Nell'impresa di Alessandria sei uomini della Xª Flottiglia MAS della Regia Marina, a bordo di tre mezzi d'assalto subacquei denominati colloquialmente "maiali" e tecnicamente siluri a lenta corsa (SLC), penetrarono nel porto di Alessandria d'Egitto ed affondarono con testate esplosive le due navi da battaglia britanniche HMS Queen Elizabeth (33.550t) e HMS Valiant (27.500 t), danneggiando inoltre la nave cisterna Sagona (7.750t) ed il cacciatorpediniere HMS Jervis (1.690t). Quella che è senz'altro la più celebre delle azioni della Xª Flottiglia MAS, denominata operazione G.A. 3, venne effettuata nella notte tra il 18 ed il 19 dicembre 1941. Si trattò di una sorta di rivincita delle forze armate italiane per le gravi perdite navali subite nella notte di Taranto (novembre 1940) e proiettò nella leggenda i nomi di Borghese e del suo sommergibile, lo Scirè.

La preparazione

La preparazione dell'attacco, per quanto competeva agli operatori della Xª, venne attuata con la massima meticolosità. L'allenamento del personale era pesantissimo, i materiali sempre all'avanguardia. Non altrettanto valido risulterà invece il supporto informativo, soprattutto per quanto riguarda le informazioni fornite dal SIM sulla situazione all'esterno del porto e per il piano di fuga.

L’attacco

La notte del 3 dicembre il sommergibile Sciré comandato dal tenente di vascello Junio Valerio Borghese lasciò La Spezia per la missione G.A.3. Dopo uno scalo a Lero, nell'Egeo, per imbarcare gli operatori dei mezzi d'assalto giunti sul posto dopo il trasferimento aereo dall'Italia, il 14 dicembre il sommergibile si diresse verso la costa egiziana per l'attacco previsto nella notte del 17. Una violenta mareggiata però fece ritardare l'azione di un giorno.

La notte del 18, con condizioni del mare ottimali, approfittando dell'arrivo di tre cacciatorpediniere che obbligarono i britannici ad aprire un varco nelle difese del porto, i tre SLC (Siluro a Lenta Corsa), pilotati ciascuno da due uomini, penetrarono nella base per dirigersi verso i loro obiettivi. Gli incursori dovevano giungere sotto la chiglia del proprio bersaglio, piazzare la carica d'esplosivo e successivamente abbandonare la zona dirigendosi a terra e autonomamente cercare di raggiungere il sommergibile che li avrebbe attesi qualche giorno dopo al largo di Rosetta.

L'equipaggio Durand de la Penne - Bianchi sul maiale nº 221 puntò verso la nave da battaglia Valiant. Senza la collaborazione del secondo, colpito da un malore a causa di malfunzionamento al respiratore, de la Penne trascinò sul fondo il proprio mezzo, riuscendo a posizionarne la carica esplosiva sotto la carena della nave da battaglia prima di affiorare, essere avvistato, catturato e portato proprio sulla corazzata. Dopo poco, gli inglesi catturarono anche Bianchi, che era risalito alla superficie e si era aggrappato ad una boa di ormeggio della corazzata, e lo rinchiusero nello stesso compartimento sotto la linea di galleggiamento nel quale avevano portato Durand de la Penne, nella speranza di convincerli a rivelare il posizionamento delle cariche. Alle 05:30, a mezz'ora dallo scoppio, de la Penne chiamò il personale di sorveglianza per farsi condurre dal comandante della nave Morgan ed informarlo del rischio corso dall'equipaggio; ciò nonostante questi fece riportare l'ufficiale italiano dov'era. All'ora prevista l'esplosione squarciò la carena della corazzata provocando l'allagamento di diversi compartimenti mentre molti altri venivano invasi dal fumo; anche il compartimento che ospitava gli italiani venne interessato dall'esplosione e una catena smossa dall'esplosione ferì alla testa Durand De La Penne; ma i due italiani riuscirono ad uscire dal locale e ad andare in coperta da dove vennero evacuati insieme al resto dell'equipaggio.

Martellotta e Mario Marino, sul maiale nº222, costretti a navigare in superficie a causa di un malore del primo, condussero il loro attacco alla petroliera Sagona. Questa nave era un obiettivo assegnato dal comandante Borghese in subordine, se constatata l'assenza in porto della portaerei in forza alla Mediterranean Fleet. Dopo aver preso terra vennero anch'essi catturati dagli egiziani. Intorno alle sei del mattino successivo ebbero luogo le esplosioni. Quattro navi furono gravemente danneggiate nell'impresa: oltre alle tre citate anche il cacciatorpediniere HMS Jervis, ormeggiato a fianco della Sagona, fu infatti vittima delle cariche posate dagli assaltatori italiani.

Antonio Marceglia e Spartaco Schergat sul maiale nº 223, in una «missione perfetta», «da manuale» rispetto a quelle degli altri operatori, attaccarono invece la Queen Elizabeth, alla quale agganciarono la testata esplosiva del loro maiale, quindi raggiunsero terra e riuscirono ad allontanarsi da Alessandria, per essere catturati il giorno successivo, a causa dell'approssimazione con la quale il servizio segreto militare italiano, il SIM, aveva preparato la fuga: vennero date ai palombari banconote che non avevano più corso legale in Egitto e per cercare di cambiare le quali l'equipaggio perse tempo. Nonostante il tentativo degli italiani di spacciarsi per marinai francesi appartenenti all'equipaggio di una delle navi internate in rada, vennero riconosciuti e catturati.

Le conseguenze:

“…sei italiani equipaggiati con materiali di costo irrisorio hanno fatto vacillare l'equilibrio militare in Mediterraneo a vantaggio dell’Asse…” Winston Churchill.

Sebbene l'azione fosse stata un successo, le navi si adagiarono sul fondo, e non fu immediatamente possibile avere la certezza che non fossero in grado di riprendere il mare. Nonostante tutto, le perdite di vite umane furono molto contenute: solo 8 marinai persero la vita.

L'azione italiana costò agli inglesi, in termini di naviglio pesante messo fuori uso, come una battaglia navale perduta e fu tenuta per lungo tempo nascosta anche a causa della cattura degli equipaggi italiani che avevano effettuato la missione. La Valiant subì danni alla carena in un'area di 20 x 10 m a sinistra della torre A, con allagamento del magazzino munizioni A e di vari compartimenti contigui. Anche gli ingranaggi della stessa torre vennero danneggiati e il movimento meccanico impossibilitato, oltre a danni all'impianto elettrico. La nave dovette trasferirsi a Durban per le riparazioni più importanti che vennero effettuate tra il 15 aprile ed il 7 luglio 1942. Le caldaie e le turbine erano rimaste però intatte. La Queen Elizabeth invece fu squarciata sotto la sala caldaie B con una falla di 65 x 30 m che passava da dritta a sinistra, danneggiando l'impianto elettrico ed allagando anche i magazzini munizioni da 4,5", ma lasciando intatte le torri principali e secondarie. La nave riprese il mare solo per essere trasferita a Norfolk, in Virginia, dove rimase in riparazione per 17 mesi.

Per la prima volta dall'inizio del conflitto, la flotta italiana si trovava in netta superiorità rispetto a quella britannica, a cui non era rimasta operativa alcuna corazzata (la HMS Barham era stata a sua volta affondata da un sommergibile tedesco il 25 novembre 1941). La Mediterranean Fleet alla fine del 1941 disponeva solo di quattro incrociatori leggeri e alcuni cacciatorpediniere.

L'ammiraglio Cunningham per ingannare i ricognitori italiani decise di rimanere con tutto l'equipaggio a bordo dell'ammiraglia che, fortunatamente per lui, si era adagiata sul fondale poco profondo rimanendo in assetto orizzontale. Per mantenere credibile l'inganno nei confronti della ricognizione aerea, sulle navi si svolgevano regolarmente le cerimonie quotidiane, come l'alzabandiera. Poiché l'affondamento avvenne in acque basse le due navi da battaglia furono recuperate nei mesi successivi, ma la sconfitta rappresentò un colpo durissimo per la flotta britannica, che condizionò la strategia operativa anche ben lontano dal teatro operativo del Mediterraneo. A questo proposito, Churchill scrisse: “Tutte le nostre speranze di riuscire a inviare in Estremo Oriente delle forze navali dipendevano dalla possibilità d’impegnare sin dall’inizio con successo le forze navali avversarie nel Mediterraneo”.

Tuttavia contrasti tra gli Stati Maggiori dell'Asse non permisero di sfruttare questa grande occasione di conquistare il predominio aeronavale nel Mediterraneo e occupare Malta.

Come già detto, nella notte fra il 18 e il 19 dicembre 1941, sei uomini della X^, a cavallo di tre siluri a lenta corsa o “maiali”, forzano il porto ostile di Alessandria d’Egitto, affondano due grosse navi da battaglia inglesi, le corazzate Queen Elisabeth e Valiant, rispettivamente di 33.550 e 27.500 tonn., e danneggiano gravemente la cisterna Sagona e il caccia Jervis.

La preparazione dell’attacco venne condotta con la massima meticolosità, l’allenamento del personale pesantissimo e i materiali sempre all’avanguardia della tecnologia dell’epoca.

La notte del 3 dicembre il sommergibile Sciré comandato da Junio Valerio Borghese lasciò La Spezia per la missione GA3. Dopo uno scalo nell’Egeo, per imbarcare gli operatori dei mezzi d’assalto giunti sul posto dopo un trasferimento aereo dall’Italia, il 14 dicembre il sommergibile si diresse verso la costa egiziana per l’attacco previsto nella notte del 17. Una violenta mareggiata però fece ritardare l’azione di un giorno. I Marinai, operando in un ambiente non adatto alla natura umana come il mare, sono di per se superstiziosi e per questo alcuni ritengono che la missione fu posticipata anche per motivi scaramantici!

Alle 07:00 del 14 dicembre, quindi, imbarcati gli operatori, il battello lascia gli ormeggi e inizia la navigazione occulta verso Alessandria, emergendo solo di notte per ricaricare le batterie e verificare la rotta. La sera del 17 dicembre 1941 arriva la conferma della presenza in porto di due navi da battaglia da parte del Comando Centrale della Marina. L’ordine fu perentorio da parte di SUPERMARINA: "accertata presenza in porto due navi da battaglia. probabile portaerei: ATTACCATE”. Approntato lo Scirè inizia la sua incredibile corsa sottomarina attraverso gli sbarramenti minati e su fondali rapidamente decrescenti, per emergere, infine, in posizione perfetta a circa un miglio e mezzo a Nord del porto di Alessandria.

Assegnati i bersagli, i sei uomini del gruppo d’assalto, ripartiti in tre coppie, procedono verso la base nemica:

- sul maiale n°221, il tenente di vascello Luigi Durand De la Penne con il Capo Palombaro Emilio Bianchi;

- sul maiale n°222, il capitano del Genio Navale Antonio Marceglia con il Sottocapo Palombaro Spartaco Schergat;

- sul maiale n°223, il capitano delle Armi Navali Vincenzo Martellotta con il Capo Palombaro Mario Marino.

Questi valorosi uomini si avviano a compiere una impresa leggendaria nella storia della nostra Marina e in quella navale di tutti i tempi, affondando con le testate esplosive dei loro maiali Marceglia e Schergat la corazzata Queen Elizabeth (33.550 tonnellate), De La Penne e Bianchi la corazzata Valiant (27.500 tonnellate), e danneggiando, Martellotta e Marino la petroliera Sagona (7.750 t.) e il cacciatorpediniere Jervis (1.690 t).

L’azione italiana costò agli inglesi quanto una battaglia navale perduta e fu tenuta per lungo tempo nascosta, anche a causa della cattura degli equipaggi italiani che avevano effettuato la missione. Gli operatori misero a segno un’impresa epica e una straordinaria vittoria nei confronti di quella che era, all’epoca, la più forte Marina del mondo; cosa che indusse lo stesso primo ministro inglese Winston Churchill a scrivere: «Nel corso di alcune settimane l’intera flotta da battaglia nel Mediterraneo orientale è stata eliminata come forza combattente».

L’ammiraglio Cunningham, Comandante la Mediterrean Fleet, per ingannare i ricognitori italiani decise di rimanere con tutto l’equipaggio a bordo dell’ammiraglia che, fortunatamente per lui, si era adagiata sul fondale poco profondo rimanendo in assetto orizzontale. Per mantenere credibile l’inganno nei confronti della ricognizione aerea, sulle navi si svolgevano regolarmente le cerimonie quotidiane, come l’alzabandiera.

Poiché l’affondamento avvenne in acque basse le due navi da battaglia furono recuperate nei mesi successivi, ma la sconfitta rappresentò un colpo durissimo per la flotta britannica, che condizionò la strategia operativa anche ben lontano dal teatro operativo del Mediterraneo. Si dovrà attendere la seconda metà del 1942 per rivedere una Royal Navy credibile e operativa nel Mediterraneo.

A questo proposito, sempre Churchill scrisse:

«Tutte le nostre speranze di riuscire a inviare in Estremo Oriente delle forze navali dipendevano dalla possibilità d’impegnare sin dall’inizio con successo le forze navali avversarie nel Mediterraneo». «…sei italiani equipaggiati con materiali di costo irrisorio hanno fatto vacillare l’equilibrio militare in Mediterraneo a vantaggio dell’Asse…».

Nel 1944 tutti e 6 gli operatori della X^ Flottiglia MAS vennero decorati a Taranto con la Medaglia d’Oro al Valor Militare che venne appuntata, in segno di particolare onore, dal commodoro Sir Charles Morgan, ex comandante della HMS Valiant.

L’impresa di Alessandria rappresenta il suggello della tradizione dei Mezzi d’Assalto della Marina italiana.

Non tralasciando e non dimenticando:

- le gesta sul mare dei nostri antenati Etruschi;

- dei Romani;

- delle Repubbliche Marinare;

- e delle Marine Preunitarie;

- la nostra tradizione marinara al 13 agosto 1860 quando la Marina Garibaldina provò una incursione a Castellammare di Stabia per impadronirsi del vascello borbonico Monarca;

- Nella Guerra Italo-Turca vennero violate diverse basi ottomane. La più famosa fu compiuta a luglio del 1912 quando il Comandante Millo forzò i Dardanelli con 5 piccole torpediniere, mutando a favore dell’Italia il clima internazionale del momento;

- Nella Prima Guerra Mondiale la strategia dell’incursione navale, fu sostenuta dal Grande Ammiraglio Paolo Thaon di Revel e rappresentò la chiave di volta della vittoria finale;

- le tante azioni compiute dai nostri MAS e dai vari mezzi speciali quali il Grillo e Locusta e la Torpedine Semovente Rossetti denominata Mignatta;

- imprese quali la “Beffa di Buccari”,

- l’affondamento delle Corazzate nemiche Wien, Szent Istvan e Viribus Unitis, ancora oggi capisaldi della nostra storia memoria di come il coraggioso e lo spregiudicato impiego della sorpresa da parte di pochi valorosi uomini rappresenti un fattore determinante tattico e soprattutto strategico.

In previsione del secondo conflitto mondiale, vennero sviluppate e approfondite sia dal punto di vista tecnico che operativo le già sperimentate capacità incursionistiche con la notte di Alessandria: essa capovolse istantaneamente per molti mesi gli equilibri di forza italo-inglesi.

L’incursione della X^ Mas si basò sui quattro elementi basilari:

- la scelta del momento, sostenuto da una adeguata attività di intelligence;

- La segretezza assoluta;

- l’impiego dei migliori mezzi disponibili e del personale maggiormente addestrato;

- La conduzione fino all’estremo dell’operazione.

I Mezzi d’Assalto furono un vero e proprio elemento di potere navale, e il Comando Subacquei e Incursori della Marina rappresenta ancor’oggi un riferimento per tutte le elìte a livello europeo, NATO e mondiale.

IL MUSEO DI LA SPEZIA

Il Museo dedica una specifica sezione del suo rinnovato percorso espositivo intitolata “Uomini, imprese ed Eroi” ed all’evoluzione dei mezzi d’assalto della Marina Militare e al ricordo degli eroici operatori che compirono azioni memorabili come quella della di Alessandria.

La grande teca che accoglie il Siluro a Lenta Corsa – Maiale – catalizza gli sguardi dei visitatori e racconta gesta immortali di audacia e sprezzo del pericolo.

I mezzi d’assalto sviluppati nella seconda guerra mondiale dalla Regia Marina nascono allo scopo di riequilibrare il divario di potenziale che nel Mediterraneo vedeva contrapposta la Marina Britannica a quella Italiana. Il Siluro a Lenta Corsa è la massima espressione della tecnologia subacquea italiana dell’epoca: il progetto deriva dalla “mignatta” di Rossetti e Paolucci realizzata durante la prima guerra mondiale (il cui unico esemplare esistente è custodito al Museo Tecnico Navale della Spezia) e viene sviluppato da due ufficiali del Genio Navale, Teseo Tesei e Elios Toschi. Si tratta di un mezzo d’assalto subacqueo derivato dal corpo di un siluro modificato e reso pilotabile da due operatori in grado di condurlo in prossimità del bersaglio e posizionare una carica esplosiva – collocata nella testa del mezzo – al di sotto della carena della nave nemica.

Il progetto nasce a metà degli anni ’30, nel pieno della guerra d’Etiopia, in vista di un possibile allargamento europeo del conflitto. Scongiurato temporaneamente il pericolo, i progetti vengono accantonati per essere poi ripresi nel 1939 e portati avanti nella base segreta di Bocca di Serchio (LU). Il modello esposto al Museo appartiene alla 1a/2a serie realizzata nel 1940: il mezzo era mosso da un motore elettrico capace di una velocità massima di 3 nodi con un’autonomia di 15 miglia; per l’immersione era fornito di due “casse assetto”, una a prora ed una a poppa, esauribili da due pompe elettriche. La forza evocativa del modello esposto nasce dal mostrare anche gli operatori che lo conducevano: i due cavalcano “in tandem” il mezzo con davanti il pilota al riparo di una piccola carenatura atta a proteggere i comandi dei timoni di profondità e direzione, e i pochi ma fondamentali strumenti di navigazione (bussola, manometro di profondità, amperometro per la carica delle batterie). Di grande impatto nella ricostruzione proposta è anche l’attrezzatura subacquea originale impiegata dagli operatori per agire sotto la superficie del mare con la massima libertà di movimento e autonomia. Siamo di fronte a materiali frutto di studi pionieristici che testimoniano – se mai ve ne fosse ulteriore necessità – l’eccellenza tecnica raggiunta dalla Marina italiana.

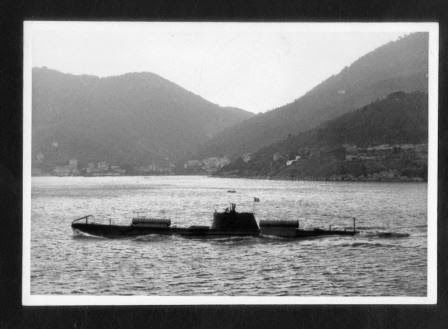

GLI AUTORESPIRATORI IN DOTAZIONE

L’auto respiratore ad ossigeno “A.R.O.”, venne sviluppato dal precedente modello Davis e migliorato da Angelo Belloni (ufficiale di Marina e sommergibilista): funzionava riciclando l’aria espirata dopo averla depurata con calce sodata – contenuta dentro il caratteristico sacco “polmone” sul petto dell’operatore – e arricchita con ossigeno contenuto nelle bombole sottostanti. Gli operatori indossano poi la tuta o vestito impermeabile “Belloni” (dal nome del suo ideatore), indumento protettivo indispensabile per affrontare le basse temperature dell’acqua durante le immersioni prolungate. Costituita da un materiale a doppio strato – internamente in gomma e esternamente in tela gommata impermeabile – copriva il corpo dai piedi fino al collo, con robuste cuciture di raccordo e stretti polsini in gomma. Nella stessa teca espositiva è visibile un modello del Sommergibile Scirè, altro protagonista della notte di Alessandria, con i tre caratteristici cilindri contenitori per il trasporto degli SLC ben visibili sul ponte di coperta. Lo Scirè ebbe il ruolo di mezzo “avvicinatore”, deputato a condurre i SLC e i loro operatori il più vicino possibile al porto obiettivo dell’attacco. Dopo l’eroica notte di Alessandria il comando del Sommergibile è affidato al Capitano di Corvetta Bruno Zelik e al mezzo viene assegnata una nuova e rischiosa missione: l’attacco al porto inglese di Haifa in Israele. Proprio in questa occasione l’avventurosa storia dello Scirè incontrerà il suo triste epilogo: scoperto dalla ricognizione aerea inglese viene colpito e affondato portando con sé tutto il suo equipaggio. Il Museo Tecnico Navale conserva alcuni cimeli recuperati nel 1984 dalla Marina Militare dal relitto del Sommergibile: esposti nel giardino sono visibili uno dei cilindri contenitori, un timone di profondità e il rostro tagliareti prodiero; all’interno, nel salone principale, una parte dello scafo recuperata dai fondali è stata ricostruita in forma di sacrario dedicato all’imperitura memoria dei Caduti dello Scirè.

Dopo l'armistizio

Dopo l'armistizio dell'8 settembre 1943, tutti e 6 gli operatori ad eccezione di Emilio Bianchi vennero rilasciati dai campi di prigionia alleati e rimpatriati in Italia, dove aderirono al Regno del Sud. Inquadrati in Mariassalto, nel marzo 1945 Luigi Durand de la Penne venne decorato a Taranto con la medaglia d'oro al valor militare appuntata, in segno di particolare onore, dal commodoro Sir Charles Morgan, ex comandante della HMS Valiant.

ENGLISH

In the Alexandria Enterprise, six men of the Regia Marina's 10th MAS Flotilla, aboard three underwater assault craft colloquially known as 'pigs' and technically slow-moving torpedoes (SLCs), penetrated the port of Alexandria and sank the two British battleships HMS Queen Elizabeth (33.550 t) and HMS Valiant (27.500 t) with explosive warheads, and also damaged the tanker Sagona (7.750 t) and the destroyer HMS Jervis (1.690 t).

What is undoubtedly the most famous of the actions of the 10th M.A.S. Flotilla, called Operation G.A. 3, was carried out on the night of December 18th-19th, 1941. It was a sort of revenge for the Italian armed forces after the serious naval losses suffered during the night of Taranto (November 1940) and projected the names of Borghese and his submarine, the Scirè, into legend.

Preparation

Preparation for the attack, as far as the Xth's operators were concerned, was carried out with the utmost meticulousness. The training of the personnel was very heavy, and the materials were always on the cutting edge. Information support, on the other hand, was not as good, especially with regard to the information provided by the SIM on the situation outside the port and for the escape plan.

The attack

On the night of December 3rd, the submarine Sciré, commanded by Lieutenant Junio Valerio Borghese, left La Spezia for the G.A.3 mission. After a stopover in Leros, in the Aegean Sea, to embark the operators of the assault craft which had arrived in the area after the air transfer from Italy, on December 14th the submarine headed towards the Egyptian coast for the attack planned for the night of the 17th.

On the night of the 18th, with optimal sea conditions, taking advantage of the arrival of three destroyers which forced the British to open a gap in the port's defences, the three SLCs (Slow Running Torpedoes), each piloted by two men (a crew chief and his dictionary), entered the base and headed towards their targets. The raiders had to get under the keel of their target, place the explosive charge and then leave the area, heading ashore and independently trying to reach the submarine that would be waiting for them a few days later off Rosetta.

The Durand de la Penne - Bianchi crew on the No. 221 pig headed for the battleship Valiant. Without the cooperation of the latter, who had fallen ill due to a respirator malfunction, de la Penne dragged his vehicle to the bottom, managing to place its explosive charge under the hull of the battleship before surfacing, being spotted, captured and taken right to the battleship. Soon after, the British also captured Bianchi, who had surfaced and clung to a battleship mooring buoy, and locked him in the same compartment below the waterline where they had taken Durand de la Penne, hoping to convince them to reveal the placement of the charges. At 05:30, half an hour after the explosion, de la Penne called the surveillance staff to be taken to the commander of the ship, Morgan, to inform him of the risk to the crew, but he had the Italian officer returned to where he was. At the scheduled time, the explosion ripped through the hull of the battleship, causing several compartments to flood and many others to be filled with smoke. The compartment housing the Italians was also affected by the explosion and a chain dislodged by the blast injured Durand De La Penne's head, but the two Italians managed to get out of the room and onto the deck where they were evacuated along with the rest of the crew.

Martellotta and Mario Marino, on No. 222, forced to sail on the surface due to the former's illness, led their attack on the tanker Sagona. This ship was a target assigned by Commander Borghese as a secondary objective, if he noticed that the aircraft carrier in force with the Mediterranean Fleet was not in port. After going ashore they were also captured by the Egyptians. Around six o'clock the next morning the explosions took place. Four ships were seriously damaged in the action: in addition to the three mentioned above, the destroyer HMS Jervis, moored alongside the Sagona, was also a victim of the charges laid by the Italian attackers.

Antonio Marceglia and Spartaco Schergat in a 'perfect mission', 'textbook' compared to those of the other operators, instead attacked the Queen Elizabeth, to which they attached the explosive warhead of their pig, then reached land and managed to get away from Alexandria, only to be captured the next day, due to the sloppiness with which the Italian military secret service, SIM, had prepared the escape: The divers were given banknotes that were no longer legal tender in Egypt and the crew lost time trying to change them. Despite the Italians' attempt to pass themselves off as French sailors belonging to the crew of one of the ships interned in the roadstead, they were recognised and captured.

The consequences:

"...six Italians equipped with ridiculously cheap materials have tipped the military balance in the Mediterranean to the advantage of the Axis..." Winston Churchill.

Although the action was a success, the ships lay on the bottom, and it was not immediately possible to be certain that they would not be able to return to sea. Nevertheless, the loss of life was very limited: only eight sailors lost their lives.

The Italian action cost the British, in terms of heavy shipping put out of action, as a lost naval battle and was kept under wraps for a long time also because of the capture of the Italian crews that had carried out the mission. The Valiant suffered hull damage in a 20 x 10 m area to the left of Tower A, with flooding of Ammunition Magazine A and several adjacent compartments. The gears of the same tower were also damaged and mechanical movement was prevented, as well as damage to the electrical system. The ship had to move to Durban for major repairs, which were carried out between 15 April and 7 July 1942. The boilers and turbines, however, remained intact. Queen Elizabeth was ripped apart under Boiler Room B with a 65 x 30 m hole running from starboard to port, damaging the electrical system and also flooding the 4.5" ammunition stores, but leaving the main and secondary towers intact. The ship resumed seaward only to be transferred to Norfolk, Virginia, where she remained in repair for 17 months.

For the first time since the beginning of the conflict, the Italian fleet was in clear superiority over the British fleet, which had no battleships left operational (HMS Barham had also been sunk by a German submarine on 25 November 1941). By the end of 1941, the Mediterranean Fleet had only four light cruisers and a few destroyers.

Admiral Cunningham, in order to deceive the Italian scouts, decided to remain with the entire crew aboard the flagship, which, fortunately for him, lay on the shallow water and remained in a horizontal position. To keep the deception of the air reconnaissance credible, daily ceremonies, such as the raising of the flag, took place regularly on the ships. Since the sinking took place in shallow waters, the two battleships were salvaged in the following months, but the defeat represented a heavy blow for the British fleet, which conditioned its operational strategy even far from the operational theatre of the Mediterranean. On this subject, Churchill wrote: 'All our hopes of succeeding in sending naval forces to the Far East depended on successfully engaging the opposing naval forces in the Mediterranean from the outset'.

However, disagreements between the Axis General Staff did not allow them to take advantage of this great opportunity to gain naval air dominance in the Mediterranean and occupy Malta.

As already mentioned, in the night between 18 and 19 December 1941, six men of the Regia Marina's X MAS Flotilla, astride three underwater assault craft, the slow-moving torpedoes, called in slang pigs, forced their way into the enemy port of Alexandria, sinking two large British battleships, the battleships Queen Elisabeth and Valiant, of 33,550 and 27,500 tons respectively, and seriously damaging the tanker Sagona and the destroyer Jervis.

The preparation of the attack was conducted with the utmost meticulousness, the training of the personnel was very heavy and the equipment was always at the cutting edge.

On the night of December 3rd, the submarine Sciré commanded by Lieutenant Junio Valerio Borghese left La Spezia for the GA3 mission.

After a stopover in Leros, in the Aegean Sea, to embark the operators of the assault craft which had arrived on the spot after an air transfer from Italy, on 14 December the submarine headed towards the Egyptian coast for the attack planned for the night of the 17th.

However, a violent sea storm delayed the action by one day. It is well known that sailors, operating in an environment not suited to human nature, are superstitious in themselves and for this reason there are those who claim that, in addition to the storm, the mission was also postponed for superstitious reasons!

At 07:00 on the 14th of December, therefore, having embarked the operators, the boat left its moorings and began its covert navigation towards Alexandria, emerging only at night to recharge its batteries and verify its course.

On the evening of December 17th, 1941, the Central Naval Command confirmed the presence of two battleships in port.

The order was peremptory: "FROM SUPERMARINA: two battleships found in the harbour. probable aircraft carrier: ATTACK".

Fully loaded with air and power, the Scirè began her incredible underwater run through the mined barrages and over rapidly diminishing seabeds, finally emerging in a perfect position about a mile and a half north of Alexandria Harbor (to be exact, 1.3 miles by 356° from the Alexandria light).

Once the targets had been assigned, the six men of the assault group, divided into three pairs, proceeded towards the enemy base: on pig n. 221, Lieutenant Luigi Durand De la Penne with Chief Diver Emilio Bianchi; on pig n. 222, Captain of the Naval Engineers Antonio Marceglia with Chief Diver Spartaco Schergat; on pig n. 223, Captain of the Naval Arms Vincenzo Martellotta with Chief Diver Mario Marino.

These brave men went on to perform a legendary feat in the history of our Navy and in the naval history of all time, sinking with the explosive warheads of their pigs Marceglia and Schergat the battleship Queen Elizabeth (33,550 tons), De La Penne and Bianchi the battleship Valiant (27,500 tons), and damaging, Martellotta and Marino the tanker Sagona (7750 tons) and the destroyer Jervis (1690 tons).

The Italian action cost the British as much as a lost naval battle and was kept hidden for a long time, also due to the capture of the Italian crews that had carried out the mission.

The operators pulled off an epic feat and an extraordinary victory over what was, at the time, the strongest navy in the world, prompting British Prime Minister Winston Churchill to write:

"In the course of a few weeks the entire battle fleet in the eastern Mediterranean has been eliminated as a fighting force".

Admiral Cunningham, Commander of the Mediterrean Fleet, in order to deceive the Italian scouts, decided to remain with his entire crew aboard the flagship which, fortunately for him, lay on the shallow water and remained horizontal. In order to keep the deception of the aerial reconnaissance credible, daily ceremonies, such as the raising of the flag, took place regularly on the ships.

Since the sinking occurred in shallow waters, the two battleships were salvaged in the following months, but the defeat was a severe blow to the British fleet, which conditioned its operational strategy even far from the operational theatre of the Mediterranean. We will have to wait until the second half of 1942 to see a credible and operational Royal Navy in the Mediterranean.

In this regard, Churchill wrote: 'All our hopes of succeeding in sending naval forces to the Far East depended on the possibility of successfully engaging the adversary's naval forces in the Mediterranean from the outset'.

"...six Italians equipped with ridiculously cheap equipment tipped the military balance in the Mediterranean to the Axis' advantage..." (Winston Churchill).

In 1944, all six operators of the X MAS Flotilla were decorated in Taranto with the Gold Medal for Military Valour, which was pinned on them, as a sign of special honour, by Commodore Sir Charles Morgan, former commander of HMS Valiant.

The Alexandria feat represents the seal on the Italian Navy's Assault Craft tradition. An ancient tradition that - leaving aside, but not forgetting, the exploits on the sea of our Etruscan, Roman, Maritime Republics and Pre-Unitarian Marines ancestors - can be traced back to 13th August 1860 when the Garibaldian Navy, intent on operations to unify Italy, attempted a raid on Castellammare di Stabia to seize the Bourbon vessel Monarca.

In the Italian-Turkish War, several Ottoman bases were breached. The most famous was in July 1912 when Commander Millo forced the Dardanelles with five small torpedo boats, changing the international climate in Italy's favour at the time.

In the Great War, the strategy of naval incursion, supported by Grand Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel, was the key to the final victory. We remember the many actions carried out by our MAS and the various special vehicles such as the Grillo and Locusta and the Rossetti self-propelled torpedo boat called Mignatta. Feats such as the "Beffa di Buccari" (Buccari hoax), and the sinking of the enemy battleships Wien, Szent Istvan and Viribus Unitis are still landmarks in our naval history, reminding us of how the courageous and unscrupulous use of surprise by a few brave men was a determining factor both tactically and strategically.

Later, in anticipation of the Second World War, in which our Navy would have to face the most powerful navy in the world at the time, the Mediterrean Fleet, these pre-eminent raiding capabilities were developed and deepened both technically and operationally.

The Night of Alexandria turned the balance in the Mediterranean upside down. It was based on the four basic elements of the naval incursion: the choice of the moment, supported by adequate intelligence activity; absolute secrecy; the use of the best available means and the best trained personnel; and the conduct of the operation to the extreme.

The myth of the great naval battle resolving a conflict had once again been disproved.

As Admiral Spigai commented in an article in the March 1961 Maritime Review, "... the Strike Force was a real element of naval power...".

This is why COMSUBIN (the Comando Subacquei e Incursori della Marina) is still a world-class and elite reference point.

The La Spezia Naval Technical Museum

The Museum dedicates a specific section of its renewed exhibition itinerary - significantly entitled "Men, enterprises and heroes" - to the evolution of the Navy's assault craft and the memory of the heroic operators who carried out memorable actions such as the "night of Alexandria”. The large display case that houses the "Siluro a Lenta Corsa - Maiale" (Slow Running Torpedo - Pig) catches the visitor's eye and recounts immortal feats of daring and reckless disregard for danger. The assault craft developed by the Regia Marina during the Second World War were created to balance the potential gap between the British and Italian navies in the Mediterranean. The Lenta Corsa torpedo is the ultimate expression of Italian underwater technology of the period: the design derives from Rossetti and Paolucci's "mignatta" built during the First World War (the only surviving example of which is housed in La Spezia's Naval Technical Museum) and was developed by two Naval Engineers, Teseo Tesei and Elios Toschi. It is an underwater assault craft derived from a modified torpedo body that can be piloted by two operators capable of driving it close to the target and placing an explosive charge - placed in the head of the craft - under the hull of the enemy ship. The project was conceived in the mid-1930s, at the height of the Ethiopian war, in view of a possible European extension of the conflict. When the danger was temporarily averted, the projects were shelved and then resumed in 1939 and continued in the secret base of Bocca di Serchio (LU). The model on display at the Museum belongs to the 1st/2nd series built in 1940: the craft was powered by an electric motor capable of a maximum speed of 3 knots with a range of 15 miles; for diving it was equipped with two "buoyancy tanks", one at the bow and one at the stern, which could be filled by two electric pumps. The evocative power of the model on display comes from the fact that it also shows the operators who drove it: the two of them ride "in tandem" on the boat, with the pilot in front, protected by a small fairing protecting the depth and direction rudder controls, and the few but fundamental navigation instruments (compass, depth gauge, ammeter for battery charging). Also of great impact in the proposed reconstruction is the original underwater equipment used by the operators to operate below the surface of the sea with maximum freedom of movement and autonomy. These materials are the result of pioneering studies that testify - if ever there was further need - to the technical excellence achieved by the Italian Navy.

SELF-CONTAINED BREATHING APPARATUS

The self-contained oxygen breathing apparatus (A.R.O.), developed from the earlier Davis model and improved by Angelo Belloni (a naval officer and submariner), worked by recycling exhaled air after it had been purified with soda lime - contained inside the characteristic "lung" bag on the operator's chest - and enriched with oxygen contained in the cylinders below. The operators then wear the "Belloni" suit or waterproof suit (named after its creator), an indispensable protective garment for dealing with low water temperatures during prolonged dives. Made of a double-layered material - internally in rubber and externally in waterproof rubberized canvas - it covered the body from the feet up to the neck, with strong connecting seams and narrow rubber cuffs.

In the same display case is a model of the Submarine Scirè, another protagonist of the night of Alexandria, with the three characteristic container cylinders for transporting SLCs clearly visible on the deck. The Scirè acted as an "approaching" submarine, responsible for bringing the SLCs and their operators as close as possible to the target port. After the heroic night in Alexandria, the command of the submarine was entrusted to Lieutenant Commander Bruno Zelik and the boat was assigned a new and risky mission: the attack on the British port of Haifa in Israel. It was on this occasion that the Scirè's adventurous story met its sad epilogue: discovered by British aerial reconnaissance, it was hit and sunk, taking its entire crew with it. The Naval Technical Museum houses a number of relics recovered in 1984 by the Italian Navy from the wreck of the submarine: on display in the garden are one of the container cylinders, a depth rudder and the forward cutter rostrum; inside, in the main hall, a part of the hull recovered from the seabed has been reconstructed in the form of a shrine dedicated to the everlasting memory of the Scirè's victims.

After the armistice

After the armistice of 8 September 1943, all six operators except Emilio Bianchi were released from Allied prison camps and repatriated to Italy, where they joined the Kingdom of the South. In March 1945, Luigi Durand de la Penne was decorated in Taranto with the Gold Medal for Military Valour, awarded as a token of special honour by Commodore Sir Charles Morgan, former commander of HMS Valiant.

(Web, Google, Wikipedia, giornidistoria, You Tube)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento

Nota. Solo i membri di questo blog possono postare un commento.