Il Fairey Rotodyne era un prototipo di autogiro composito o "rotodina" sperimentale con rotore tip jet sviluppato dall'azienda aeronautica britannica Fairey Aviation Company Limited negli anni cinquanta. Il Rotodyne era in altri termini una girodina da trasporto passeggeri. Per la sua peculiare configurazione, viene talvolta indicato anche come Girodina o elicottero composito.

Nonostante l'interesse suscitato all'epoca e gli ordini iniziali ricevuti, lo sviluppo di questo interessante prototipo venne rallentato e infine arrestato dalla fusione tra la Fairey e la Westland Aircraft.

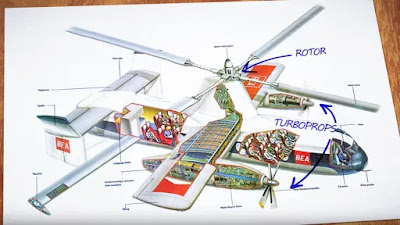

Il Fairey Rotodyne era un autogiro composto britannico degli anni '50 progettato e costruito da Fairey Aviation e destinato ad usi commerciali e militari. Uno sviluppo del precedente Gyrodyne aveva stabilito un record mondiale di velocità per elicotteri: il Rotodyne; presentava un rotore alimentato da un getto alle estremità delle pale del rotore che bruciava una miscela di carburante e aria compressa emessa da due turbopropulsori Napier Eland montati sull'ala. Il rotore veniva azionato per i decolli verticali, gli atterraggi e il volo stazionario, nonché per il volo traslazionale a bassa velocità e ruotava automaticamente durante il volo di crociera con tutta la potenza del motore applicata a due eliche.

Fu costruito un prototipo e, sebbene il Rotodyne fosse promettente nel concetto e avesse avuto successo nelle prove, il programma alla fine fu annullato. La risoluzione venne attribuita alla tipologia non riuscendo ad attirare eventuali ordini commerciali; ciò era in parte dovuto alle preoccupazioni per gli alti livelli di rumore generato in volo del getto alle estremità dei rotori. Anche la politica ebbe un ruolo nella mancanza di ordini da parte del governo.

Sviluppo

Dalla fine degli anni '30 in poi, furono compiuti notevoli progressi in un campo completamente nuovo dell’aeronautica: i velivoli ad ala rotante. Sebbene alcuni progressi in Gran Bretagna fossero stati compiuti prima dello scoppio della seconda guerra mondiale, le priorità in tempo di guerra vennero assegnate all'industria aeronautica; lo sviluppo di aeromobili ed elicotteri venne emarginato. Nell'immediato clima del dopoguerra, la Royal Air Force (RAF) e la Royal Navy decisero di acquisire elicotteri sviluppati in America: i Sikorsky R-4 e Sikorsky R-6, conosciuti localmente come Hoverfly I e Hoverfly II rispettivamente. L’esperienza derivante dal funzionamento di questi aeromobili, insieme al vasto esame che fu condotto sui prototipi di elicotteri tedeschi catturati, stimolò un notevole interesse all'interno delle FF.AA. e dell'industria per lo sviluppo in GB di aeromobili avanzati.

La Fairey Aviation era una di queste società che fu spinta dal potenziale dei velivoli ad ala rotante e sviluppò il Fairey FB-1 Gyrodyne in conformità con la specifica E.16 / 47. Il Gyrodyne era un velivolo unico nel suo genere che definiva un terzo tipo di velivolo a rotore, inclusi autogiro ed elicottero. Avendo poco in comune con il successivo Rotodyne, era caratterizzato dal suo inventore, il dott. JAJ Bennett, già direttore tecnico della società Cierva Autogiro prima della seconda guerra mondiale come velivolo intermedio progettato per combinare la sicurezza e la semplicità dell'autogiro con le prestazioni in volo stazionario. Il suo rotore era azionato in tutte le fasi del volo con il passo collettivo che è una funzione automatica della coppia dell'albero, con un'elica montata lateralmente che forniva sia la spinta per il volo in avanti che la correzione della coppia del rotore. Il 28 giugno 1948, l'FB-1 dimostrò il suo potenziale durante i voli di prova quando raggiunse il record mondiale di velocità, raggiungendo una velocità registrata di 124,3 mph (200,0 km/h). Tuttavia, il programma non fu esente da problemi: un incidente mortale coinvolse uno dei prototipi; si verificò nell'aprile 1949 a causa di un difetto di lavorazione di un dado di ritegno del collegamento di una pala del rotore. Il secondo FB-1 venne modificato per studiare un rotore a getto di punta con propulsione fornita da eliche montate sulla punta di ogni stub wing e fu ribattezzato Jet Gyrodyne.

Fra il 1951 e il 1952, il British European Airways (BEA) formulò internamente un requisito per un rotorcraft per il trasporto di passeggeri, comunemente indicato come Bealine-Bus o BEA Bus: doveva essere un rotorcraft plurimotore in grado di servire come aereo di linea a corto raggio; la BEA intendeva farlo volare tra le principali città e doveva trasportare un minimo di 30 passeggeri per essere economico; desideroso di sostenere l'iniziativa, il Ministero dell'approvvigionamentoha sponsorizzò una serie di studi di progettazione da condurre a sostegno del requisito della BEA. Sia gli organismi civili che quelli governativi avevano previsto la necessità di tali aeromobili ed avevano considerato solo una questione di tempo prima che diventassero comuni nella rete di trasporto britannica.

Il requisito BEA Bus fu soddisfatto con una varietà di proposte avveniristiche; osservazioni pratiche e apparentemente poco pratiche furono presentate da numerosi produttori. Tra questi, la Fairey che aveva anche scelto di presentare i suoi progetti e di partecipare per soddisfare il requisito con un design particolare: era il Fairey “Rotordyne".

La Fairey aveva progettato molteplici disposizioni e configurazioni per il velivolo variando i propulsori utilizzati e la capacità interna; l'azienda presentò la sua prima domanda al Ministero il 26 gennaio 1949. Entro due mesi, Fairey aveva prodotto altre tre proposte alternative, incentrate sull'uso di motori come il Rolls-Royce Dart e l'Armstrong Siddeley Mamba. Nell'ottobre 1950 fu assegnato un contratto iniziale per lo sviluppo di un rotorcraft a quattro pale da 16.000 libbre. Il progetto Fairey venne notevolmente rivisto nel corso degli anni, e ricevette finanziamenti governativi per sostenerne lo sviluppo.

All'inizio dello sviluppo, Fairey scoprì che garantire l'accesso ai motori per alimentare il suo design era difficile. Nel novembre 1950, il presidente della Rolls-Royce, Lord Hives, protestò dicendo che le risorse di progettazione della sua azienda erano troppo limitate su più progetti; di conseguenza, il motore Dart inizialmente selezionato fu sostituito dal motore Mamba della società rivale Armstrong Siddeley. Nel luglio 1951, la Fairey ripresentò proposte utilizzando il motore Mamba in layout a due e tre motori, supportando pesi totali di 20.000 libbre (9,1 t) e 30.000 libbre (14 t) rispettivamente; la configurazione adottata per accoppiare il motore Mamba ai compressori ausiliari era nota come Cobra. A causa delle lamentele della Armstrong Siddeley sulla mancanza di risorse, la Fairey propose anche l'uso alternativo di motori come il de Havilland Goblin e il turbogetto Rolls-Royce Derwent per azionare le eliche anteriori.

La Fairey non godeva tuttavia di un rapporto positivo con la de Havilland, e così scelse di rivolgersi a D. Napier & Son e al suo motore turboalbero Eland nell'aprile del 1953. Dopo la selezione dell'Eland, il design di base dell'aereo a rotore, noto come il Rotodyne Y, fu messo a punto: era alimentato da una coppia di motori Eland N.El.3 forniti di compressori ausiliari e di un rotore principale a quattro pale di grande sezione, con un peso totale previsto di 33.000 libbre. Allo stesso tempo, un fu proposta anche la versione ingrandita, designata come Rotodyne Z, equipaggiata con motori Eland N.El.7 più potenti e un peso totale di 39.000 libbre.

Contratto

Nell'aprile 1953, il Ministero delle forniture contrattò per la costruzione di un unico prototipo del Rotodyne Y, alimentato dal motore Eland, successivamente designato con il numero di serie XE521, per scopi di ricerca. Come da contratto, il Rotodyne sarebbe stato il più grande elicottero da trasporto del suo tempo, con una capienza massima di 40-50 passeggeri, pur possedendo una velocità di crociera di 150 mph e un'autonomia di 250 miglia nautiche. La Fairey aveva stimato che 710.000 sterline avrebbero coperto i costi di produzione della cellula. Nell'ottica di un velivolo che avrebbe incontrato l'approvazione normativa nel più breve tempo possibile, i progettisti della Fairey lavorarono per soddisfare i requisiti di aeronavigabilità civile sia per gli elicotteri che per i bimotori di dimensioni simili. Un modello senza rotore in scala fu ampiamente testato in galleria del vento per le prestazioni ad ala fissa. Un modello più piccolo (scala 1/15) con un rotore alimentato venne utilizzato per le indagini di downwash.

Durante la costruzione del prototipo, i finanziamenti per il programma si arrestarono. I tagli alla spesa per la difesa indussero il Ministero della Difesa a ritirare il proprio sostegno, facendo gravare su ogni possibile cliente civile l'onere dei costi. Il governo accettò di mantenere i finanziamenti per il progetto solo se, tra le altre qualifiche, Fairey e Napier (attraverso la loro società madre English Electric) avessero contribuito rispettivamente ai costi di sviluppo del motore Rotodyne ed Eland. A seguito di disaccordi con la Fairey su questioni politiche, il dottor Bennett lasciò l'azienda per unirsi alla Hiller Helicopters in California; la responsabilità per lo sviluppo della Rotodyne fu assunta dal dottor George S Hislop, che divenne l'ingegnere capo dell'azienda.

La fabbricazione della fusoliera, delle ali e dell'assemblaggio del rotore del prototipo fu condotta presso lo stabilimento di Fairey a Hayes, Hillingdon, West London, mentre la costruzione dell'assemblaggio della coda fu eseguita presso lo stabilimento dell'azienda a Stockport, Greater Manchester e l'assemblaggio finale venne eseguito a White Waltham Campo d'aviazione, Maidenhead. Inoltre, un banco di prova statico a grandezza naturale venne assemblato presso la RAF Boscombe Down per supportare il programma; l'impianto statico presentava un rotore e un propulsore completamente operativi che fu provato in più occasioni, incluso un test di approvazione di 25 ore per il Ministero.

Mentre era in corso la costruzione del primo prototipo, le prospettive per il Rotodyne apparivano positive; secondo Wood, c'era interesse per il tipo sia da parte civile che militare.

La BEA stava monitorando con interesse l'avanzamento del programma; esteriormente ci si aspettava che la compagnia aerea effettuasse un ordine poco dopo l'emissione di un ordine per una versione militarizzata dell'aereo a rotore. Anche la società americana Kaman Helicopters mostrò un forte interesse per il progetto per averlo studiato da vicino poiché l'azienda considerava il potenziale per la produzione su licenza del Rotodyne sia per i clienti civili che militari.

A causa dell'interesse dell'esercito e della RAF, per un certo periodo lo sviluppo della Rotodyne fu finanziato dal bilancio della difesa. Durante il 1956, il Defence Research Policy Committee dichiarò che non vi era alcun interesse militare per il modello, il che portò rapidamente la Rotodyne a fare affidamento esclusivamente sui bilanci civili come velivolo di ricerca / prototipo civile.

Dopo una serie di proposte e contrattazioni, nel dicembre 1956, HM Treasury autorizzò il proseguimento dei lavori sia sul motore Rotodyne che su quello Eland fino alla fine di settembre 1957. Tra le richieste del Tesoro era previsto che l'aereo doveva essere un successo tecnico e doveva acquisire una ditta ordine da BEA; sia Fairey che English Electric. Anche la società madre di Napier dovette assumersi una parte dei costi per il suo sviluppo.

Test e valutazione

Il 6 novembre 1957, il prototipo eseguì il suo primo volo, pilotato dal capo pilota collaudatore di elicotteri Capo dello squadrone W. Ron Gellatly e dall'assistente capo pilota collaudatore di elicotteri il tenente comandante John GP Morton come secondo pilota. Il primo volo era stato originariamente progettato per avvenire nel 1956; tuttavia, il ritardo era visto come inevitabile con un concetto completamente nuovo come quello utilizzato dal Rotodyne.

Il 10 aprile 1958, il Rotodyne raggiunse il suo primo passaggio di successo dal volo verticale all'orizzontale e poi di nuovo al volo verticale. Il 5 gennaio 1959, il Rotodyne stabilì un record mondiale di velocità nella categoria dei convertiplani, a 190,9 mph (307,2 km / h), su un circuito chiuso di 60 miglia (100 km). Oltre ad essere veloce, il rotorcraft aveva una caratteristica di sicurezza: poteva librarsi con un motore spento. Il prototipo mostrò diversi atterraggi in modalità autogiro. Il prototipo venne presentato più volte agli spettacoli aerei di Farnborough e Parigi: gli spettatori restavano increduli. In un caso, sollevò persino un ponte di travi di 100 piedi.

L'azionamento alle estremità delle pale del Rotodyne e il rotore scarico resero le sue prestazioni di gran lunga migliori rispetto agli elicotteri e ad altre forme di "convertiplani". Il velivolo poteva essere pilotato a 175 nodi (324 km / h) e trascinato in una virata in salita ripida senza dimostrare alcuna caratteristica di manovrabilità avversa.

In tutto il mondo cresceva l'interesse per la prospettiva del trasporto diretto da città a città. Il mercato del Rotodyne era quello di un "bus volante" di medio raggio: decollava verticalmente da un eliporto del centro città, con tutta la portanza proveniente dal rotore, e poi aumentava la velocità, eventualmente e la massima potenza dai motori veniva trasferita alle eliche con il rotore autorotating. In questa modalità, il passo collettivo, e quindi la resistenza del rotore poteva essere ridotta, poiché le ali assorbivano fino alla metà del peso del convertiplano. Il Rotodyne poteva andare quindi in crociera a una velocità di circa 150 nodi (280 km/ h) verso un'altra città, ad esempio da Londra a Parigi, dove poteva atterrare verticalmente nel centro della città. Quando il Rotodyne atterrò e il rotore smise di muoversi, le sue pale si abbassarono dal mozzo. Per evitare di colpire gli stabilizzatori verticali all'avvio, le punte di queste pinne venivano inclinate verso il basso rispetto all'orizzontale. Venivano sollevate una volta che il rotore era avviato.

Nel gennaio 1959, British European Airways (BEA) annunciò di essere interessata all'acquisto di sei aeromobili, con una possibilità fino a 20, ed emise una lettera di intenti che lo dichiarava, a condizione che tutti i requisiti, compresi i livelli di rumore, fossero soddisfatti. La Royal Air Force (RAF) emise un ordine per 12 versioni del trasporto militare. Venne firmata una lettera di intenti per l'acquisto di cinque a $ 2 milioni ciascuno, con un'opzione di altri 15 seppur con qualifiche, dopo aver calcolato che un Rotodyne più grande avrebbe potuto operare a metà del costo degli elicotteri; tuttavia, i costi unitari furono ritenuti troppo alti per tratte molto brevi da 10 a 50 miglia, e il Civil Aeronautics Board si oppose a velivoli ad ala fissa in competizione con le rotte più lunghe. La Japan Air Lines, che aveva inviato una squadra in Gran Bretagna per valutare il prototipo Rotodyne, dichiarò che avrebbe sperimentato il Rotodyne tra l' aeroporto di Tokyo e la città stessa, ed era interessata a usarlo anche sulla rotta Tokyo - Osaka .

Secondo alcune indiscrezioni, anche l’US ARMY era interessato all'acquisto di circa 200 Rotodynes. La Fairey desiderava ottenere i finanziamenti dal programma americano, ma non riuscì a persuadere la RAF ad ordinare il minimo necessario di 25 aeromobili necessari; a un certo punto, l'azienda considerò persino di fornire un singolo Rotodyne alla Eastern Airlines tramite la Kaman Helicopters, licenziataria statunitense della Fairey, in modo che potesse essere preso in esame dall'esercito americano per le prove. Tutti i Rotodynes destinati ai clienti statunitensi dovevano essere prodotti da Kaman a Bloomfield, nel Connecticut.

Il finanziamento del governo venne nuovamente garantito a condizione che gli ordini fermi fossero stati ottenuti dalla BEA. Gli ordini civili dipendevano dal fatto che i problemi di rumore venissero rispettati in modo soddisfacente; l'importanza di questo fattore portò la Fairey a sviluppare 40 diversi soppressori di rumore entro il 1955. Nel dicembre 1955, il dottor Hislop si disse certo che il problema del rumore potesse essere "eliminato". Secondo Wood, i due problemi più seri rilevati con il Rotodyne durante i test di volo erano il problema del rumore e il peso del sistema del rotore, quest'ultimo essendo 2.233 libbre sopra la proiezione originale di 3.270 libbre.

Problemi e annullamento

Nel 1959, il governo britannico, cercando di tagliare i costi, decretò che il numero di compagnie aeree dovesse essere abbassato e stabilì le sue aspettative per le fusioni in compagnie di aerei e motori aeronautici. Ritardando o negando l'accesso ai contratti di difesa, le imprese britanniche potevano essere costrette a fusioni; Duncan Sandys, Ministro dell'Aviazione, ribadì questa politica alla Fairey e fece sapere che il prezzo del continuo sostegno del governo per il Rotodyne sarebbe stato che Fairey si ritirasse virtualmente da tutte le altre iniziative nel campo dell'aviazione. Alla fine, Saunders-Roe e la divisione elicotteri della Bristol furono incorporate con la Westland. Nel maggio 1960, Fairey Aviation venne rilevata anche dalla Westland. A questo punto, il Rotodyne aveva trasportato quasi 1.000 persone per 120 ore in 350 voli e condotto un totale di 230 transizioni tra elicottero e autogiro, senza incidenti.

Nel 1958, il Tesoro ribadì la sua opposizione ad ulteriori finanziamenti per il programma. La questione fu inoltrata ad Harold Macmillan, l'allora Primo Ministro, che scrisse ad Aubrey Jones, il Ministro degli approvvigionamenti, il 6 giugno 1958, affermando che "questo progetto non doveva essere lasciato morire". Notevole importanza fu data alla BEA che sosteneva la Rotodyne mediante l'emissione di ordini; tuttavia, la compagnia aerea rifiutò di acquisire l'aeromobile fino a quando non fosse stata convinta che fossero state fornite garanzie sui criteri di prestazioni, economia e rumore. Poco dopo la fusione della Fairey con la Westland, a quest'ultima venne emesso un contratto di sviluppo da 4 milioni di sterline per il Rotodyne, che avrebbe dovuto vedere il modello entrare in servizio con la BEA.

Con il procedere dei test di volo con il prototipo Rotodyne, la Fairey era diventato sempre più insoddisfatta della Napier e del motore Eland poiché i progressi per migliorare quest'ultimo erano stati inferiori alle aspettative. Per ottenere il modello allungato a 48 posti del Rotodyne, sarebbe stato necessario l'Eland N.E1.7 da 3.500 ehp potenziato; dei 7 milioni di sterline stimati necessari per produrre l'aereo più grande, 3 milioni di sterline sarebbero stati destinati ai suoi motori.

La BEA era particolarmente favorevole ad un aereo più grande, potenzialmente in grado di ospitare fino a 66 passeggeri, il che avrebbe richiesto uno stanziamento di denaro ancora maggiore. La Fairey stava già lottando per ottenere le prestazioni dichiarate del motore Eland e aveva fatto ricorso a una miscela di carburante più ricca per ottenere la potenza necessaria; un effetto collaterale era quello di aggravare ulteriormente il notevole problema di rumore e ridurre l'efficienza del carburante. Non essendo in grado di risolvere i problemi con l'Eland, la Fairey optò per l'adozione del motore turboelica Rolls-Royce Tyne rivale per alimentare il Rotodyne Z più grande, sviluppato per ospitare da 57 a 75 passeggeri e, se equipaggiato con i motori Tyne (5.250 shp / 3.910 kW), avrebbe avuto una velocità di crociera prevista di 200 kn (370 km / h). Sarebbe stato in grado di trasportare quasi 8 tonnellate di merci; i carichi avrebbero potuto includere alcuni veicoli dell'esercito britannico e persino la fusoliera di alcuni aerei da combattimento. Sarebbe stato anche in grado di trasportare esternamente grandi carichi come una gru aerea, inclusi veicoli e interi aerei. Secondo alcune delle proposte successive, il Rotodyne Z avrebbe avuto un peso lordo di 58.500 libbre, un diametro del rotore esteso di 109 piedi e un'ala rastremata con un'apertura di 75 piedi.

Tuttavia, anche i motori Tyne erano sotto-potenziati per il design più grande. Il ministero dell'approvvigionamento si era impegnato a finanziare il 50% dei costi di sviluppo sia per il Rotodyne Z che per il modello del motore Tyne. Nonostante gli strenui sforzi della Fairey per ottenere il suo sostegno, l'ordine atteso dalla RAF non si concretizzò poiché il servizio era concentrato a quel tempo nell'affrontare efficacemente la questione della deterrenza nucleare. Man mano che le prove continuavano, sia i costi associati che il peso del Rotodyne continuavano a salire; il problema del rumore persisteva, anche se, secondo Wood: "c'erano segnali che i silenziatori l'avrebbero successivamente ridotto a un livello accettabile".

Sebbene i costi di sviluppo fossero condivisi per metà e metà tra la Westland e il governo, l'azienda stabilì che avrebbe ancora bisogno di ulteriori 9 milioni di sterline per completare lo sviluppo e raggiungere la produzione. A seguito dell'emissione di una richiesta al governo britannico per 18 Rotodynes di produzione, 12 per la RAF e 6 per BEA, il governo rispose negativamente per motivi economici. Di conseguenza, il 26 febbraio 1962, il finanziamento ufficiale per il Rotodyne fu interrotto. La conclusione finale del progetto arrivò quando la BEA scelse di rifiutare l’ordine per il Rotodyne, principalmente a causa delle sue preoccupazioni riguardo al problema del rumore. La direzione aziendale della Westland stabilì quindi che l'ulteriore sviluppo del Rotodyne verso lo stato di produzione non valeva l'investimento richiesto. Così terminarono tutti i lavori sul primo aeromobile da trasporto militare / civile a decollo verticale al mondo.

Dopo che il programma fu terminato, il prototipo Rotodyne stesso, che era proprietà del governo, fu smantellato e in gran parte distrutto. Un singolo vano della fusoliera, più i rotori e l'albero della testa del rotore sono sopravvissuti e sono in mostra al The Helicopter Museum, Weston-super-Mare.

Analisi

L'unica grande critica al Rotodyne era il rumore prodotto dai getti di punta delle pale; tuttavia, i jet funzionavano alla piena potenza solo per pochi minuti durante la partenza e l'atterraggio e, in effetti, il pilota collaudatore Ron Gellatly effettuò due voli sul centro di Londra e diversi atterraggi e partenze all'eliporto di Battersea senza reclami, sebbene John Farley, capo pilota collaudatore dell'Hawker Siddeley Harrier abbia successivamente commentato:

“Da due miglia di distanza avrebbe interrotto una conversazione. Voglio dire, il rumore di quei piccoli getti sulle punte del rotore era semplicemente indescrivibile. Allora cosa abbiamo? Il veicolo più rumoroso che il mondo abbia mai inventato lo fermerei nel mezzo di una città?”

Era in corso un programma di riduzione del rumore che era riuscito a ridurre il livello di rumore da 113 dB al livello desiderato di 96 dB da 600 piedi (180 m) di distanza, meno del rumore prodotto da un treno della metropolitana di Londra, e al momento dell'annullamento, erano in fase di sviluppo silenziatori che avrebbero ridotto ulteriormente il rumore - con 95 dB a 200 ft "previsti", la limitazione essendo il rumore creato dal rotore stesso. Questo sforzo, tuttavia, fu insufficiente per la BEA che, come espresso dal presidente Sholto Douglas, "non avrebbe acquistato un aereo che non poteva essere utilizzato a causa del rumore", e la compagnia aerea si rifiutò di ordinare il Rotodyne, che a sua volta bloccò il progetto.

Solo di recente che l'interesse è stato ristabilito nel trasporto diretto da città a città, con aeromobili come l' AgustaWestland AW609 e il CarterCopter/PAV. L'elicottero sperimentale Eurocopter X3 del 2010 condivide la configurazione generale del Rotodyne, ma è molto più piccolo. Un certo numero di design innovativi sono ancora in fase di studio per sviluppi futuri.

Design

Il Fairey Rotodyne era un grande rotorcraft ibrido, noto come autogiro composto o Gyrodyne. Secondo Wood, era "il più grande elicottero da trasporto dei suoi tempi". Presentava una fusoliera rettangolare aperta, in grado di ospitare da 40 a 50 passeggeri; un paio di porte a doppio guscio erano collocate sul retro della cabina principale in modo che le merci e persino i veicoli potessero essere caricati e scaricati.

Il Rotodyne aveva un grande rotore a quattro pale e due turboprop Napier Eland NEL3, uno montato sotto ciascuna delle ali fisse. Le pale del rotore erano un profilo alare simmetrico attorno a un longherone portante. Il profilo alare era realizzato in acciaio e lega leggera a causa delle preoccupazioni del centro di gravità. Allo stesso modo, il longherone era formato da uno spesso blocco di acciaio lavorato nella parte anteriore e una sezione più sottile più leggera formata da acciaio piegato e rivettato nella parte posteriore. L'aria compressa veniva convogliata attraverso tre tubi d'acciaio all'interno delle pale rotore. Le camere di combustione a getto di punta erano composte da Nimonic 80, complete di rivestimenti realizzati da Nimonic 75.

Per il decollo e l'atterraggio, il rotore era azionato da getti alle estremità delle pale. L'aria era prodotta dai compressori azionati tramite una frizione dai motori principali. Questo veniva alimentato attraverso canalizzazioni nel bordo d'attacco delle ali e fino alla testa del rotore. Ogni motore forniva aria per una coppia di rotori opposti; l'aria compressa veniva miscelata con carburante e bruciata. Essendo un sistema a rotore senza torsione, non era richiesto alcun sistema di correzione anti-coppia, sebbene il passo dell'elica fosse controllato dai pedali del timone per il controllo dell'imbardata a bassa velocità. Le eliche fornivano la spinta per il volo di traslazione mentre il rotore ruotava automaticamente. I controlli della cabina di pilotaggio includevano una leva del passo ciclico e collettivo, come in un elicottero convenzionale.

La transizione tra le modalità di volo elicottero e autogiro sarebbe avvenuta intorno ai 60 mph, (altre fonti affermano che ciò sarebbe avvenuto intorno ai 110 nodi); la transizione sarebbe stata compiuta spegnendo i getti alle estremità delle pale. Durante il volo autogiro, fino alla metà della portanza aerodinamica del velivolo era fornita dalle ali, che gli consentivano anche di raggiungere velocità più elevate.

Specifiche (Rotodyne "Y")

Caratteristiche generali:

- Equipaggio: due

- Capacità: 40-48 passeggeri

- Lunghezza: 58 piedi 8 pollici (17,88 m) di fusoliera

- Apertura alare: ali fisse da 46 piedi e 6 pollici (14,17 m)

- Altezza: 22 piedi 2 pollici (6,76 m) alla sommità del pilone del rotore

- Superficie alare: 475 piedi quadrati (44,1 m2 )

- Profilo alare : NACA 23015

- Peso a vuoto: 22.000 lb (9.979 kg)

- Peso lordo: 33.000 lb (14.969 kg)

- Capacità carburante: 7.500 lb (3.402 kg)

- Motopropulsore: 2 × Napier Eland N.El.7 turboelica da 2.800 cavalli (2.100 kW) ciascuno

- Motopropulsore: 4 × getto di punta del rotore, 1.000 lbf (4,4 kN) di spinta ciascuno

- Diametro rotore principale: 90 ft 0 in (27,43 m)

- Area del rotore principale: 591,0 m2 (6.362 piedi quadrati) Profilo alare del rotore: NACA 0015

- Velocità della punta della lama: 720 ft / s (219 m / s)

- Caricamento del disco : 6,14 lb / ft 2 (30 kg / m 2 )

- Eliche: 4 pale, diametro 4,0 m.

Prestazioni:

- Velocità massima: 190,9 mph (307,2 km / h, 165,9 kn) record di velocità

- Velocità di crociera: 185 mph (298 km / h, 161 kn)

- Intervallo: 450 mi (720 km, 390 nmi)

- Tangenza operativa: 13.000 piedi (4.000 m).

ENGLISH

The Fairey Rotodyne was a 1950s British compound gyroplane designed and built by Fairey Aviation and intended for commercial and military uses. A development of the earlier Gyrodyne, which had established a world helicopter speed record, the Rotodyne featured a tip-jet-powered rotor that burned a mixture of fuel and compressed air bled from two wing-mounted Napier Eland turboprops. The rotor was driven for vertical takeoffs, landings and hovering, as well as low-speed translational flight, but autorotated during cruise flight with all engine power applied to two propellers.

One prototype was built. Although the Rotodyne was promising in concept and successful in trials, the programme was eventually cancelled. The termination has been attributed to the type failing to attract any commercial orders; this was in part due to concerns over the high levels of rotor tip jet noise generated in flight. Politics had also played a role in the lack of orders (the project was government funded) which ultimately doomed the project.

Development

Background

From the late 1930s onwards, considerable progress was made on an entirely new field of aeronautics in the form of rotary-wing aircraft. While some progress in Britain had been made prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, wartime priorities placed upon the aviation industry meant that British programmes to develop rotorcraft and helicopters were marginalised at best. In the immediate post-war climate, the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Navy elected to procure American-developed helicopters in the form of the Sikorsky R-4 and Sikorsky R-6, known locally as the Hoverfly I and Hoverfly II respectively. Experience from the operation of these rotorcraft, along with the extensive examination that was conducted upon captured German helicopter prototypes, stimulated considerable interest within the armed services and industry alike in developing Britain's own advanced rotorcraft.

Fairey Aviation was one such company that was intrigued by the potential of rotary-wing aircraft, and proceeded to develop the Fairey FB-1 Gyrodyne in accordance with Specification E.16/47. The Gyrodyne was a unique aircraft in its own right that defined a third type of rotorcraft, including autogyro and helicopter. Having little in common with the later Rotodyne, it was characterised by its inventor, Dr JAJ Bennett, formerly chief technical officer of the pre-Second World War Cierva Autogiro Company as an intermediate aircraft designed to combine the safety and simplicity of the autogyro with hovering performance. Its rotor was driven in all phases of flight with collective pitch being an automatic function of shaft torque, with a side-mounted propeller providing both thrust for forward flight and rotor torque correction. On 28 June 1948, the FB-1 proved its potential during test flights when it achieved a world airspeed record, having attaining a recorded speed of 124.3 mph (200.0 km/h). The programme was not trouble-free however, a fatal accident involving one of the prototypes occurring in April 1949 due to poor machining of a rotor blade flapping link retaining nut. The second FB-1 was modified to investigate a tip-jet driven rotor with propulsion provided by propellers mounted at the tip of each stub wing, being renamed the Jet Gyrodyne.

During 1951 and 1952, British European Airways (BEA) internally formulated is own requirement for a passenger-carrying rotorcraft, commonly referred to the Bealine-Bus or BEA Bus. This was to be a multi-engined rotorcraft capable of serving as a short-haul airliner, BEA envisioned the type as being typically flown between major cities and carrying a minimum of 30 passengers in order to be economical; keen to support the initiative, the Ministry of Supply proceeded to sponsor a series of design studies to be conducted in support of the BEA requirement. Both civil and government bodies had predicted the requirement for such rotorcraft, and viewed it as being only a matter of time before they would become commonplace in Britain's transport network.

The BEA Bus requirement was met with a variety of futuristic proposals; both practical and seemingly impractical submissions were made by a number of manufacturers. Amongst these, Fairey had also chosen to submit its designs and to participate to meet the requirement; according to aviation author Derek Wood: "one design, particularly, seemed to show promise and this was the Fairey Rotordyne". Fairey had produced multiple arrangements and configurations for the aircraft, typically varying in the powerplants used and the internal capacity; the firm made its first submission to the Ministry on 26 January 1949. Within two months, Fairey had produced a further three alternative submissions, centring on the use of engines such as the Rolls-Royce Dart and Armstrong Siddeley Mamba. In October 1950, an initial contract for the development of a 16,000 lb, four-bladed rotorcraft was awarded. The Fairey design, which was considerably revised over the years, received government funding to support its development.

Early on in development, Fairey found that securing access to engines to power its design proved to be difficult. In November 1950, Rolls-Royce chairman Lord Hives protested that the design resources of his company were being stretched too thinly across multiple projects; accordingly, the initially-selected Dart engine was switched to the Mamba engine of rival firm Armstrong Siddeley. By July 1951, Fairey had re-submitted proposals using the Mamba engine in two and three-engine layouts, supporting all-up weights of 20,000 lb (9.1 t) and 30,000 lb (14 t) respectively; the adopted configuration of pairing the Mamba engine to auxiliary compressors was known as the Cobra. Due to complaints by Armstrong Siddeley that it too was lacking resources, Fairey also proposed the alternative use of engines such as the de Havilland Goblin and the Rolls-Royce Derwent turbojet to drive the forward propellers.

Fairey did not enjoy a positive relationship with de Havilland however, and thus chose to turn to D. Napier & Son and its Eland turboshaft engine in April 1953. Following the selection of the Eland, the basic design of the rotorcraft, known as the Rotodyne Y, soon emerged; it was powered by a pair of Eland N.El.3 engines furnished with auxiliary compressors and a large-section four-blade main rotor, with a projected all-up weight of 33,000 lb. At the same time, a projected enlarged version, designated as the Rotodyne Z, outfitted with more powerful Eland N.El.7 engines and an all-up weight of 39,000 lb, was proposed as well.

Contract

In April 1953, the Ministry of Supply contracted for the building of a single prototype of the Rotodyne Y, powered by the Eland engine, later designated with the serial number XE521, for research purposes. As contracted, the Rotodyne would have been the largest transport helicopter of its day, seating a maximum of 40 to 50 passengers, while possessing a cruise speed of 150 mph and a range of 250 nautical miles. At the time of the award, Fairey had estimated that £710,000 would cover the costs of producing the airframe. With a view to an aircraft that would meet regulatory approval in the shortest time, Fairey's designers worked to meet the Civil Airworthiness Requirements for both helicopters and similar-sized twin-engined aircraft. A one-sixth scale rotorless model was extensively wind tunnel tested for fixed-wing performance. A smaller (1/15th-scale) model with a powered rotor was used for downwash investigations.

While the prototype was being built, funding for the programme reached a crisis. Cuts in defence spending led the Ministry of Defence to withdraw its support, pushing the burden of the costs onto any possible civilian customer. The government agreed to maintain funding for the project only if, among other qualifications, Fairey and Napier (through their parent English Electric) contributed to development costs of the Rotodyne and the Eland engine respectively. As a result of disagreements with Fairey on matters of policy, Dr Bennett left the firm to join Hiller Helicopters in California; responsibility for the Rotodyne's development was assumed by Dr George S Hislop, who became the firm's chief engineer.

The manufacturing of the prototype's fuselage, wings, and rotor assembly was conducted at Fairey's facility in Hayes, Hillingdon, West London, while construction of the tail assembly was performed at the firm's factory in Stockport, Greater Manchester and final assembly was performed at White Waltham Airfield, Maidenhead. In addition, a full-scale static test rig was produced at RAF Boscombe Down to support the programme; the static rig featured a fully operational rotor and powerplant arrangement which was demonstrated on multiple occasions, including a 25-hour approval testing for the Ministry.

While construction of the first prototype was underway, prospects for the Rotodyne appeared positive; according to Wood, there was interest in the type from both civil and military quarters. BEA was monitoring the progress of the programme with interest; it was outwardly expected that the airline would place an order shortly after the issuing of an order for a militarised version of the rotorcraft. The American company Kaman Helicopters also showed strong interest in the project, and was known to have studied it closely as the firm considered the potential for licensed production of the Rotodyne for both civil and military customers.

Due to army and RAF interest, development of the Rotodyne had been funded out of the defence budget for a time. During 1956, the Defence Research Policy Committee had declared that there was no military interest in the type, which quickly led to the Rotodyne becoming solely reliant upon civil budgets as a research/civil prototype aircraft instead. After a series of political arguments, proposals, and bargaining; in December 1956, HM Treasury authorised work on both the Rotodyne and Eland engine to be continued until the end of September 1957. Amongst the demands exerted by the Treasury were that the aircraft had to be both a technical success and would need to acquire a firm order from BEA; both Fairey and English Electric (Napier's parent company) also had to take on a portion of the costs for its development as well.

Testing and evaluation

On 6 November 1957, the prototype performed its maiden flight, piloted by chief helicopter test pilot Squadron Leader W. Ron Gellatly and assistant chief helicopter test pilot Lieutenant Commander John G.P. Morton as second pilot. The first flight had originally been projected to take place in 1956; however, delay was viewed as inevitable with an entirely new concept such as used by the Rotodyne.

On 10 April 1958, the Rotodyne achieved its first successful transition from vertical to horizontal and then back into vertical flight. On 5 January 1959, the Rotodyne set a world speed record in the convertiplane category, at 190.9 mph (307.2 km/h), over a 60-mile (100 km) closed circuit. As well as being fast, the rotorcraft had a safety feature: it could hover with one engine shut down with its propeller feathered, and the prototype demonstrated several landings as an autogyro. The prototype was demonstrated several times at the Farnborough and Paris air shows, regularly amazing onlookers. In one instance, it even lifted a 100 ft girder bridge.

The Rotodyne's tip drive and unloaded rotor made its performance far better when compared to pure helicopters and other forms of "convertiplanes." The aircraft could be flown at 175 kn (324 km/h) and pulled into a steep climbing turn without demonstrating any adverse handling characteristics.

Throughout the world, interest was growing in the prospect of direct city-to-city transport. The market for the Rotodyne was that of a medium-haul "flying bus": It would take off vertically from an inner-city heliport, with all lift coming from the tip-jet driven rotor, and then would increase airspeed, eventually with all power from the engines being transferred to the propellers with the rotor autorotating. In this mode, the collective pitch, and hence drag, of the rotor could be reduced, as the wings would be taking as much as half of the craft's weight. The Rotodyne would then cruise at speeds of about 150 kn (280 km/h) to another city, e.g., London to Paris, where the rotor tip-jet system would be restarted for landing vertically in the city centre. When the Rotodyne landed and the rotor stopped moving, its blades drooped downward from the hub. To avoid striking the vertical stabilisers on startup, the tips of these fins were angled down to the horizontal. They were raised once the rotor had spun up.

By January 1959, British European Airways (BEA) announced that it was interested in the purchase of six aircraft, with a possibility of up to 20, and had issued a letter of intent stating such, on the condition that all requirements, including noise levels, were met. The Royal Air Force (RAF) had also placed an order for 12 military transport versions. New York Airways signed a letter of intent for the purchase of five at $2m each, with an option of 15 more albeit with qualifications, after calculating that a larger Rotodyne could operate at half the seat mile cost of helicopters; however, unit costs were deemed too high for very short hauls of 10 to 50 miles, and the Civil Aeronautics Board was opposed to rotorcraft competing with fixed-wing on longer routes. Japan Air Lines, which had sent a team to Britain to evaluate the Rotodyne prototype, stated it would experiment with Rotodyne between Tokyo Airport and the city itself, and was interested in using it on the Tokyo-Osaka route as well.

According to rumours, the U.S. Army was also interested in buying around 200 Rotodynes. Fairey was keen to secure funding from the American Mutual Aid programme, but could not persuade the RAF to order the minimum necessary 25 rotorcraft needed; at one point, the firm even considered providing a single Rotodyne to Eastern Airlines via Kaman Helicopters, Fairey's U.S. licensee, so that it could be hired out to the U.S. Army for trials. All Rotodynes destined for US customers were to have been manufactured by Kaman in Bloomfield, Connecticut.

Financing from the government had been secured again on the proviso that firm orders would be gained from BEA. The civilian orders were dependent on the noise issues being satisfactorily met; the importance of this factor had led to Fairey developing 40 different noise suppressors by 1955. In December 1955, Dr Hislop said he was certain that the noise issue could be 'eliminated'. According to Wood, the two most serious problems revealed with the Rotodyne during flight testing was the noise issue and the weight of the rotor system, the latter being 2,233 lb above the original projection of 3,270 lb.

Issues and cancellation

In 1959, the British government, seeking to cut costs, decreed that the number of aircraft firms should be lowered and set forth its expectations for mergers in airframe and aero-engine companies. By delaying or withholding access to defence contracts, the British firms could be forced into mergers; Duncan Sandys, Minister of Aviation, expressed this policy to Fairey and made it known that the price of continued government backing for the Rotodyne would be for Fairey to virtually withdraw from all other initiatives in the aviation field. Ultimately, Saunders-Roe and the helicopter division of Bristol were incorporated with Westland; in May 1960, Fairey Aviation was also taken over by Westland. By this time, the Rotodyne had flown almost 1,000 people for 120 hours in 350 flights and conducted a total of 230 transitions between helicopter and autogiro — with no accidents.

By 1958, the Treasury was already expressing its opposition to further financing for the programme. The matter was escalated to Harold Macmillan, the then Prime Minister, who wrote to Aubrey Jones, the Minister of Supply, on 6 June 1958, stating that "this project must not be allowed to die". Considerable importance was placed upon BEA supporting the Rotodyne by issuing and order; however, the airline refused to procure the aircraft until it was satisfied that guarantees were given over its performance, economy, and noise criteria. Shortly after Fairey's merger with Westland, the latter was issued with a £4 million development contract for the Rotodyne, which was intended to see the type enter service with BEA as a result.

As flight testing with the Rotodyne prototype had proceeded, Fairey had become increasingly dissatisfied with Napier and the Eland engine as progress to improve the latter had been less than expected. For the extended 48-seat model of the Rotodyne to be achieved, the uprated 3,500 ehp Eland N.E1.7 would be necessary; of the estimated £7 million needed to produce the larger aircraft, £3 million would be for its engines. BEA was particularly supportive of a larger aircraft, potentially seating as many as 66 passengers, which would have required a still-far greater sum of money to achieve. Fairey was already struggling to achieve the stated performance of the Eland engine and had resorted to adopting a richer fuel mixture to get the necessary power, a side effect of which was to further aggravate the noticeable noise issue as well as reducing fuel efficiency. As a result of being unable to resolve the issues with the Eland, Fairey opted to adopt the rival Rolls-Royce Tyne turboprop engine to power the larger Rotodyne Z instead.

The larger Rotodyne Z design could be developed to take 57 to 75 passengers and, when equipped with the Tyne engines (5,250 shp/3,910 kW), would have a projected cruising speed of 200 kn (370 km/h). It would be able to carry nearly 8 tons (7 tonnes) of freight; cargoes could have included some British Army vehicles and even the intact fuselage of some fighter aircraft that would fit into its fuselage. It would have also been able to carry large cargoes externally as an aerial crane, including vehicles and whole aircraft. According to some of the later proposals, the Rotodyne Z would have had a gross weight of 58,500 lb, an extended rotor diameter of 109 ft, and a tapered wing with a span of 75 ft.

However, the Tyne engines were also starting to appear under-powered for the larger design. The Ministry of Supply had pledged to finance 50 per cent of the development costs for both the Rotodyne Z and for the model of the Tyne engine to power it. Despite the strenuous efforts of Fairey to achieve its support, the expected order from the RAF did not materialise — at the time, the service had no particular interest in the design, being more focused on effectively addressing the issue of nuclear deterrence. As the trials continued, both the associated costs and the weight of the Rotodyne continued to climb; the noise issue continued to persist, although, according to Wood: "there were signs that silencers would later reduce it to an acceptable level".

While the costs of development were shared half-and-half between Westland and the government, the firm determined that it would still need to contribute a further £9 million in order to complete development and achieve production-ready status. Following the issuing of a requested quotation to the British government for 18 production Rotodynes, 12 for the RAF and 6 for BEA, the government responded that no further support would be issued for the project due to economic reasons. Accordingly, on 26 February 1962, official funding for the Rotodyne was terminated in early 1962. The project's final end came when BEA chose to decline placing its own order for the Rotodyne, principally due to its concerns regarding the high-profile tip-jet noise issue. The corporate management at Westland determined that further development of the Rotodyne towards production status would not be worth the investment required. Thus ended all work on the world's first vertical take-off military/civil transport rotorcraft.

After the programme was terminated, the prototype Rotodyne itself, which was government property, was dismantled and largely destroyed in a fashion reminiscent of the Bristol Brabazon. A single fuselage bay, as pictured, plus rotors and rotorhead mast survived, and are on display at The Helicopter Museum, Weston-super-Mare.

Analysis

The one great criticism of the Rotodyne was the noise the tip jets made; however, the jets were only run at full power for a matter of minutes during departure and landing and, indeed, the test pilot Ron Gellatly made two flights over central London and several landings and departures at Battersea Heliport with no complaints being registered, though John Farley, chief test pilot of the Hawker Siddeley Harrier later commented:

From two miles away it would stop a conversation. I mean, the noise of those little jets on the tips of the rotor was just indescribable. So what have we got? The noisiest hovering vehicle the world has yet come up with and you're going to stick it in the middle of a city?

There had been a noise-reduction programme in process which had managed to reduce the noise level from 113 dB to the desired level of 96 dB from 600 ft (180 m) away, less than the noise made by a London Underground train, and at the time of cancellation, silencers were under development, which would have reduced the noise even further — with 95 dB at 200 ft "foreseen", the limitation being the noise created by the rotor itself. This effort, however, was insufficient for BEA which, as expressed by Chairman Sholto Douglas, "would not purchase an aircraft that could not be operated due to noise", and the airline refused to order the Rotodyne, which in turn led to the collapse of the project.

It is only relatively recently that interest has been reestablished in direct city-to-city transport, with aircraft such as the AgustaWestland AW609 and the CarterCopter/PAV. The 2010 Eurocopter X3 experimental helicopter shares the general configuration of the Rotodyne, but is much smaller. A number of innovative gyrodyne designs are still being considered for future development.

Design

The Fairey Rotodyne was a large hybrid rotorcraft, known as a compound gyroplane or Gyrodyne. According to Wood, it was "the largest transport helicopter of its day". It featured an unobstructed rectangular fuselage, capable of seating between 40 and 50 passengers; a pair of double-clamshell doors were placed to the rear of the main cabin so that freight and even vehicles could be loaded and unloaded.

The Rotodyne had a large, four-bladed rotor and two Napier Eland N.E.L.3 turboprops, one mounted under each of the fixed wings. The rotor blades were a symmetrical aerofoil around a load-bearing spar. The aerofoil was made of steel and light alloy because of centre of gravity concerns. Equally, the spar was formed from a thick machined steel block to the fore and a lighter thinner section formed from folded and riveted steel to the rear. The compressed air was channelled through three steel tubes within the blade. The tip-jet combustion chambers were composed of Nimonic 80, complete with liners that were made from Nimonic 75.

For takeoff and landing, the rotor was driven by tip-jets. The air was produced by compressors driven through a clutch off the main engines. This was fed through ducting in the leading edge of the wings and up to the rotor head. Each engine supplied air for a pair of opposite rotors; the compressed air was mixed with fuel and burned. As a torqueless rotor system, no anti-torque correction system was required, though propeller pitch was controlled by the rudder pedals for low-speed yaw control. The propellers provided thrust for translational flight while the rotor autorotated. The cockpit controls included a cyclic and collective pitch lever, as in a conventional helicopter.

The transition between helicopter and autogyro modes of flight would have taken place around 60 mph, (other sources state that this would have occurred around 110 knots); the transition would have been accomplished by extinguishing the tip-jets. During autogyro flight, up to half of the rotocraft's aerodynamic lift was provided by the wings, which also enabled it to attain higher speed.

(Web, Google, Wikipedia, You Tube)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento

Nota. Solo i membri di questo blog possono postare un commento.