUS. The other (VEGA-E heavy) has similar performance to the Vega C and consists of the P120C on the first stage, the Z40 on the second and the VUS as the upper stage. On 22 May 2019, a joint working group of the Economic Affairs, Foreign Affairs, Defence and French Armed Forces committees was set up in France, which, on 19 November 2019, drew up a report in which a recommendation emerged for Europe, on the part of the French government, to focus on the development of Ariane 6 by consequently limiting the development of the Vega E in order to obtain at most only the reduction of the latter's launch costs without increasing its performance. This recommendation aims to avoid increasing the overlap between the performance area of Ariane 6 and that of Vega E, i.e. the orbits and loads that can be served by both launchers, where the two launchers would therefore compete. Despite the recommendations of the French government, both the VEGA-E and VEGA-L configurations were signed and funded at the European Ministerial Conference in Seville.

A FEDERAL EUROPE?

In conclusion, it is clear that Europe already possesses the necessary technological expertise to develop a strategic carrier that can consolidate its military presence in the world military arena.

One fundamental thing is missing at this point:

- a true federation of states,

- a common foreign policy

- and a real president capable of making decisions.

Let posterity be the judge of that!

(Web, Google, Wikipedia, Circolodel53, You Tube)