Il Mil Mi-12 (conosciuto in russo anche come V-12, in cirillico Миль Ми-12 o В-12, nome in codice NATO Homer, Omero) fu un elicottero da trasporto pesante sperimentale che venne sviluppato dal'ufficio di progettazione sovietico Mil a partire dalla metà degli anni sessanta. Detiene tuttora il primato di più grande elicottero mai costruito. Nel 2009, fu protagonista di una bufala internazionale che divenne oggetto dell'attenzione dei media di diverse parti del mondo: venne annunciata l'entrata in servizio di un Mi-12 modificato per diventare un hotel di lusso e soprannominato "Hotelicopter".

Storia del progetto

Il Mi-12 nacque dalla risposta della Mil a una specifica emessa nel 1965 dall'aeronautica militare sovietica (Sovetskie Voenno-vozdušnye sily, o VVS), la quale richiedeva un elicottero da trasporto pesante il cui ruolo principale avrebbe dovuto essere quello di trasportare voluminose componenti di missili spaziali dall'aeroporto dove giungevano a bordo di aeroplani di grandi dimensioni (come l'Antonov An-22) fino al sito di lancio. Un elicottero come questo avrebbe potuto avere anche un impiego civile con la compagnia di bandiera sovietica Aeroflot, in special modo per facilitare i collegamenti con la Siberia; in ogni caso la componente militare della specifica risultava preponderante.

Nonostante la VVS avesse richiesto un elicottero con due rotori in tandem, la Mil ricevette ben presto l'autorizzazione a procedere verso una configurazione con i due rotori affiancati (rotori trasversali); questo, stando all'ufficio di progettazione, avrebbe garantito una migliore affidabilità, stabilità e resistenza all'affaticamento dei materiali.

Tecnica

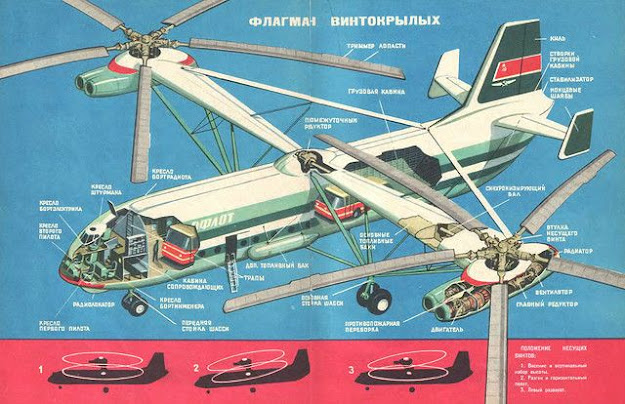

La fusoliera dell'elicottero assunse dunque l'aspetto di un consueto aeroplano ad ala fissa; dalla sommità di tale fusoliera si dipartivano due alette, caratterizzate da una marcata rastremazione inversa, alle cui estremità erano collocati i due gruppi motopropulsori. Ognuno di essi era costituito da una coppia di motori a turbina affiancati, azionanti un rotore a cinque pale; pur essendo derivati direttamente dal motore già installato sull'elicottero Mil Mi-6 (il Soloviev D-25V) i Soloviev D-25VF del Mi-12 avevano ricevuto un compressore migliorato, e la loro temperatura operativa era stata aumentata; la loro potenza era così passata da 5 500 a 6 500 cavalli vapore all'albero di trasmissione.

I due rotori erano sincronizzati in modo da non entrare mai in contatto, nemmeno nel caso in cui uno dei motori avesse cessato di funzionare. Il fatto che il rotore destro ruotasse in senso orario e il sinistro in senso antiorario (dal punto di vista di un osservatore posto in alto) rendeva poi superfluo il rotore anticoppia di coda. Il carburante era contenuto in due serbatoi cilindrici collocati orizzontalmente in basso, ai lati della fusoliera. Il carrello d'atterraggio a sei ruote era del tipo triciclo anteriore, con le due gambe principali (quelle posteriori) vincolate alle gondole dei motori e alla fusoliera da un sistema di travi e montanti.

Il Mi-12 poteva caricare un gran numero di passeggeri (fino a 120) ma sugli esemplari costruiti vennero predisposti solo 50 posti a sedere, perché il compito principale dell'elicottero era quello di sollevare grandi quantità di merci, trasportando solo il personale di qualche impianto petrolifero o missione spaziale. Per il trasporto e l'ancoraggio del carico era installata una gru con quattro attacchi capaci di sostenere 2 500 chilogrammi ciascuno o, in alternativa, di sollevare un singolo carico da 10 000 chilogrammi. Il cono posteriore della fusoliera comprendeva una rampa di carico con grandi portelloni che consentivano di immagazzinare oggetti voluminosi all'interno dell’aeromobile.

Impiego operativo

Vennero costruiti solo due prototipi del Mil Mi-12, il primo dei quali portò a termine il suo volo inaugurale il 10 luglio 1968. Esso si schiantò al suolo in un cattivo atterraggio nel corso del 1969; l'incidente, che danneggiò l'elicottero in modo grave ma non ebbe conseguenze fatali, fu causato probabilmente da un problema legato ai motori.

Rimesso in condizioni di volo, il prototipo subì un intenso programma di test nel corso del 1969 e, prima della fine dell'anno, infranse sette record mondiali: particolarmente degno di nota il volo in cui, il 22 febbraio, un carico di 31 030 chilogrammi venne sollevato a 2 951 metri di quota (battendo il record per il massimo carico utile sollevato a 2 000 metri) e quello in cui, il 6 agosto, un carico di 40 204,5 chilogrammi venne sollevato a 2 255 metri (battendo il record per il massimo carico portato a 2 000 metri e quello per il rapporto carico-quota nelle classi 35 000 e 40 000 chilogrammi).

Nel 1971 l'elicottero partecipò al salone aeronautico di Le Bourget, a Parigi.

Il secondo prototipo (che, curiosamente, era immatricolato con lo stesso codice del primo, СССР-21142) non volò che nel 1973; anch'esso fece poi una comparsa al salone di Le Bourget.

Furono probabilmente dei problemi di ordine tecnico a causare, nel 1974, l'abbandono del progetto Mi-12 in favore del Mi-26, che avrebbe volato per la prima volta nel 1977.

Esemplari attualmente esistenti

Il primo prototipo del Mil Mi-12 è esposto vicino alla fabbrica Mil di Panki, nel rajon di Ljubereckij.

Il secondo prototipo è conservato al museo centrale della Federazione Russa delle aeronautiche militari situato presso l'aeroporto di Monino, a 38 km da Mosca.

Hotelicopter

Negli anni 2000, molto dopo la fine della sua vita operativa, il Mil Mi-12 fu protagonista di una bufala internazionale che divenne oggetto dell'attenzione dei media di diverse parti del mondo. All'inizio del 2009, pochi giorni prima del 1º aprile, venne annunciata la prossima entrata in servizio di un "Hotelicopter" basato sulla struttura del Mi-12, ma radicalmente modificato per diventare un hotel di lusso volante. Il nuovo aeromobile, dotato di tutti i comfort, avrebbe avuto una lunghezza di 42 metri e quattro piani, per un'altezza di 28 metri. La bufala, scoperta come tale quasi immediatamente, è stata giudicata dal quotidiano statunitense Christian Science Monitor come una delle cinque migliori trovate per il pesce d'aprile di tutti i tempi, e dal Times inglese come uno dei dieci migliori "pesci d'aprile sui viaggi" di sempre.

ENGLISH

The Mil V-12 (NATO reporting name: Homer), given the project number Izdeliye 65 ("Item 65"), is the largest helicopter ever built. The designation "Mi-12" would have been the name for the production helicopter and was not applied to the V-12 prototypes.

Design and development

Design studies for a giant helicopter were started at the Mil OKB in 1959, receiving official sanction in 1961 by the GKAT (Gosudarstvenny Komitet po Aviatsionnoy Tekhnike - State Committee on Aircraft Technology) instructing Mil to develop a helicopter capable of lifting 20 to 25 t (44,000 to 55,000 lb). The GKAT directive was followed by a more detailed specification for the V-12 with hold dimensions similar to the Antonov An-22, intended to lift major items of combat materiel as well as 8K67, 8K75 and 8K82 inter-continental ballistic missiles (ICBM).

Design limitations forced Mil to adopt a twin rotor system but design studies of a tandem layout, similar to the Boeing CH-47 Chinook, revealed major problems. The single rotor layouts also studied proved to be non-viable, leading to the transverse layout chosen for the finished article.

The transverse rotor system of the V-12, which eliminates the need for a tail rotor, consists of two Mil Mi-6 transmission systems complete with rotors mounted at the tips of the approximately 30 m (98 ft) span inverse tapered wings. Although the first use by Mil, the transverse system had been used by several of the early helicopters, including the Focke-Wulf Fw 61, Focke-Achgelis Fa 223 Drache and Kamov Ka-22 Vintokryl convertiplane.

Construction of the V-12 first prototype, after exhaustive testing with test-rigs and mock-ups including a complete transmission system, began at Panki in 1965. The airframe was largely conventional, using stressed skin construction methods with high strength parts machined from solid metal blocks. The large fuselage accommodated the 28.15×4.4×4.4 m (92.4×14.4×14.4 ft) cabin and crew section in the extreme nose, housing a pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer and electrical engineer in the lower cockpit, with the navigator and radio operator in the upper cockpit.

At the aft end of the fuselage access to the cabin is gained by large clamshell doors and a drop down cargo ramp with inbuilt retractable support jacks. Doors in the fuselage also give access to the cargo hold: two on the starboard side and three on the port side. Above the rear fuselage is a very large fin and rudder, with a moderately sized tailplane with dihedral fitted with end-plate fins (not fitted for the first flight).

The fixed undercarriage consists of large paired main-wheel units on oleo-pneumatic levered shock absorbers mounted at the junction of a strut system supporting the rotor systems and wings and connected to the centre fuselage by a tripod strut structure with the nose-leg attached aft of the crew section. A pair of bumper wheels are mounted at the rear of the fuselage keel and fixed support pads ensure that the cargo ramp is extended to the correct angle. Long braced struts also connected the transmission units to the rear fuselage forward of the fin. Cargo handling is done by means of a forklift or electric hoists on traveling beams.

The power system and wings are mounted above the centre fuselage with interconnecting shafts ensuring synchronisation of the main rotors which overlap by about 3 m (9.8 ft). Drag and lift losses are reduced by the inverse taper wings with minimum chord in regions of strongest down-wash. The interconnecting shafts also ensured symmetrical lift distribution in the event of an engine failure. To optimise control in roll and yaw the rotors are arranged to turn in opposite directions with the port rotor turning anti-clockwise and the starboard rotor turning clockwise, ensuring that the advancing blades pass over the fuselage.

Each power unit comprises two Soloviev D-25VF turbo-shaft engines mounted below the main gearboxes which each drive five-bladed 35 m (115 ft) diameter rotors and their synchronisation shafts which run from wing-tip to wing-tip. Each paired engine pod has large access panels which open up for maintenance access and also form platforms for servicing crews to operate from.

Control of the V-12 presented several problems to the designers and engineers due to the sheer size as well as the rotor layout. The pilot and co-pilot sat in the lower flight deck with a wide expanse of windows to give excellent visibility. Using conventional cyclic stick, collective lever and rudder pedals the pilots input their commands in a conventional fashion. Roll control is by differential collective pitch change on the left and right rotors, ensuring that sufficient lift is generated to prevent inadvertent sink. Yaw in the hover or low air speeds is achieved by tilting the rotor discs forward and backward differentially depending on direction of yaw required. At higher air speeds differential rotor control is gradually supplanted by the large aerodynamic rudder on the fin. Ascent and descent are controlled by the collective lever increasing or decreasing the pitch of both rotors simultaneously. Large elevators on the tailplane help control the fuselage attitude and provide reaction to pitching moments from the wing and variation on rotor disc angle.

The control system is complex due to the sheer size of the aircraft and the need to compensate for aeroelastic deformation of the structure, as well as the very large friction loads of the control rods, levers etc. To keep the control forces felt by the pilots to a minimum, the control system has three distinct stages. Stage one is the direct mechanical control from pilot input forces which are fed into a second stage, intermediate powered control system with low-powered hydraulic boosters transferring commands to stage three, the high-powered rapid action control actuators at the main gearboxes operating the swashplates directly.

Operational history

Construction of the first prototype was completed in 1968. A first flight on 27 June 1967 ended prematurely due to oscillations caused by control problems; one set of main wheels contacted the ground hard bursting a tyre and bending a wheel hub. The cause of the oscillations proved to be a harmonic amplification of vibrations in the cockpit floor feeding back into the control column when a roll demand was input into the cyclic stick. It was widely but erroneously reported in the Western press that the aircraft had been destroyed.

The first prototype, given the registration SSSR-21142, made its first flight on 10 July 1968 from the Mil factory pad in Panki to the Mil OKB test flight facility in Lyubertsy. In February 1969, the first prototype lifted a record 31,030 kg (68,410 lb) payload to 2,951 m (9,682 ft). On 6 August 1969, the V-12 lifted 44,205 kg (97,455 lb) to a height of 2,255 m (7,398 ft), also a world record.

The second prototype was also assembled at the Mil experimental production facility in Panki but sat in the workshop for a full year awaiting engines, flying for the first time in March 1973 from Panki to the flight test facilities in Lyubertsy. Curiously the second prototype was also registered SSSR-21142.

The prototype V-12s outperformed their design specifications, setting numerous world records which still stand today, and brought its designers numerous awards such as the prestigious Sikorsky Prize awarded by the American Helicopter Society for outstanding achievements in helicopter technology. The V-12 design was patented in the United States, United Kingdom, and other countries.

Despite all of these achievements the Soviet Air Force refused to accept the helicopter for state acceptance trials for many reasons, the main one being that the V-12's most important intended mission no longer existed, i.e. the rapid deployment of heavy strategic ballistic missiles. This also led to a reduction in Antonov An-22 production.

In May–June 1971, the first prototype V-12 SSSR-21142 made a series of flights over Europe culminating in an appearance at the 29th Paris Air Show at Le Bourget wearing exhibit code H-833.

All development on the V-12 was stopped in 1974. The first prototype remained at the Mil Moscow Helicopter Plant in Panki-Tomilino, Lyuberetsky District near Moscow and is still there today (7 March 2017) at 55°40′2″N 37°55′56″E. The second prototype was donated to Central Air Force Museum 50 km (31 mi) east of Moscow for public display.

World records

Records are certified by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. The V-12 first prototype has held eight world records, four of which are still current, in the FAI E1 General class for rotorcraft powered by turbine engines. The aircraft was crewed by:

22 February 1969

Pilot - Vasily Kolochenko

Crew - L.V. Vlassov, V.V. Journaliov, V.P. Bartchenko, S.G. Ribalko, A.I. Krutchkov

6 August 1969

Pilot - Vasily Kolochenko

Crew - L.V. Vlassov, V.V. Juravlev, V.P. Bartchenkov, S.G. Ribalko, A.I. Krutchkov.

Variants

V-12

OKB designation of the two prototypes of the proposed Mi-12 production version.

Mi-12

Designation reserved for the expected production version.[1]

Mi-12M

A further proposed refinement of the V-16 with two 15,000 kW (20,000 hp) Soloviev D-30V (V - Vertolyotny - helicopter) turboshafts driving six bladed rotors, to transport 20,000 kg (44,000 lb) over 500 km (310 mi) or 40,000 kg (88,000 lb) over 200 km (120 mi). The M-12M was cancelled at the mock-up stage when the V-12 development programme was cancelled.

Specifications (V-12)

General characteristics

- Crew: 6 (pilot, copilot, flight engineer, electrician, navigator, radio operator)

- Capacity: 196 passengers

- normal 20,000 kg (44,000 lb)

- maximum 40,000 kg (88,000 lb)

- Length: 37 m (121 ft 5 in)

- Wingspan: 67 m (219 ft 10 in) across rotors

- Height: 12.5 m (41 ft 0 in)

- Empty weight: 69,100 kg (152,339 lb)

- Gross weight: 97,000 kg (213,848 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 105,000 kg (231,485 lb)

- Freight compartment: 28.15×4.4×4.4 m (92.4×14.4×14.4 ft)

- Powerplant: 4 × Soloviev D-25VF turboshaft engines, 4,800 kW (6,500 shp) each 26,000 HP total

- Main rotor diameter: 2× 35 m (114 ft 10 in)

- Main rotor area: 962 m2 (10,350 sq ft) two 5-bladed rotors located transversely, area is per rotor (1 924 m2 total area).

Performance

- Maximum speed: 260 km/h (160 mph, 140 kn)

- Cruise speed: 240 km/h (150 mph, 130 kn)

- Range: 500 km (310 mi, 270 nmi)

- Ferry range: 1,000 km (620 mi, 540 nmi) with external fuel tanks

- Service ceiling: 3,500 m (11,500 ft)

- Disk loading: 50.5 kg/m2 (10.3 lb/sq ft) at gross weight

- Hovering ceiling in ground effect: 600 m (2,000 ft)

- Hovering ceiling out of ground effect: 10 m (33 ft).

Avionics

AP-44 autopilot

VUAP-2 EXPERIMENTAL AUTOPILOT

ROZ-1 Lotsiya weather and navigational radar.

(Web, Google, Wikipedia, You Tube)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento

Nota. Solo i membri di questo blog possono postare un commento.